1. Introduction

The analysis of political mythology is one of the most prolific streams in the field of myth criticism and the studies on social representations for good reason: a myth is a way that the collective macro-narrative, the cultural matrix that gives meaning to each specific culture’s system, has historically taken shape in societies. Nowadays, the study of political myth is applied to the transdisciplinary analysis of any foundational macro narrative in any society, which is a long way from the rigid structuralism that presided over social anthropology around the 1950s or the conception of the mythological analysis limited to the study of false beliefs that governed life in primitive societies.

The prevailing trend in the first half of the twentieth century was to focus mythological analysis on the study of the so-called “mythical” or prescientific societies, which were considered as ignorant of their past from a Neocolonial and Eurocentric perspective as they often understood myths as false manipulative stories instead of a narrative device for social cohesion. However, a growing consensus began to take shape in the seventies during the so-called linguistic and postcolonial shift and the trend towards transdisciplinarity, which stated that all political communities, although enlightened and secular, had more recent and ancestral mythical roots that aimed to elaborate simplified collective responses to inevitable questions. Oyaneder (2003, p.94) sums this up in the following, “the function of the myth is to give the individual a vision about things and of themself. Such a vision is necessary for a person as it gives them the orientation s/he originally lacks. (…) myth is, in its origin, the result of primordial humanity’s efforts to formalise reality as a coherent whole with a given meaning (…) knowing this order allows the individual to locate himself adequately in it”.

Thus, a mythical analysis will ask the following questions: How was our social order formed? Who participated in its creation, and what values did they defend? What direction is this order taking us? Who forms a part of our community, and who is left in the margins? What memory do we need to convey to protect (or subvert) this political system, etc.? According to this constructivist perspective, how these questions are answered and organised in social macro narratives embodies each societies’ collective and heterogeneous identities with their ideological repertoire, coexisting narratives at each particular historical time, mythology, political diversity, tensions, and shared ties.

Since ancient times, myths have had the connotation of falsehoods and mediation. Originally, the Greek word “mythos” is opposed to “logos”- to the rational understanding of social history- and it has been often translated as “fable”. However, later in Latin, it became the lexeme “mittere”, which appears in verbs such as “to emit” or “to transmit” (Núñez, 1999, p. 50). This highlights the link between the mythical and the “mediated”, which is conveyed intergenerationally. Myths have traditionally referred to narratives prior to the current historical time, which recount the exploits of superhuman beings who made the world we live in possible (the origin of the sea, sun, fire, etc.); their adventures inform us about natural laws. This normative dimension has linked myth and politics since before written culture. In classical Greece, Babylon, or the Roman and Egyptian empires, the systematisation of these oral narratives, transcribed by poets and philosophers such as Homer or Hesiod, as well as the divinisation of political figures such as Pharaohs or emperors (Domitian went so far as to declare himself a deity, constructing his own mythical narrative for an imperial cult during his lifetime). They channeled a symbiosis between mythological narrative and political power that has persisted since the origin of agricultural societies to the present day (Campbell, 2017).

Thus, “the religious myth, in general, did not disappear (…) it became compatible with rational schemes in theology (…) various mythical narratives that came after each other judged the others as false (…) In other words, depending on the narrative that was felt to be true the others were consequently considered as false. However, the disregard of mythical roots of one’s own “truth,” was not exclusive to formally religious narratives, but was also manifested in the “rationalist” schemes of thinking, from Antiquity onwards, in a process that continues to the present day” (Oyaneder 2003, p. 97). Indeed, within the notion of a classic or contemporary myth, put forward by authors such as Campbell (2015), Vernant (2013), or Detienne (1985), this anthropological constant does not oppose the advance of science or democracy but goes hand in hand with civilisation’s development and effectively conveys its growing complexity. This is because the order of cultural life can be based upon major stable beliefs, devices that result in ideology and ritualisation that establish shared meanings, and civic normativity. In this sense, they act as organising devices of social life, democracy, and modern structures of knowledge production. It is important to note that myth plays a performative role; it provides explanations and acts as a driving force: the narrative we give ourselves in each context will guide social action, human creativity, and the thinking of the time, as Raquel Caerols states (2015, p. 38), “all our ideas about creativity, artistic creation and geniuses are the fruit of myths born in the light of a historical context. Societies aspire to understand and explain themselves through these constructions. Myths represent symbols, symbols upon which the ideology of civilisation is built, but they are simultaneously part of thought and the creative process, an intrinsic explanation of the human being”.

In line with this constructivist perspective, the mass media account of Spain’s Transition period (between 1975 and 1982 approximately, with slight variations among authors) can be considered a founding myth in other ways than that of a farce strategically produced by those in power to control possible variations to this myth. The notion of “The Transition Myth” as manipulative has been seen many times both in journalism and academia (cf. Bustos, 2016; Constenla, 2011; Gracia, 2013; Hermida, 2015; Marina, 2014; Riveiro, 2018), particularly amongst historians critical of the blind spots in this narrative (e.g., Baby, 2012; Gallego Margaleff, 2008). However, the Transition or 15M myth can also be considered as more pragmatic, non-conspirational and a social macro narrative that effectively organises the country’s political life. The reason for this is that it contains the answers to the social majority’s notion of the origin and value of the current system of parliamentary monarchy, the repertoire of political positions that make up the democratic community (and those excluded from it), which have shared rituals (the 6 December feast, the 12 October parade, the Majesty the King’s Christmas speech, etc.). Thus it serves as a memory and contains associated political-moral values. For example, in the case of 15M, the common mythical character is the collective Hero represented in the assemblies’ choral figure, squares, marches, and surges of people that shaped this movement. This theoretical framework enables us to observe how these mythical narratives are constructed and coexist in Podemos’ early discursive streams.

