1. Introduction

In the lead-up to elections, communication is intense and symbolic. In 2020, the emergence of Covid-19 altered the frameworks of the agents involved in political communication, which affected the regional elections (The Basque Country and Galicia) scheduled for the Spring of that year. The pandemic changed citizens’ news consumption, and polarised it (Masip et al., 2020). However, early studies show that conventional media was a reliable source of information (Aleixandre-Benavent et al., 2020; Casero-Ripollés, 2020) and reinforced its social role at a time of social distancing.

The literature highlights that political communication is markedly hybrid, as it combines traditional media logic with digital technologies (Vaccari et al., 2015). This dual process affects political parties and social movements (Labio and Pineda, 2016). Still, it does enable social networks such as Twitter to be critical spaces for electoral campaigns (López Meri, 2016).

The Galician elections were postponed to July 12, 2020, within a hybrid and highly digitalised framework. This research aims to analyse the candidates’ and media’s thematic priorities (political agenda and media agenda), which arose in a different communication context brought about by the pandemic. The goal is to understand the framework’s main features in the electoral campaign.

The Popular Party (Partido Popular in Spanish) has been the hegemonic power for many years in Galicia. It has always had the absolute majority since 1981 except on two occasions. This means that perhaps only singular events will have an impact on its political system. The Galician elections have been marked by a lack of nationalism, which contrasts with a transversal regionalist vision (Gómez-Reino, 2009). The study of agendas, which are the issues that occupy public opinion, the media, or the public (Humanes and Moreno, 2012; Ardévol-Abreu et al., 2020) has hardly been addressed in regional elections (Fenoll et al., 2016; Gamir Ríos, 2016).

This research aims to analyse the themes in the Galician electoral campaign. For this purpose, the political agenda is analysed through TV electoral debates and the messages disseminated on Twitter. In contrast, the media agenda is evaluated through the campaign content in the region’s leading print media. Traditional media formats and social media are usually interrelated (Rúas-Araújo et al., 2020). The goal is to evaluate the extent of assimilation between media and candidates during the electoral period.

2. Study of political communication and agendas

2..1 Twitter and political campaign communication

Politicians and journalists mutually influence each other in order to condition public opinion (Brants et al., 2009). Politicians, journalists and citizens make up the three fundamental elements of communication (Mazzoleni, 2010). Electoral campaigns are particularly intense for political communication as candidates build a specific agenda to win votes.

Current campaigns mainly take place on the internet (Stromer-Galley, 2014). In the 20th century, television was a mass media product, and in the 21st century, digital technologies have proliferated, together they have mediatised politics. Therefore, the media significantly influences the understanding of public affairs (Strömbäck, 2008) and, nowadays, social media does too (Pérez-Curiel et al., 2021).

Technological development has also led to the personalisation of politics (McAllister, 2007; Rodríguez-Virgili et al., 2011), fostering a preponderance of individual leaderships and the spectacularisation of television information (Berrocal, 2011). This trend towards infotainment affects electoral debates, as candidates prefer gimmicky messages over pragmatic ones (Wagner, 2016).

Social media, particularly Twitter because of the platform’s news immediacy, have brought about a revolution in political communication (Parmelee and Bichard, 2012; Jungherr, 2016). Twitter is used both by candidates, journalists, and voters during electoral periods (Campos-Domínguez, 2017). As digital tools become increasingly important, political parties are becoming more professional as they develop more targeted communication strategies (Tenscher et al., 2016). These tools are also significantly self-referential since parties’ and candidates’ activities serve as topics of interest on Twitter (Zugasti Azagra and García Ortega, 2018).

In a context of limited social contact caused by the pandemic, digital platforms may become even more important for political communication. So far, research on regional elections has found that candidates use Twitter unidirectionally, similar to the way traditional media does (Cebrián et al., 2013; Deltell et al., 2013). However, notable divergences depend on factors such as the party’s trajectory or their position in the government-opposition axis (López-Meri et al., 2017). Academia also tends to focus on the post-electoral periods (Casero-Ripollés et al., 2021), when the formation of a new government is being debated. The serious health and economic consequences of Covid-19 make the pandemic an ideal testing ground for using this platform.

