1. Introduction

The territorial decentralization process, within the context of the Spanish Transition and initiated following the death of the dictator Francisco Franco, holds a special place for what came to be known as the “Basque problem”. How to fit the question of Euskadi into the complex structure of regional autonomy turned into, as Eduardo Álvarez Bragado put it (2017:1), “one of the great headaches for successive Spanish governments”. The main difficulty for the solution of the problem was the existence of the ETA terrorist group, whose activities continued for over thirty years, leaving over eight hundred dead, and imposing a practically suffocating air of intimidation in the region (Avilés, 2010).

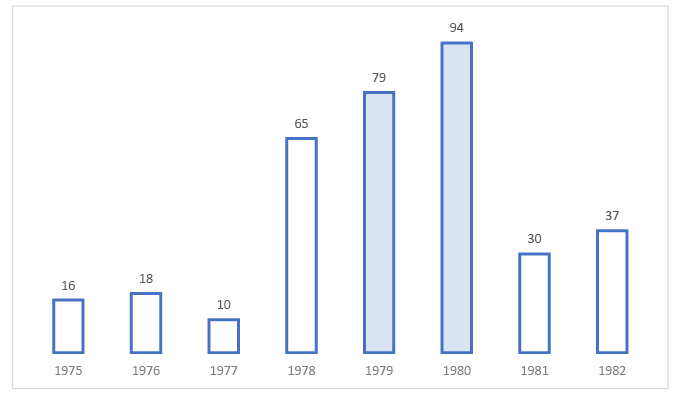

As Martín Villa recalls (1984: 175), the terrorist phenomenon is key to understanding the direction the Basque Country took on its journey to autonomy. “A set of circumstances which have still not been properly studied meant that the nationalist revindication was not in the hands of the PNV, but in those of a terrorist group, ETA, and that, consequently, did not follow the norms of political opposition, but those of violence”. Furthermore, there was the mistaken idea that, with Franco dead and the beginnings of democracy, terrorist activities would disappear (Preston, 1986), not only did that not happen, but the opposite came to pass, as seen in the figures of deaths in Graph 1.

Graph 1: ETA killings (1975-1982)

Source: created by the author from De la Calle & Sánchez Cuenca (2004)

As seen here, the period of greatest ETA violence came between 1979 and 1980, with 173 deaths. Florencio Domínguez’s work, Vidas rotas: La historia de los hombres, las mujeres y los niños víctimas de ETA (Broken Lives: the story of the men, women and children who fell victim to ETA) (2010), gives a rough idea of the tension in Spanish society with a detailed analysis of the attacks carried out by the terrorist group. While it is true that this organization did not have a monopoly on violence during La Transición, which historians no longer refer to as “peaceful” (Baby, 2018), the terror caused by the actions of Euskadi Ta Askatasuna are unrivalled by other groups or factions during the transitional period.

In this context, it is hardly surprising that the terrorist question was a clear factor of instability and uneasiness for Spanish citizens. A brief glance at the findings of the Centre for Sociological Research (CIS) confirms this. When asked in successive opinion polls in 1979 and 1980 about their greatest day-to-day concerns, Spaniards consistently named terrorism, along with the economy and unemployment, as among their greatest worries.1 It is interesting then, to consider the role played by the mass media and in particular that of television in informing the audience about such a delicate matter, something which has provoked profound debate amongst journalists themselves.

Any consideration of the fundamental elements which fostered the creation of an atmosphere which facilitated the change to democracy sees the daily papers, magazines, radio stations and, above all, state television, take pride of place on the list (Silva, 1986). Similarly, the number of authors who have described the media as both a substantial and energizing element in the emergence of the new regime is noteworthy (Redero San Román & García González, 1992; Barrera, 1997; Zugasti, 2008). The same is true of television, seen as an indispensable tool for orchestrating reform and introducing a “unique model of Transición” headed by the Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez (Martín Jiménez, 2013: 45).