Therefore, our focus is not on the veracity of the myths (irreducible repeated semiotic units in different myths) or narrative constructs incorporated into Podemos’ discourse. Instead, we emphasize their value as an indicator and example of the evolving political diversity within this party movement. Podemos’ relationship with the national political mythology shows the validity of this narrative: the study of its usage will also allow us to evaluate the internal repertoire of political strategies and how they have evolved recently. This will enable us to assess the extent to which the splits1 suffered in Podemos since 2017, as stated by current party spokespersons (Cué et al., 2019) and analysts and journalists in the mainstream media (Blas, 2019; Cruz, 2017; El Mundo, 2019; Menéndez, 2017; Ropero, 2016), respond to personalistic impulses, antipathies, and power and ego conflicts, or whether they correspond to identifiable political strategies expressed in their way of framing of this mythology. This approach will also allow us to assess when this would appear in the individual narratives on social networks.

1.1. The Transition is a mythical matrix of the post-Franco political order

At the end of the 1970s, Spain underwent a transition from a National-Catholic dictatorship to parliamentary democracy after the death of General Francisco Franco in 1975. After winning the Spanish civil war (1936-1939), Franco declared himself as the country’s dictator. The war broke out due to a military coup led by the conservative, Monarchist, Nationalist, Catholic, and Philo-fascist sectors who rose against the Second Spanish Republic. The hegemonic social narrative also reflects the violent civil war, although there are different narratives regarding the extent of the subsequent military dictatorship’s repression. The Republican sectors that fought against the dictator, who attempted to overthrow him from exile and in hiding, emphasise his cruel nature. On the other hand, the Monarchist and more conservative sectors praised him for effectively organising public life with the Catholic Church’s cooperation. Political tensions surfaced after the dictator’s death, and fears about a new conflict, terrorism, or even a new attempt at a military coup (which would occur in 1981) began to mount.

From then on, the hegemonic mass media narrative of the Spanish Transition would narrate how a series of key political figures (Franco, Suárez, Fraga, Carrillo, Felipe González, the founding fathers of the constitution, Juan Carlos I de Borbón, etc.) were able to lead a complex delicate negotiation process, requiring a sense of responsibility, a capacity to understand, inclusion, and reconciliation, and a strategic vision to lead the country from a National-Catholic dictatorship to a system of government comparable to the rest of the European democracies. Thus, when confronted with the resentment and impunity that threatened to aggravate political violence, these figures managed to build a framework of relative harmony and respectful coexistence, which established the monarchy as the keystone of the nation’s unity.

This narrative is valuable not so much because it is accurate or factual. Instead, it has been undeniably effective, resulted in decades of political stability, and enabled Spain to integrate into Europe. The ideologies sharing this common mythical matrix articulate variations; they add and contest narrative elements and interpretations according to each social group’s particular traditions, interests, and visions.

1.2. The 15M is a mythical matrix of the post-two-party political order

On 15 May 2011, thousands of people camped out in squares in hundred of cities in Spain. The demonstrations were modelled on the recent Arab Spring protests, under the mantras “Democracia Real Ya,” (“Real Democracy Now”), or “lo llaman Democracia y no lo es” (“they call it democracy, but it isn’t”). From the outset, the movement gained more than 80% of the population’s approval (Havas Media, 2011), allowing people to stay camped out for months in several Spanish capital cities. Recent literature includes a growing number of papers about this social movement. However, the current narrative study of this episode as a new mythical matrix for explaining the origin of a politically new post-two-party system in Spanish democracy is not often studied. This is not the case for the Transition. The political impact of 15M is undeniable: the dominant two-party system collapsed from that date onwards, and eight million votes were lost. As a result, dozens of new parties emerged, some of which were successful, generating a scenario of political fragmentation dominated by government coalitions at all levels of government.

The media narrative of this episode, which took on various forms and was contradictory, like any social macro-narrative, incorporates recurring themes that allude to a new political time: the image of the people taking to the streets to renew democracy and call for a new social contract. These images are echoes of the French people’s uprisings, which are usually described as the origin of modern democracy, or of the well-known “We the people do ordain and establish,” the American independence’s mythical formula, representing the people in the abstract (not an ideology, social group, or specific party) who established a new order. 15M also precipitated the massive use of the ICT for social mobilisation (Hernández et al., 2013, p. 67), especially the platform Twitter (Álvarez-Peralta, 2018, pp. 109-115), and decisively renewed the repertoires of trade union protest (Gago, 2016, pp. 50 y 59). As Espinar-Ruiz and Seguí-Cosme (2016, p. 16) have highlighted, “it is difficult to overestimate the influence that the 15M has had on some actors’ communication in structured Spanish civil society (…). The communicative scenario has acquired more actors and overtly political meanings, and the field of study has consequently become more intense in political concepts and debates”.