2.2. Political and media agendas in Spain

Agenda-setting theory (McCombs and Shaw, 1972) is an influential hypothesis in studying political campaign contents, which has a long history of being applied scientifically in Spain (Ardévol-Abreu et al., 2020).

According to the initial contribution of this theory, the media can make specific themes important by selecting news items. However, newsworthy themes are not only defined in the journalistic sphere but also by two other actors in the democratic system: the political class (political agenda) and citizens (personal agenda) (Carballo et al., 2018).

The transfer of relevance always occurs within a timeframe (McCombs, 2006). Although there is a wide range of agendas, agenda-setting research has focused on analysing the media’s thematic priorities through content analysis (Guo and McCombs, 2015). Consequently, the political agenda has been studied less than the media or citizens’ interests (Castromil et al., 2020). The political agenda is more difficult to objectify, as parties’ main issues appear in a wide variety of spaces, such as their public interventions, electoral programmes, or, more recently, their social media activity (Kim et al., 2017).

Every candidates’ objective is to ensure that the campaigns’ central themes revolve around their political agenda, thus orienting the public opinion towards the parties’ stances. Beyond the fact that several variables influence this agenda, political messages on Twitter (Campos-Domínguez, 2017) and their performance in electoral debates (García Marín, 2015) are ways in which their composition can be understood. Nowadays, these channels are connected as audiovisual corporations employ strategies to maximise the Twitter following of television debates (Rúas-Araújo et al., 2020). In the case of Spain, there is a direct link between watching television to obtain information and party voting (Chavero-Ramírez et al., 2013).

The Spanish political media polarisation means that citizens obtain information about campaign issues depending on their life experience, which explains selective exposure behaviour for consuming political information (Humanes, 2014). Political parties have shown their capacity to influence the traditional and digital media agendas during electoral processes in Spain (Valera Ordaz, 2015). However, conventional mediatisation seems to give rise to interdependence among the actors involved in this agenda building (López García et al., 2017).

Campaign themes are linked to current events (Chavero-Ramírez et al., 2013). In this sense, Covid-19 was in the media spotlight in 2020 (Aleixandre-Benavent et al., 2020), although the regional elections taking place that year have a political trajectory of their own. As mentioned above, centrality in the discourse is usual in Galician elections (Ares and Rama, 2019), and it has fostered a potential prioritisation of issues in this regard. To date, studies on agendas in the Spanish autonomous regions have been scarce, but this does not mean we cannot consider research that points to the growing mediatisation on Twitter in these geographical areas (Gamir Ríos, 2016; López Meri, 2016).

3. Methodology

This research examines the thematic distribution of the political and media agendas for the Galician Parliamentary elections, held on July 12, 2020. A content analysis was carried out (Krippendorff, 2012), aimed at three discursive manifestations: candidates’ messages on Twitter, TV electoral debate, and journalistic items in the main newspapers. The study of the tweets and the themes referred to in the debate are operationalised to determine the participating leaders’ political agenda in the elections. At the same time, the news content reveals the press’ media agenda. This article has an exploratory purpose, from which several objectives arise:

- To find out the candidates’ topics for the 2020 Galician elections on Twitter.

- To evaluate attention given to leaders’ actions on Twitter, which is shown through retweets.

- To evaluate quantitively the themes addressed by each candidate in the television debate.

- To analyse the media’s treatment of the elections in the press and which issues the parties have preferred.

Regarding Twitter, specific content analysis is employed for this social network (Fernández Crespo, 2014). The type of sampling is intentional, and the study focuses on the three candidates who obtained parliamentary representation in the 2020 Galician elections Alberto Núñez Feijóo (@FeijooGalicia) from PPdG, Ana Pontón (@anaponton) from BNG (Bloque Nacionalista Galego or Nationalist Galician Bloc in English), and Gonzalo Caballero (@G_Caballero_M) from the PSdG (Partido Socialista de Galicia or the Galician Socialist Party in English). Only these accounts were chosen because these parties are traditional in the region (Gómez-Reino, 2009).