However, the intersection between ETA terrorism and the role of the mass media during the transition to democracy, contains a less than prolific, though highly interesting, field of study. The representation of ETA terrorism in the national (Martínez Setién, 1994), regional (Armentia & Caminos, 2012), and European press (Díaz, 2009), as well as on television (Sánchez García, Rueda Laffond & Coronado, 2009; Martín Jiménez, 2011; De Pablo, Mota & López, 2019), awaits new perspectives. The aforementioned Virginia Martín Jiménez affirms in “Terrorismo etarra y televisión: TVE como agente conformador de una imagen pacífica de la transición (1976-1978)” (“ETA Terrorism and TV: TVE as a moulding agent of a peaceful image of the transition”) (2011) that the information provided by Televisión Española concerning terrorism during the phase of consensus was intended to shape public opinion such that it did not compromise the transformation that was taking place in Spanish society:

Televisión Española carried out a considered media policy when facing terrorism at such a delicate time as the Transición (…) This strategy mitigated the provocation of the social effects sought by the fanatics. Instead of producing an authoritarian response or a generalized confrontation, the strategy favoured state television moulding public opinion to reject violence and continuing down the path of political reform. (Martín Jiménez, 2011: 79)

Although one might coincide with the author’s arguments, it is pertinent to note the changes in the tendency after the end of the pre-constitutional stage, and the beginning of a new panorama marked by instability and the constant threat to the survival of political freedom (De Andrés, 2002). The turbulence that characterized the period from 1979 to the key date of February 23, 1981 –partly a result of the feedback between a coup d’état mentality and terrorism (Muñoz Alonso, 1986)–, together with a growing “disenchantment” as the defining sentiment of that time, requires an analysis of the reporting of ETA’s activities on the small screen at an especially tough time when “successive attacks put the whole democratic process and the very existence of the rule of law against the ropes” (Garrido, 2013: 122).

From this starting point, this study has two goals. The first is to study the reverberations of ETA violence on Televisión Española during these so-called “years of lead” (1979-1980). The second is to analyse the audio-visual media strategy of the government’s anti-terrorism policy through the television, a key medium for the Suarist administration, and, on numerous occasions, a transmission belt of the interests of the executive. It is worth remembering that at that time, TVE was the most important audio-visual company in Spain and had the greatest audience reach, as well as being an element of conflict used by the party in power and by the opposing forces as an instrument of opposition (Herrero, 2020). “To understand what happens on Televisión”, remarked Juan Felipe Vila-San Juan (1981: 18), “you have to look at what’s behind, the reasons and motives that drive events”. Furthermore, says the same author, what is “behind” (always) has to do with politics. “Ortega’s ‘I am myself, and my circumstances’ could never be better applied than in the case of Televisión Española. TVE is the ‘I’ and the ‘circumstances’ are politics”, which justifies the two objectives of this paper.

2. Methodology

The main sources of this study are the archives of the four daily papers that can be taken as the references in the written press during the Transición, namely: El País, ABC, La Vanguardia and Diario 16.2 These four newspapers occupied the podium of journalism of the time and dedicated a page every day to informing their readers of the content broadcast by Televisión Española. Although this method may appear surprising (using one medium to study another), the press provide enormously useful material for research of this nature. The newspapers of the time represent “the most reliable reference for what was happening in the public sphere as opposed to the State channels of communication” (Redero & García, 1992: 90), that is: TVE, Radio Nacional, the Francoist press, etc.

These daily pages about programmes are basic to knowing what was on and registered the time and date of certain broadcasts. Many news items, editorials and opinion columns focused on the public channel, its programmes and how it covered stories. Therefore, a review of these pages can give us a considerable corpus of study which in this case is made up of all the items published that deal with news and programmes dedicated directly or tangentially to the ETA terrorist group. A total of 102 news items have been selected. The corpus analysed is composed of the following sections:

- Variables for the classification of the news items: type of news (report, interview, editorial, opinion piece, letter to the editor), publication date, title, author, page number, section/position, image (where applicable), quotes, observations (where applicable).

- Variables for the classification of the TV programme cited in the news item: title, channel (TVE 1 or 2), time and date of broadcast, genre (news, education, entertainment), frequency (daily, weekly, monthly, special) protagonism of terrorism within the programme (principal/monographic or secondary), description of the programme’s content.

Other sources employed for this research include the weekly magazine edited by RTVE itself, Tele – Radio, and the digital archive of the Congress, whose documents reflect the fact that news coverage by the public medium relative to ETA had a direct part to play in parliamentary debate. In line with the objectives of this paper, the programmes of greatest interest were news programmes, both daily (Telediarios, Specials), and weekly (Informe Semanal, Siete Días, Primera Página, Parlamento etc.) and broadcast on TVE 1 or 2. However, as our intention is to offer the broadest and most detailed vision possible, we also considered debate programmes (La Clave, Revista de Prensa) or even cultural shows (Encuentros con las letras) which dealt with the same matter.