2. Objectives and methodology

This study has the following objectives:

- Main objective: To identify what discursive approaches Podemos has given to the Transition and the 15M political myths.

- Secondary objective 1: To map out the discursive and political strategies that highlight these mythical constructions, as well as their evolution, if any.

- Secondary objective 2: To assess the extent to which the split at the second Podemos congress1 responds to personalistic impulses, personal antipathies, power and ego conflicts, or different political strategies found in different approaches to these mythologies.

- Secondary objective 3: In this case, to evaluate when these strategic differences would appear in their discourses on social media.

Twitter is considered as the digital social network for public orientation par excellence because it has potential political and journalistic uses, as opposed to the more interpersonal and semi-private networks such as Facebook and Instagram (Farhi, 2009, pp. 27-30; Neuberger et al., 2019, p. 1260). The corpus analysed in this work comprises seven official accounts from Podemos and tens of thousands of messages posted on this network from the party’s foundation on 17 January 2014 until its entry into government on 13 January 20202. The final sample for the in-depth qualitative analysis is comprised of 409 messages. They are analysed based on whether they included specific lexemes related to keywords that identify the presence of the two mythical constructions.

We apply the “coding and counting” approach for a computer-mediated discourse analysis (Herring, 2004, pp. 343-345; Torrego & Gutiérrez-Martín, 2016, p. 13), the critical concepts have been operationalised in empirically measurable terms. For this purpose, we have gathered 28 codifiers in two macro-categories corresponding to the two mythical narratives, which identify narrative types that are specific to both narratives. From a sample of tens of thousands of tweets, the final sample is composed of all the messages that directly refer to any of these key terms in their lexematic variations (i.e., including typical endings and co-occurrences):

- Key terms from the Transition: Transición, democracia, 23F, golpe, Franco, Suárez, Fraga, Carrillo, Tejero, Felipe González, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, Régimen del 78, R78, 1982, movida.

- Key terms from 15M: 15M, 15-M, 2011, mayo, acampadas, asambleas, plazas, quincemayis*, Sol y mareas.

Although it proves to be effective, these semantic sets can be neither exhaustive nor infallible. To disambiguate and rule out polysemic occurrences of false positives, a direct contextualised corpus review is employed. This methodology does not analyse a random selection; instead, it analyses the complete set of messages that refer to the topics.

An advanced search system of the Twitter platform was used to retrieve the tweets. It was applied to seven official spokesperson’s profiles corresponding to the party’s official profile and its initial leadership and founding team (Blas, 2019): Pablo Iglesias, Íñigo Errejón, Juan Carlos Monedero, Carolina Bescansa, and Luis Alegre. Different sensibilities have been incorporated for a broader overview, including Alberto Garzón’s profile, leader of Izquierda Unida since 2013, and the coalition of Unidos Podemos since May 2016. Thus, we have a total of 28 lexematised key terms and seven official accounts from over six years, resulting in a comprehensive selection of 409 messages in the final sample for the qualitative and quantitative analysis. The aim is to map its distribution over time, as well as between accounts, narratives, and myths, as a basis for the subsequent discursive and semi-narrative analysis, oriented towards categorising and interpreting these myths acting as political mythology. This will allow us to map out the underlying discursive and political strategies and their evolution over time.

The guiding questions for this inquiry are therefore the following:

- IG1: Have the foundational mythical narratives of the political context, such as the 15M and the Transition, been treated differently within the Podemos Party?

- IG2: Have these constructions evolved in the period between the party’s foundation in 2014 and its entry into government in 2020?

- IG3: Do these different approaches correspond to different political strategies and/or theoretical frames of reference in the splinter fractions after the second Podemos congress?

The central underlying hypothesis is that the split does not respond to egos or personal differences, which has often been claimed, instead it is the result of divergent political strategies in clearly differentiated public narratives existing in the early stages of the party.

The reason why the discourse is analysed through the digital social network Twitter, as opposed to other media, is because it can be easily accessed compared to television and radio archives, but also because we can find a broader range of more relevant profiles such as Alberto Garzón’s, Íñigo Errejón’s or Juan Carlos Monedero’s, who are extremely important to this research’s objectives. They exert significant influence over the party’s running at different periods; they do not receive the same media visibility as Iglesias, who was almost the only spokesperson during the first few months of the party. However, they were active on Twitter. Moreover, this social network allows us to contrast discourses from the corporate account with more personal discourses from the politicians’ respective personal accounts. These personal accounts are more often informal and show the fragmentary perspectives we are looking for. For the sake of simplifying the methodology, only the textual part of the verbal-visual communications is taken into account; the visual analysis of images or videos are not considered at this stage of the analysis. However, their content can be briefly summarised when textual analysis requires it.

This methodology is rounded off with direct interviews with five of the party’s leaders, four founders, and a network team coordinator. Reponses we will quote throughout text3 were gathered to strengthen or rule out some of the potential interpretative hypotheses. The content analysis based on “coding and counting” techniques combined with multimodal discourse analysis is very usual in this type of research on social representations in digital networks (e.g., Torrego and Gutiérrez-Martín, 2016; Zhang and Cassany, 2019) and on mass media mythology (e.g., García-García et al., 2011).