Concerning the period of study, the introductory paragraph explained the reasons for the chronological limits to this paper. The spiral of terrorist violence (173 deaths in barely two years; an average of a killing every four days), together with a tense social climate flooding the streets of the Basque Country and the rest of the nation until the attempted Coup d’État on February 23 (23-F), means that these twenty-four months were sufficiently intense to merit their specific analysis. It should not be forgotten that in October 1979 a referendum was held on the Statute of Autonomy for Euskadi; a historic event that marked the passage of Basque reality over the following months. Another major event also took place: the first election to the autonomous parliament. (March 1980).

As regards research hypothesis, our first premise is that Televisión Española habitually reported on terrorist attacks by Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) but tried to lessen any impact that could jeopardise the stability of the Government, the viability of Basque autonomy and Spanish democracy in general. At the same time, we postulate that the decay in Adolfo Suárez’s public image in his last two years as Prime Minister (Contreras, 2016) was affected by public perception, via television, of the UCD’s anti-terrorism policy and of Suarez’s own attitude to the Basque problem.

3. Between silence and information. Dilemmas in the fight against ETA and the difficulties of the media in transition

On May 25, 1979, Lieutenant General Luis Gómez Hortigüela left his home to head off for work in an official car accompanied by his chauffer and two colonels, Jesús Ábalos Giménez and Agustín Laso Corral. Around nine fifteen that morning, an ETA commando, armed with submachine guns and hand grenades, attacked the vehicle and killed its four occupants. Negotiations for the drawing up of the Guernica Statutes had recently started and Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez was due in only five days’ time to address Parliament and make an institutional declaration against terrorism. Rumours were rife that he would appear on TVE to pour oil on the waters, an event that never came to pass. Months later, the journalist Pilar Urbano recalled the episode thus:

I remember being on the plane that took us to Sevilla for Armed Forces’ Day and that we pressed him to “speak on TV”. But he said “no”, that he couldn’t lie to the people telling them that terrorism was going to disappear, because who could guarantee to him that another packet of ‘goma-2’ wasn’t going to go off 15 minutes later (Urbano, 1979)

This dilemma of informing or not informing about terrorism, or between “speaking or not speaking” on television, in the words of Urbano, was one of the great quandaries facing TVE and the centrist Government. As Virginia Martín put it (2011: 68), the television strategy of the early years of the Transición would be “closely tied to the government’s strategy”, which took a middle route between informing and a “media blackout”. The objective of this latter option was to break with the “terrorist ritual”. A ritual that took place when violent acts reached a wide audience through the media (Jenkins, 1984; Picard, 1993; Laqueur, 1997; Papacharissi & Oliveira, 2008; Sánchez Duarte, 2009). According to Eduardo Sotillos, a TV professional of the time, interviewed by the same author:

We tried to act prudently; there were moments when, due to the seriousness, there was a sense of commitment amongst us, the journalists, to not put democracy at risk. We couldn’t transmit the feeling that the country was falling to pieces. I must say that we weighed our words carefully due to that prudence and the sense of shared commitment we were working with. Both the journalists and the politicians felt the same. (Martín Jiménez, 2011: 68)

Shortly before the attack on General Gómez Hortigüela, omitted from one of the most prestigious current affairs programmes of the weekend, Informe Semanal3, journalist Carlos Arauz questioned the “policy of silence” as a formula for combatting terrorism and called for the media to “condemn with increasing vigour, to create awareness and, if necessary, try more striking and dissuasive methods” (Arauz, 1979). El País also denounced “the fallacy of the disinformation thesis”, recommending “the broadest possible information” in the face of terrorism, providing this does not interfere with law enforcement (El País, 1979a). The first text was published after the demonstration of April 8 in Bilbao in response to the killing of three National Police officers in San Sebastián. The march was called by all the Basque political forces with the exception of the Unión de Centro Democrático. During the demonstration, followers of Herri Batasuna chanted in favour of ETA, according to El País. This fact was deliberately silenced by the Sunday news reports on both Radio and Televisión Española, according to the same article (El País, 1979b).

Months later, with reference to the death of activist Gladys del Estal by police bullets and the kidnapping by ETA of the Government delegate in Navarra for Industry and Energy, Ignacio Astiz, the Grupo Comunista criticized the “deformed version of events” proffered by Televisión Española (BOCG, F-0074-II, 1979). To the question of informing or not informing was now added the “how” and the “why” to inform in a particular way. The explanation is simple: the new constitutional phase and the plan to grant RTVE its own legal Statute opened the door to the existence of mechanisms to control the public medium. Complaints such as those of the Grupo Comunista served to denounce the way in which TVE was presenting matters and the channel’s possible party bias.