3. Results

3.1. 15M mythical meanings in Podemos’ discourse

We will begin by analysing the presence and framing of the most recent mythical narrative related to 15M in reverse chronological order, which is often applied to explain the origin of the Podemos party movement and give meaning to it both in academic analyses (Calle Collado, 2016 pp. 85-87; Iglesias 2015, pp. 10-14; Errejón 2014, p.25; Rendueles and Sola, 2015, p.33) and numerous press headlines and opinion columns. Next, we will address the earlier and more socially established foundational myth of the Transition to democracy.

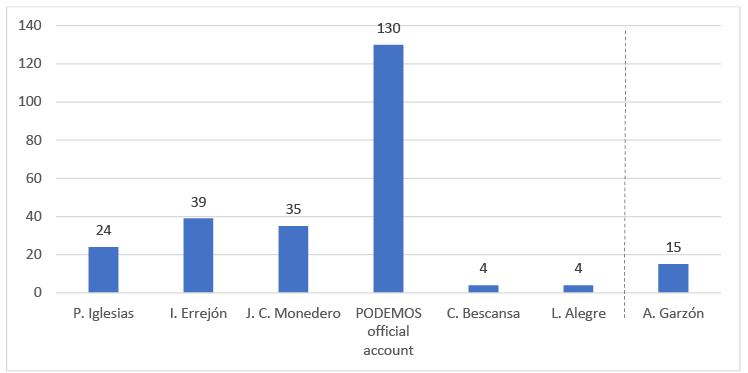

Figure 1 shows the distribution of all the tweets indirect allusion to the 15M phenomenon according to the methodology indicated. The party’s official commitment to addressing the issue can be seen, both in the corporate account and through the leaders with the most significant media projection, thanks to their status as permanent spokespeople: Iglesias (Secretary-General), Errejón (Political Secretary), and Monedero (Secretary of Constituent Processes and Programmes until May 2015, then media spokesperson). The sample distribution is quite balanced among the three spokespeople (standard deviation o=0.316). Still, more than half of the allusions appear in the official profile, showing a party decision. Although we focus on these four most prolific sources for qualitative discursive analysis, we will subsequently investigate the reason for the silences on accounts that are less active in this respect.

Figure 1. Distribution of the tweets alluding to the 15M Movement

N= 251 tweets alluding to 15M, including Alberto Garzón’s, official spokesperson for Unidos Podemos as of 13 May 2016.

Source: created by the authors

Based on the initial semi-narrative exploration, the allusions to 15M can be grouped into two primary narrative constructs or periods. In the first construct, the 15M phenomenon is portrayed as the genesis or opening to the cycle of change, as a popular outburst that ruptures the two-party system and that “opened a breach” and “represented a new country,” as Pablo Iglesias stated, giving rise to a new political time (see Table 1). This narrative operates as a founding political myth. This construction mainly acknowledges and is grateful for the 15M as the matrix of new politics in general and Podemos in particular.

The 15M is presented as an unfinished project in the second narrative construct, which is not incompatible but differentiated from the previous one. It was no longer a successful creative genesis, but rather an incomplete mission or an attempt pending consummation, which needs to be “carried through to the end” or “made a reality” as stated by Iglesias (cf. Tabla1).

Table 1. Examples of allusions to the two potential formulations of the 15M myth (01/2014 to 01/2020)

|

Twitter accounts |

15M as a successful genesis in a new time |

15M as an incomplete mission or unfinished project |

|

@Podemos’ tweets |

|

|

|

@PabloIglesias’ tweets |

|

|

|

@IErrejóns’ tweets |

|

|

|

@MonederoJC’s tweets |

|

|

For the complete selection of tweets, see DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.13506642

Source: created by the authors

On a grammatical level, the first narrative alludes to a perfect, finished tense, while the second uses an imperfect tense, a durational modality, pending conclusion. Therefore, this second narrative is less mythical in the sense that it is less foundational and earlier. Otherwise, it fulfills the function of registering the Podemos party movement as a protagonist of this ongoing mythological narrative. Thus, the mythical Hero’s journey constructed by Podemos is confirmed (Aladro Vico, 2018, pp. 103-105), enunciator and Hero coincide, or at least overlap in their choral dimension.

Podemos’ spokespeople’s discourse oscillates between two opposing strategies of relating to 15M. While the first mythical construct affirms the inability to represent this movement, highlighting the difference with today, in the second narrative, there are explicit attempts to appropriate the representation of the 15M’s legacy, whose mission is openly judged as unfinished. Podemos is thus presented as the interpreter, heir, and continuation of that social outburst, as a Promethean subject called to fulfill the nation’s destiny and carry out the mission of giving birth to a new country. Both representations are narratively compatible, although they point to very different social meanings of the 15M.