Regarding the above, a further episode occurred in August 1979, only days after the publication of the report on the projected Statute of Autonomy for the Basque Country. Carlos Garaicoechea, later to be the first Lendakari, spoke to the US newspaper, The New York Times, after publication of the report. It was the first of the month when the President of the Basque General Council mentioned to the press the need to concede a new amnesty, in declarations later clarified by Garaicoechea himself (El País, 1979c). For their part, ETA-pm would state in a clandestine press conference, that they had held negotiations with the Government about removing the police from Soria prison and transferring several prisoners to Euskadi. In exchange, a halt to attacks on Mediterranean beaches was agreed. Another attack in the nation’s capital took place on that same August first in response to the non-fulfilment of part of this secret pact between ETA and the Government, according to the terrorists’ version of events. The UCD government immediately denied this. And several dailies such as El País and ABC recognised they were surprised by the speed of the reaction of the State media, such as TVE, in issuing these denials (ABC, 1979).

Several months later, in a Basque Country now constituted as an Autonomous Region and with its own duly elected Parliament, the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV) would point to another controversial use of the small screen. It was November 1980; a little after ETA had killed a member of the Executive Council of the UCD in Guipúzcoa, Juan de Dios Doval. The death of a member of the centrist grouping set off another wave of friction in the region, as well as mass demonstrations that, in this case, and despite the disturbances,4 received “excellent news coverage” on TVE (El País, 1980), and led to an exchange between the Suárez Cabinet and the PNV due to the creation of the so-called “Peace Front”. This agreement was subscribed to by the Unión de Centro Democrático (UCD), Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV), Partido Carlista (EKA), Partido Socialista de Euskadi (PSE-PSOE) and the Partido Comunista de Euskadi (EPK). It was intended to be a mechanism to continue the campaign to heighten awareness and to mobilise all sectors of Basque society towards peace and the rejection of violence.

Come November 21, the executive organ of the PNV, the Euskadi Buru Batzar (EBB), withdrew from the pact, considering that the Government was obstructing the proper application of the Statute of Autonomy. The EBB also indicated that if some sectors of the Basque people supported violence and terrorism, this was because they were frustrated by “neither seeing nor believing in the instauration of autonomy” (Diario 16, 1980). Just twenty-four hours later, the Government would respond with regrets about the “intolerable political justification of ETA’s terrorist acts” in a Basque Country where law and self-governance were applied “with the greatest vigour” (Diario 16, 1980a). The culmination of all this was to come with the counter-reply by the nationalist grouping on Sunday, November 23. This came in a note denouncing RTVE’s partiality in having only given one side of the story:

We find it absolutely intolerable, especially as emphasized by the Government’s note in saying that “public opinion has to value (our note) for its true worth”, that the Government has read out their whole note, with reiteration and emphasis, on the radio and television, without our note having been previously made public by the same means. This happened in Franco’s times, and it is clear in which school some learnt the way in which public opinion can evaluate certain situations for their true worth. (ABC, 1980)

The above lines form part of the habitual rhetoric of the opposition parties (both national and regional) as regards the partisan use of a medium that at that time was going through its own transition (Bustamante, 2013). The political battle about the democratization of the state channel added further difficulty to the already complex task of reporting on the attacks. TVE’s coverage of terrorism was complicated by the supposed subordination of the channel to the objectives of the UCD. However, analysis of the programming shows that the public medium did cover the subject frequently, even creating a sensation of news “overabundance”5 which contributed to normalizing the attacks (ABC, 1980a). For Carlos Arauz, an ABC journalist:

Until recently television would strive to cloak the news regarding terrorism so that the public didn’t get alarmed, or so that the public kept faith in those who were governing, but not now. Now. (…) television, clearly as a spokesman for the Government, intends to highlight terrorist deaths so that the previously uninformed citizens take the initiative. But they’re finding that the people don’t react (…) that indifference has enslaved the body social. (Arauz, 1979a)

Along the same lines, specific or monothematic programmes speak of television’s interest in presenting a subject to the audience that could not be seen as just an anecdote, given the continual succession of killings. The outstanding example is Fernando Ónega’s programme, Revista de prensa, which gathered the editors of the biggest newspapers of the time to discuss how journalists should report on terrorism (Diario 16, 1980b). The international viewpoint was another way of dealing with the question. This was the case of the aforementioned Informe Semanal and the current affairs programme Pantalla Abierta,6 that in July 1979 dedicated a report to terrorism in Italy. On other occasions, the audio-visual medium chose to cancel a pre-recorded programme or change their programming. This happened with an issue that El País transferred to Pantalla Abierta (El País, 1979d), based on far-right terrorism (which was never again considered). Something similar happened to an interview with a professor from the Universidad de Sevilla, Manuel Villar Raso, whose participation in Encuentros con las letras on November 20 was censored due to the subject matter of his book: terrorist commandos in the Basque Country (Table 1).