Despite the various differential nuances between spokespeople, including Luis Alegre’s, Carolina Bescansa’s, and Alberto Garzón’s, a common mythical matrix cuts across the entire Podemos’ leadership (2014-2016) and Unidos Podemos’ (2016-2020)4. In the case of Garzón, leader of IU (Izquerda Unida) and PCE (Spanish Communist Party), both aspects described above3 are also expressed. There is also a third strategy, not present in the other spokespersons’, which is to rebuild the 15M as a specifically left-wing movement, with left-wing values. It is expressed in messages regarding the coalition with Podemos such as, “There is a thread that connects the Republican tradition with Socialism and 15M”, or “Today is a moment for occupying the squares again, to call for participation in our future. For a constituent process. #VivalaIIIRepublica» (#LonglivethethirdRepublic). This type of connection between themes is not present in the two constructions mentioned above.

3.2. The Transition’s mythical meanings in Podemos’ discourse

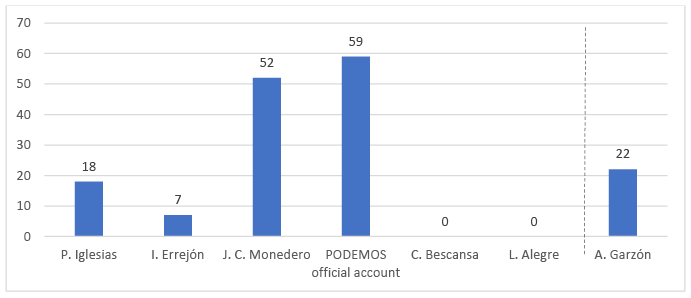

On the other hand, if we observe the construction of the political transition myth in Podemos’ digital discourse, the situation is different. Despite the narrative being older and therefore very well established both in the newspaper archives and throughout broad sectors of the Spanish population, the political strategy is less coordinated within Podemos: we can find more confrontational and openly incompatible versions. First of all, the number of allusions to this narrative is surprising in the quantitative analysis, only 37% less frequent than 15M (cf. Figure 2), even though it deals with an episode 35 years before the foundation of the party, and in principle, it is not as directly related to it as the 15M movement.

Figure 2. Distribution of tweets alluding to the Spanish political Transition between 17/01/2014 y 13/01/2020

N= 158 verbal-visual messages, including A.Garzon’s, whose official role as a spokesperson in Unidos Podemos began on 13 May 2016

Source: created by the authors

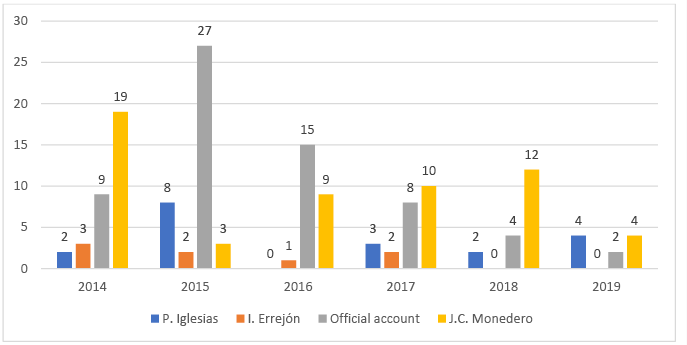

There is a significant difference in the frequency that the different spokespersons post. Some of the leaders do not even post about the Spanish political Transition; such is the case of Carolina Bescansa, Luis Alegre, and Iñigo Errejón, who posts few tweets about it. The distribution over time (Graph 3) shows how this discourse was concentrated in 2015, except in Juan Carlos Monedero’s case, the 40th anniversary of the dictator’s death, and the formal celebration of the anniversary of the Transition to democracy. This is true for the prominent spokespeople’s accounts, the official party spokesperson, and Pablo Iglesias’.

Figure 3. The volume of tweets per year alluding to the Spanish political Transition between 17/01/2014 and 13/01/2020

For the complete set of tweets, see DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.13506642

Source: created by the authors

The unequal distribution of this discourse among the seven analysed accounts draws attention to the most polarised cases: Monedero and the official party account post more than 50 messages. At the same time, Errejón only writes seven, and Bescansa or Alegre do not address the issue on Twitter. Approximately half of the statements correspond to messages from Juan Carlos Monedero and Alberto Garzón (only four of Garzón’s tweets are before the IU-Podemos coalition), who represent a more traditional left-wing sensibility. When asked about the reason for this difference and his silence regarding the matter, Luis Alegre (27/12/2020) replies:

“We did need to talk about 15M, but… the Transition was a subject that, insofar as we could hide it, it was preferable, because we could only speak in contradictory terms, what could we do, if we did not think the same about it. (…) it has a very strong generational bias, and it made us choose one generational segment in order to address and ignore another”.

Due to this response, we can rule out sampling errors or simple chance. There was a conscious political decision to avoid the topic and not provoke generational biases and express internal controversy about it. Carolina Bescansa3 was interviewed (29 December 2020) about the same subject; she confirms this assessment:

“From the beginning, there was an internal debate about how we approached the reading of the past; a part of us understood that anything that referred to the frame that went beyond the 15M was counterproductive, it did not serve to build unity, but rather served to divide (…) We decided not to get into the trouble of vindicating the extreme left-wing discourse of the critical vision of the Transition. Others, on the other hand, came from the communist tradition and were in the business of recovering memory in a sense that was… well, very un-Marxist (…) One of the keys to the success of this [Podemos] was precisely not to devote any time to preparing a critical review of the past (…) and to devote all their energies to building consensus in the present”.

In the same vein, the first Coordinator of the Podemos Networking Team, Eduardo F. Rubiño, was interviewed (26 December 2020) and replied:

“Monedero has always been much more in tune with the traditional left-wing that wants tell the story of the Transition as being a trap, (...) the truth of what happened, not to make concessions, (…) But this question of transversality, of not getting involved in the battles the past left wing’s, all the traps that had prevented us from reaching the general public, largely involved assuming that the battles had been somewhat lost beforehand and that therefore we were not going to undo Victoria Prego’s report5 now and tell everyone that what they had never been told took place”.

Monedero was interviewed about the matter (30 December 2020) and confirmed the strategic disparity:

“For Errejón, Bescansa, and Alegre, what were not “winning frames” had to be left out of the debate because they could not be won there. We discussed whether what was not talked about disappeared from the agenda or not. My opinion was that it should (…) And Errejón’s hypothesis, initially shared by Iglesias, was not about changing what people thought but operating within what was hegemonic. And from there, try to change it.”

Beyond the quantity and the distribution of mentions of this narrative, after counting and coding them, semiological analysis of this discourse reveals a broader series of categories than in the case of 15M. Still, above all, they are distributed differently among the spokespeople studied.

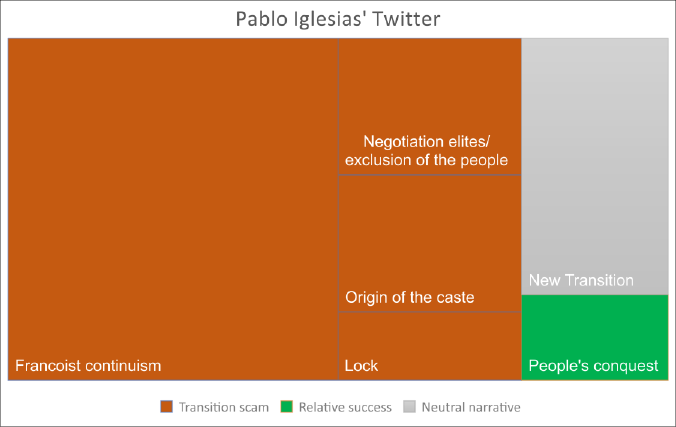

In the case of Pablo Iglesias, there is a predominant reconstruction of the Transition as a process led by corrupt elites (the famous “caste”) clinging to their positions of power, immobile and manipulative of the historical narrative, and even violent3. This vision is expressed in tweets such as:

- My father on the politics of the Transition and its caste today, Brutal! [Cadena SER audio] (12 March 2014)

- “In this country, a generation carried out the transition, and thirty years later it is still at the head.” (30 March 2014)

- CiU negotiated the lock on the constitution with Fraga. (12 May 2015)

- Today, after more than 40 years of democracy, Franco’s mummy has left el Valle de los caídos. It is good news for Franco’s remains not to be in Cuelgamuros but in the oligarchies that enriched themselves with the dictatorship and in part of the state apparatus. (24 October 2019)

In only two of his messages, Iglesias proposes a different, vindicable construct of the Transition, comparable to the process that the 15M would be opening up decades later and Podemos would be completing:

- In @Fort_Apache_, we debate the Transition and its potential analogies with the change of era we are experiencing. (14 June 2015)

- “A new transition” My article today in @el_pais. (19 July 2015)

However, in the party’s official account, both stances in the party leadership are reflected, and both narratives are better balanced. The Transition is a false narrative that needs to be challenged and an achievement to be continued or repeated3. For example:

- In the Transition, what could be done was done. But the story was an insult to those who paid a prison sentence as the price (18 November 2014)

- The #OperaciónPalace game is right about one thing: The Spanish Transition was a farce. From that dust our mud. (23 de Febrero 2014)

- The consensus of the Transition has been undone. We don’t want a second version but a first democratic rupture. (3 June 2014)

However, it is based on the design of the political Campaign for its first local, regional and general elections (March to December 2015), during its first well-thought-out and professionally designed electoral Campaign, where it will be decidedly committed to the second type of construction, the Transition as a valuable legacy to continue3:

- We are living through a new transition, and we have to face it at the level of the state (16 December 2015)

- Some did not understand that this country was changing and that we are living through a new transition (17 December 2015)

- 15M opened the way for a new transition in Spain (5 December 2015)

- We are ready for a new Government and to lead a new transition in our country (18 December 2015)

- In these elections, we can see a change of era. We are living through a new transition (12 December 2015)

- I think we are entering into a new era; a second transition is coming in which it is going to be necessary to rise to the occasion #PabloEnLosDesayunos (16 December 2015)

- We are living in a historical time; we are living through a second transition #EsElMomentALC (11 December 2015)

- 15M opened the way to a new transition in Spain #LeyDeImpunidad (5 December 2015)

- 15M started a new transition in Spain (6 December 2015)

This more unified, internally coherent narrative is created when Íñigo Errejón is head of the Campaign as the Political Secretary of Podemos, which is consistent with Monedero’s statements in his interview: he is the exponent of this mythical construction in Podemos’ leadership. In Íñigo Errejón’s Twitter account, meanwhile, not only is there less about this issue, but the second approach predominates, characterising the Transition as a success, in line with the official party line during the campaign3. For example:

- Today’s problems cannot be fixed by remembering the achievements of 40 years ago. The Transition was a successful deal, but it is time to talk about 2017 (29 June 2017)

- Faced with Tejero, the people declared democracy and popular sovereignty. Today we say the same in the face of those who seek to steal the institutions. (23 February 2017)

In Monedero’s case, on the other hand, the opposite construction predominates, constructing the signifier Transition as a scam or fraud to be challenged, and contrasting the idea of “First Rupture” in numerous examples with that of the “Second Transition” (which is the one used by the party in its electoral Campaign). This corroborates what we have been mapping out, seens in graphs 4,5, and 6.