Table 1: Programmes about terrorism on Televisión Española (1979-1980)7

|

Name of the programme |

Channel |

Time & date of broadcast |

Category |

Content |

|

Pantalla abierta |

One |

27/7/1979 |

Current affairs |

Report on terrorism in Italy. |

|

21: 45 |

||||

|

Informe Semanal |

One |

29/12/1979 |

News |

Review of the decade. The generalization of terrorism around the world. |

|

20: 30 |

||||

|

Revista de prensa |

One |

01/07/1980 |

Debate |

ETA’s offensive on Spain’s beaches |

|

15: 45 |

||||

|

Primera Página |

One |

02/08/1980 |

News |

Terrorist acts over the 1970s (excepting those in Spain). |

|

21:30 |

||||

|

Revista de prensa |

One |

09/09/1980 |

Debate |

Keys to reporting on terrorism. |

|

20: 30 |

||||

|

Revista de prensa |

One |

11/11/1980 |

Debate |

The latest terrorist attacks. |

|

20: 30 |

||||

|

Encuentros con las letras (programme censored) |

Two |

20/11/1980 |

Interviews |

Interview of Manuel Villar Raso, professor in the Universidad de Sevilla, about his book Comandos vascos (1980), focused on terrorist violence. |

|

21:00 |

||||

|

Parlamento |

One |

22/11/1980 |

News |

Declarations by Juan José Rosón, Minister of the Interior, on Franco-Spanish cooperation in the fight against ETA. |

|

14: 00 |

Source: created by the author from the archives of El País, Diario 16, La Vanguardia, ABC & Tele-Radio

The examples on this list certify the existence of “selective treatment” (Rodrigo, 1991: 62) applied by Televisión Española based on the omission or broadcasting of certain events. The decision to take one route or another would depend on several reasons; from self-censorship by the journalists to motives directly related to politics, fruit of the “original sin” by which TVE was considered just another department of state bureaucracy. Although it is difficult to know the criteria used by managers when eliminating or prohibiting a programme, the contemporary press heard of the existence of the TVE Programmes Board: an entity with the mission of “orientating, advising and, especially, controlling the product programmed or broadcast” (Banegas, 2015: 475). With similar functions to the old Advisory Commissions, of which Adolfo Suárez had been the secretary in 1964, the Board of Televisión Española was composed of the channel’s most senior managers.8

In the case of the censored interview with Manuel Villar, the journalist José Ramón Pérez Ornia was to indicate: the broadcast was prohibited by the personal decision of Luis Ezcurra Carillo, sub-director of Radiodifusión & Televisión and, according to several authors, one of the most influential men in the organisation (Munsó, 2001; Morán, 2009). The procedure followed by Luis Ezcurra was to censor the programme basing himself on the ruling issued by the full Board on December 18, 1980 and appealing later to the State Attorney General for a possible justification of terrorism. Said ruling would have been drawn up by Luis Ezcurra himself, Juan Jesús Buhigas (assistant to the management of TVE for production and management of News Services) and Pablo Irazazábal (director of News Services). The article includes a literal reproduction of the act:

(…) The director of channel Two and the sub-director of TVE for documentaries were consulted. The former stated that he is laterally aware of the matter and had not received any denouncement of a possible justification of terrorism. The sub-director for documentaries similarly said that he could see nothing that would call for the suppression of the programme. That was all from the subdirector general’s report. Subsequently, the Fiscal General’s note was read out, which said that the programme should not be broadcast, as this would involve responsibility for a justification of terrorism. The note is in the possession of the Sub-Director General of RTVE. The Sub-Director General of RTVE spoke again to insist that it is always preferable, when in doubt, to withdraw a programme from broadcast, but that censorship should not take place. (Pérez Ornia, 1981)

It is important to remember that the management of Radiotelevisión Española was occupied between 1977 and 1981 by Fernando Arias Salgado, son of the former Minister for Information and Tourism under whom Televisión was inaugurated in Spain and brother of the deputy-Prime Minister (1980) and Minister of the Presidency (1980-1981), Rafael Arias Salgado. The head of TVE News Services was the previously mentioned Pablo Irazazábal, promoted by Adolfo Suárez during his time as Director General of the organization (1969-1973) (Moran, 2009: 447). Directing Revista de Prensa was the former press officer for the Suarist Cabinet, Fernando Ónega. All of them are examples of the undeniable linkage between politics and television.