For example:

- To Salobreña this Monday! To discuss the Transition and the crisis of the regime. Instead of the 2nd Transition, the 1st rupture. (12 January 2014)

- 22M marks the beginning of the first rupture. Suarez’s death is going to be used for a second transition. (22 March 2014)

- Impeached daughters of the king, wavering kings, bearded princes…This sounds like a second transition. (7 January 2014)

- Suárez dies after the largest democracy march and years with Alzheimer’s. Neither a second transition nor more lies: for the first rupture. (23 March 2014)

- Suárez dies, and with him, the Transition of ‘78. May the earth be light for them. (23 March 2014)

- I’m sick to death of people saying that Suárez was the first President of democracy. And other things. (24 March 2014)

- There is an invisible line between the Transition and the Plot. Let’s discuss it today in Albacete. Before they hollow out our democracy. (12 May 2017)

- Now it is really time for that second Transition that so many have talked about. And without saber-rattling, it will have something of a first rupture. (2 October 2017)

Podemos’ official account shows a very different approach to the myth of the Transition if we look at its publications before the Vistalegre 2 congress was held and after it, when the team responsible for the social media, aligned with Errejón, was replaced by another, aligned with Iglesias (cf. note 1). Before that date, Errejón’s team gave little priority to the notion of the Transition as a hoax on their official account. Instead, it was given much more space in the account’s activity after the current led by Errejón was dismissed (figures 7 and 8). G. Paños, member of the Errejonista current and head of state networks team until his departure after the second congress, confirms in the interview (28 December 2020) that he had total power to decide what was published on the party’s social networks, despite the internal conflicts between currents:

“There are different people that take care of the account at different times of the day, but all the people belong to the same team and have the same management. I managed Podemos’ social media team until I stopped managing it, and I never had any interference. I never even… I mean, I never had any interference of “you have to put this whether you like it or not” or “you have to publish this, you have to do that,” until the problems started, obviously, within the leadership.”

On the other hand, when asked about how the handover of power over that team was done after the second congress in 20176, he replied that the handover of power was done immediately, with no transition period:

“I draw up a document on the handover, so that they sign it and can… in case they have any problems later so that they are not going to say anything to me, and until the last day that I manage it, I manage it and from the day that I stopped doing so, and they were responsible for it… there is no transition period between one and the other”.

These two facts (full powers until the second congress and immediate handover after it) are consistent with the notable difference between different accounts regarding the importance given to the Transition and the party’s official account before and after that date.

Figure 4. The proportion of tweets about each narrative aspect of the Transition in P. Iglesias

Source: created by the authors

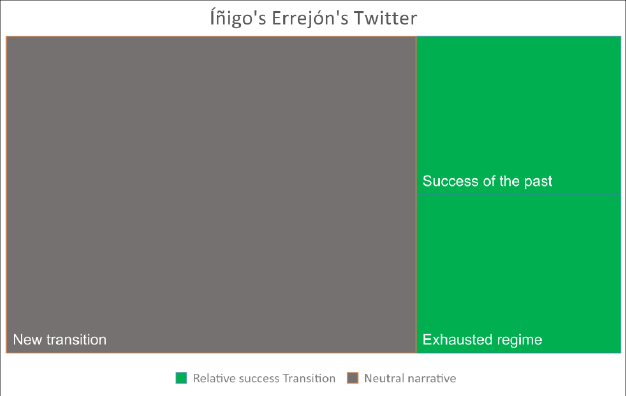

Figure 5. The proportion of tweets about each narrative aspect of the Transition in I. Errejón’s tweets