Probably the best way to appreciate the difficulty of presenting the ETA labyrinth on TV screens is to consider all these political posts, the UCD’s media policy in the struggle against terrorism and the debates taking place in the parliamentary forum. The above paragraphs give us an idea of the manoeuvres designed to influence how terrorism was perceived by public opinion. The main complaints about the supposed spin or omission of facts and about the Government’s influence on TVE came precisely when there were peaks in the terrorist threat (with a special mention for those attacks involving members of the Armed Forces) or questions raised about the Executive’s handling of the situation (mass demonstrations, supposed secret negotiations ETA-UCD, etc.). The following section seeks to give a broader vision of this approach.

4. Public opinion of anti-terrorism policy. UCD, Suárez and trial by television

The distancing of Adolfo Suárez from political life had been a recurring theme since his investiture as Head of Government in March 1979. It came to be called “Moncloa syndrome” as a diagnosis of his withdrawal into his shell (Brey, 2016), and would be, in May of that year, inspiration for cartoonists of the time (Image 1). Throughout that legislature, the Government in general, and Suárez in particular, were accused of not knowing how to handle the crises afflicting Spanish society - economic crisis, political crisis and the crisis of the waves of terrorism.

Image 1: Adolfo Suárez and “Moncloa syndrome”

At times I have the feeling… …that Suárez doesn’t exist that he’s just a tv spot

Source: Diario 16 (29/05/1979)

The “news blackout” by TVE at certain times was a reflection of Prime Minister Suárez’s behaviour. The leader of the UCD, acclaimed in his first years as an excellent public speaker, as a “creature” of the audio-visual medium which he used to contact directly with Spanish society, was to suffer in this period a swift decline in popularity due to the overprotection of his immediate associates and his own reluctance to participate in parliamentary life (Fuentes, 2016: 185). Here we can see part of the explanation for the Government’s audio-visual media policy for dealing with terrorism. The other part is the prudence shown in order to avoid destabilizing the change to democracy.

Certain acts reported by the press reveal the UCD’s great concern for the image given to the Basque problem in the media. There are two episodes that should be mentioned, as they serve to illustrate the degree of importance attached to the question. They both took place in 1979 and are related to programmes on foreign TV channels. The first was in July that year with a report broadcast on Belgian radio-television (RTBF): The Basques and ETA”. The Spanish Government reacted to the programme with a formal complaint to the Belgian Embassy in Madrid and to their Ministry of Foreign Affairs, calling the audio-visual piece “clearly negative” due to its supposed justification of terrorism (A.G. 1979).9 The incident ended up with an official apology from the Ministry which regretted the report’s content and remarked on the constitutional duty to respect freedom of speech, along with their refusal to intervene in the selection of programmes.

A similar incident occurred with two interviews by the BBC in December 1979. The first of them was with members of ETA-pm and the second with the then Minister of the Presidency, José Pedro Pérez-Llorca. The problem on this occasion was the proximity between the interviews, as the images were not sufficiently demarcated. The Secretary of State for Information, Josep Melía, assured the press on December 7, that the matter was being “investigated” (Diario 16, 1979), clear proof that the terrorist conflict and its media treatment took a central place among the questions of concern to the party.10

Suárez’s inaction at a moment when the terrorist group’s crimes were heightening the climate of social tension was frowned on by the main newspapers and the opposition. In Suárez’s final years as Prime Minister, he chose to limit his television appearances to the minimum, as he himself acknowledged, “to minimize the acrimony in political life” (Pelaz y Martín, 2019: 257). Despite the many voices calling for him to change his mind, only on a handful of occasions did the centrist leader appear before the media to address the political situation. The plan was intended to prevent the erosion of his public image by the perceived operation to “hound” him (Contreras, 2016). That the strategy failed can be seen from polls such as those appearing in several dailies over the summer of 1980. 48% of Spaniards disagreed with his way of governing (El País, 1980a).