Source: created by the authors

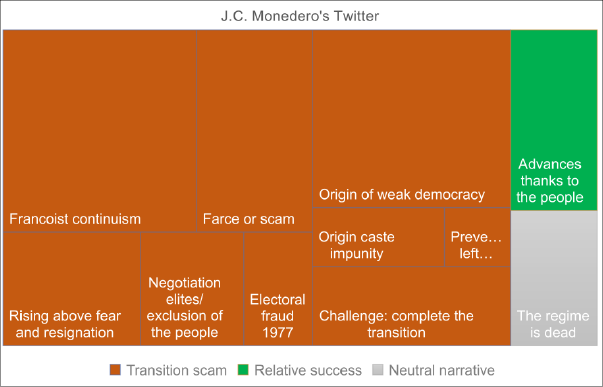

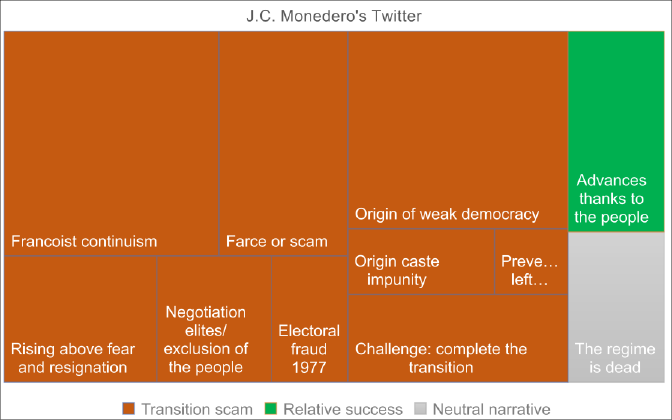

Figure 6. The proportion of tweets about each narrative aspect of the Transition in J. C. Monedero

Source: created by the authors

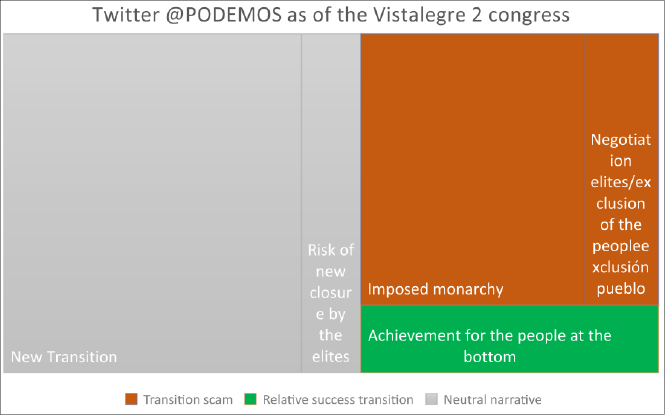

Figure 7. The proportion of tweets about each narrative aspect of the Transition on Podemos’ official account until the Vistalegre2 congress

Source: created by the authors

Figure 8. The proportion of Tweets about each narrative aspect of the Transition on the official Podemos account after the Vistalegre2 congress

Source: created by the authors

As for Alberto Garzón’s3 digital discourse, the construction of the myth of the Transition is similar to Monedero’s, which corresponds to the traditional discourse in parties such as Izquierda Unida and PCE. Therefore, it is coherent with Garzon’s stance as leader of these parties.

4. Discussion and conclusions

In different narrative constructions that have coexisted among Podemos’ leadership, we have seen how different mythical narratives explain the current political context. While when it comes to the 15M, it is the genesis of the change of cycle and the alternative that adds narrative themes such as the unfinished mission that Podemos must complete. This does not correspond to the splits that have subsequently occurred. However, this is not the case of the Transition as the genesis of the post-Franco democratic system.

As a result of this exploration of the mythical matrices in Podemos’ digital discourse, we can draw the following conclusions:

We note the unitary and cohesive commitment to a strategic discourse towards 15M, which elaborates a mythical narrative of the movement as a foundational act of the new political context, found in a double narrative: the 15M as the genesis of a new time, as a gap in the country’s political chronology, and at the same time as an unfinished mission, as an ongoing project.

This double discourse cross-cuts the prominent spokespeoples’ discourse sustained over time

In the case of the mythical narrative of the Transition as a founding process of post-Franco democracy, in contrast, we have found three significant declinations that we can identify within three metaphorical frameworks that are not entirely mutually exclusive among Podemos’ founding leadership: 1) The Transition as an achievement or success to be vindicated and repeated (summed up in the slogan “Thanks 1976, Hello 2016!” or calling for a “second Transition”); 2) The Transition as a failure or botched job, forced by the pressure of the general public’s struggles but unsuccessful; and 3) the Transition as a manipulative false narrative to refute and “demystify,” which hides a pact between elites leaving Franco’s power structures intact (hence the idea of “first rupture”). Note that 2) and 3) are compatible and nuanced variants of the same mythical matrix.

The choice of Errejón, Bescansa, and Alegre, founding leaders outside the party, would be to avoid the issue or adopt the first framework for electoral or strategic reasons, as we confirmed both in the analysis of the social media and from the interviews.

In contrast, Monedero’s political stance is practically the opposite. It converges with the IU leader Alberto Garzón’s, insisting on the second and third framework for justice and historical memory.

Iglesias’ and the party’s discourses have more hybrids between the three frames mentioned above.

These stark differences regarding the construction of the Transition’s mythical past are present from the beginning. They correspond to the conflicts that would later emerge as splits and ruptures among the founding leaders of Podemos, which contradicts the dominant interpretation in the mainstream media that is disseminated by some current Podemos leaders (Cué et al., 2019; Blas, 2019; Cruz, 2017; El Mundo, 2019; Menéndez, 2017; Ropero, 2016), of a rupture due to a mere question of ego or personalistic ambition for power, without a correlation of confronting strategies and political paradigms that are difficult to reconcile.

5. Support and acknowledgments

This work is part of the R&D&i project “Problemas Públicos y Controversias: Diversidad y Participación en la Esfera Mediática.” (REF CS009/82/2017-R) funded by the competitive call from the State R&D&i Programme “Retos de la Sociedad” from the Ministry of Economy.

The article has been translated into English by Sophie Phillips.