Thus, Suárez delegated the task of “facing up” to terrorism to members of his Cabinet, some of whom, such as the Minister of the Interior, Ibáñez Freire, were likewise criticized for their “weak” or non-existent appearances on TVE (Campmany, 1980). Perhaps one of the reproaches with most resonance came toward the end of 1979 following a chain of events11 which ended with the kidnapping by ETA of the centrist parliamentarian, Javier Rupérez, claimed by ETA. The lack of explanations concerning what had happened would lead to papers such as Diario 16 demanding that Mr Freire appear on television to update the public on the politician’s predicament. In the opinion of that newspaper, there was no alternative as the situation was unsustainable: “if being bombarded with questions by journalists on live TV makes Ibáñez Freire uncomfortable, we feel sorry for him, but it is something he has to swallow” (Diario 16, 1979a).

Suárez’s decision to not appear on the small screen only varied on the few occasions when his presence before the cameras was practically obligatory. It is worth looking at his first television address following the General Election of October 31, 1979. The election had been called largely due to the escalation in terrorist activity and the killings of the socialist activist Germán González López, the first victim since the referendum passing the Statute of Guernica, and of the Guardia Civil, Manuel Fuentes Fontán. “Suárez breaks his silence” (Pi, 1979) or “Suárez enters the arena” (ABC, 1979a) were among the headlines the next day. The Prime Minister’s reluctance to appear before journalists ended with that public act. ETA terrorism and future regional autonomy were the key points of his speech. Rejection of a new amnesty was one of his assertions. And a possible tour of Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa and Álava, one of his promises.

This appearance in Moncloa, amply covered by Televisión Española, was intended to be a bombshell for public opinion as they saw the Prime Minister coming out of his “bunker” to deal with the principal problems facing Spanish society. Terrorism, naturally, was one of them, and would continue to be so throughout that year and into the next. Several months were to pass before Suárez agreed to a similar act. Not even the killing of the centrist Juan de Dios Doval was enough to mobilise a leader who was politically all but spent. On that occasion, it was Carlos Garaicoechea, for the Telediario of October 31 (Ruiz de Azua, 1979), and Juan José Rosón, during the night of November 8 (Diario 16, 1980c), who handled the awkward task of turning up on TVE to condemn the attacks.12 Carlos Dávila’s reading of this was as follows:

Adolfo Suárez, it would seem to be clear, feels that terrorism is not to be destroyed by regular appearances on television, which, while not untrue, largely contradicts his tendency in his first days as Prime Minister to use the small screen to infuse the country with a sense of confidence, to transmit security and a sensation of authority. (Dávila, 1980)

As for this last point, we should turn to the reflections of the author who possibly has dedicated most effort to the life and work of Adolfo Suárez, Juan Francisco Fuentes (2016: 174), on how much the camera “liked” Suárez and the utilization of the small screen as the axis of his political project, recalling how his television addresses became a frequent means at moments when it was necessary to send a message of hope to the nation. The same author adds: “the consolidation of our democracy supposed greater protagonism on the part of Parliament and the political parties, and in parallel, a lessening of the weight of the charismatic powers […] more democracy, more Parliament; more Parliament, less television”. The result of this equation was especially damaging in terms of the fight against the terrorists, as it gave a sensation of incapacity on the part of the head of the Government to face ETA’s crimes. In Parliament itself, that feeling was shared by deputies such as Miguel Ángel Arreonda, who recommended the Executive employ all the mechanisms in its arsenal to prevent society’s moral collapse. These were his words:

The Government, using the means at their disposal, must make a mark on the conscious and subconscious minds of all Spaniards (…) We ask the Government for efficacy in the widest sense, and that they be capable of transmitting a sense of that efficacy throughout society. (Congress, 1980, p. 6683)

These words from the Andalucist politician came on the parliamentary floor on June 24, 1980, in which the media treatment of terrorism was once again subject of debate. In that debate, the socialist Gregorio Peces-Barba denounced the frivolity and distance with which the terrorist problem was communicated to society in State media. “We believe it is erroneous to think that this a justification of terrorism”, he said. Antonio Jiménez Blanco, representing the UCD, offered a reply which is revealing as to how that party interpreted the role journalism had to play. Months before, Jiménez Blanco had recommended “self-control” to establish a fair balance between information and avoiding publicity for terrorist acts:

Concerning the subject of information, Mr Peces-Barba knows perfectly well that the problem of informing about terrorism is a problem that arises at every level (…) It is, without a doubt, necessary to give a certain amount of information about the offence and the violence.(…) But the problem arises when deciding how and how much information to release (…) The people must be informed, and they are, as we live in a free state; but, this is a truly delicate matter. (Ibidem, p. 6690)

5. Conclusions

The controversy surrounding television treatment and coverage of ETA’s crimes is not exclusive to the years 1979 and 1980, but the social, political, and historical context of the period calls for specific analysis. The unfortunate televised comments of Rodolfo Martín Villa, Minister of the Interior at the time, following the funerals of Constantino Ortín, Military Governor of Madrid, in January 1979 –“if we don’t finish off ETA, it’ll be ETA who finishes us off”– served to suggest a double dimension to the Basque problem. The first, that the struggle against terrorism would be long and costly, which turned out to be true. And the second, corroborated by the repercussions of those words, that communication on the subject through the most powerful mass medium of the time was far from an easy task.

Throughout the so-called “years of lead”, in which ETA took the lives of Spaniards week after week, both television, in the way it presented events, and the UCD Government, by virtue of their audio-visual strategy, made clear the complex dilemma between informing the population or not doing so. The technique of “selective treatment” that had predominated in previous years, clashed with the requirements of the constitutional framework. The need to make TVE a more independent medium, under parliamentary control, as well as the obligation to normalise the practice of accountability to the citizens, were understood to be basic tenets of the new way of governing. On the other side of the scales was terrorism itself and the ongoing destabilization of the Spanish Transición.

In a period marked by political confrontation around the democratization of the public medium, any manipulative use of the small screen was seen as an attempt by the Government to continue using the channel for its own ends. As regards the terrorist question, criticism of governmental interference in the work of TVE was similar to that made throughout the legislation, regardless of the fact that on this point the intention may or may not have been to prevent general unease and the consummation of the “terrorist ritual”. Protests about the omission of certain facts formed part of the usual messages in the press and an opposition committed to a battle for control of the medium. But comments about “overabundance of news” and the normalization of violence show that the problem of terrorism in the media went beyond party politics.

Press interpretations of the content broadcast are proof of the dilemma facing TVE in the struggle against ETA. The audio-visual medium was, at the time, plunged into a situation where it was necessary to keep up the old prudence to avoid putting the shift to democracy at risk and in which the continuous succession of attacks made it impossible to speak of them as isolated events. That “news blackout” that came about on occasions contrasts with the continuous references to the attacks in news programmes and in the monographic programmes where the terrorist group and its crimes were the story. Attempts to minimize the impact of the attacks and the censorial practices belonging to other times serve to illustrate the delicate task of putting the whole question on the television screen.

As for the Government’s role, and, in particular, that of Adolfo Suárez, the same difficulty of whether to inform or not, suffered by TVE and its professionals, had the Prime Minister in check, as he decided not to rely on the formula he had employed during his first years in power. The entry into force of the Magna Carta meant an end to the use of television as an expression of pre-constitutional prime ministerial power and put an end to the trick of a TV message as a bombshell to “build Spaniards’ confidence in him or disarm a political crisis” (Fuentes, 2016: 174). In the wearisome toil of the fight against terror, Suárez was clearly one of the figures who suffered most damage, if not the most of all, possibly due to the surrender of his role as “video-leader” which had served to consolidate him. On top of this came his retreat into his shell and the “hounding” which was so implacable in the latter months of 1980.

Suárez’s decision to not appear on television, to appear on a handful of occasions –leaving “more darkness than light”, as Pedro J Ramírez was to say (Ramírez, 1980)– or to delegate the task to other members of his Cabinet, were symptoms of that “Moncloa syndrome” which led to his plummeting popularity. Though the Prime Minister’s invisibility may have been due to a real intention to not add more drama to political life, it was not taken well by public opinion, considering the polls that question his way of governing and others that point to the terrorist problem as one of the most serious in contemporary Spain. In Parliament, the debate on whether to inform, not inform or inform in an adequate manner shows the level of interest taken by the other political forces. Television opted for a balance. A partial, prudent, adequate or ineffective balance, depending on the opinion of the various actors and media.

Papers such as this, the others mentioned in this text and yet others that are surely to come, certify the relevance of a line of research still little pursued. Here we have placed our focus on public television and on years marked as never before by terrorist violence. ETA’s presence in Spanish reality was to continue for decades, and study of this area may serve as a guide to future works. The possibilities are numerous: contrasted or transnational viewpoints, and new techniques and methodological tools, among many others. All of this will serve to give a more rounded, complete, and, of course, necessary vision.

6. Acknowledgements

This article has been translated into English by Brian O´Halloran.