The Twitter corpus consists of all the candidates’ tweets during the election campaign (26 June-10 July 2020). They consisted of the tweets during the three days following the elections (13, 14, and 15 July) to determine the impact of the results on the messages. The Twitter data was collected using the application Twitonomy.

In the 2020 Galician elections, there was only one televised electoral debate in which the chosen leaders participated: it was broadcast by Televisión de Galicia on June 29 of that year. To access their thematic agenda, it was essential to view the debate in full and determine the time (in seconds) that each candidate dedicated to the items. The number of seconds for each leader is limited, as up to seven parties participated in the debate.

Regarding the media analysis, the corpus is composed of all the political news content about the Galician elections, published in print. The time frame is similar to Twitter’s (26 June-10 July, 13, 14, and 15 July 2020). The two newspapers analysed are La Voz de Galicia, the Faro de Vigo, El Progreso de Lugo, and El Correo Gallego, reference newspapers in different autonomous areas in the region have a newspaper archive available for researchers. Instead of combing through the newspapers, the journalistic items are gathered based on a search for keywords such as “elections” or “campaign” within the newspaper. This ensures the objectivity of the sample and facilitates later retrieval.

The data from the three objects of study (Twitter, the electoral debate, and media) were gathered using a homogenous analysis sheet on thematic issues, designed specifically for this article following mixed research principles-both digital and traditional elements (Sádaba Rodríguez, 2012). The study model is developed by only one researcher since there is not much difference in the interpretation of the themes as with other variables. In any case, the author carried out two previous rounds of training to better define the excluding categories of the file.

Despite each medium (Twitter, television, and press) having its own particularities, this research assumes that the agendas are interchangeable in these spaces. The data collection yields 386 tweets, 296 journalistic items, and 150 minutes of electoral debate as units of analysis. The categorisation sheet shows thematic aspects as a result of previously analysing themes on Twitter, following Patterson’s (1980) postulates to establish the topics that were expected during the campaign.

4. Results

4.1. Political agendas and attention generated on Twitter

Firstly, the political agendas are broken down by analysing Alberto Núñez Feijóo’s 148 tweets, Gonzalo Caballero’s 163 tweets, and Ana Pontón’s 75. The thematic distribution reveals empirical evidence of interest, including a fragmented agenda (Table 1). As opposed to this dynamic, Caballero (PSdG) and Pontón (BNG) present fewer topics. This means a greater thematic concentration of opposition candidates. The nationalist leader prioritises political events (28%), such as campaign events, and the idea of a change of cycle (26,7%). The socialist candidate also prioritises events as a primary issue (35%). In contrast, the second theme is voting mobilisation, whereby the voters’ support is encouraged.

Table 1. Distribution of the candidates’ tweets according to their themes (%)

|

Alberto Núñez Feijóo |

Gonzalo Caballero |

Ana Pontón |

Total |

|

|

Political change |

0 |

14,1 |

26,7 |

11,1 |

|

Voting mobilisation |

15,5 |

15,3 |

1,3 |

12,7 |

|

Post-election strategy |

9,5 |

4,9 |

0 |

5,7 |

|

Political events |

10,8 |

35 |

28 |

24,4 |

|

Economy/industry |

21,6 |

6,7 |

1,3 |

11,4 |

|

Public services |

16,9 |

5,5 |

0 |

8,8 |

|

Covid-19 |

8,8 |

9,2 |

9,3 |

9,1 |

|

Galicia |

10,8 |

2,5 |

10,7 |

7,3 |

|

Others |

6,1 |

6,7 |

22,6 |

9,6 |

Source: created by the author (results of greater interest in bold)

Compared to the opposition, Núñez Feijóo’s agenda deals with issues such as the economy (image 1) or public services, which shows the image of a manager that a president aims to convey. It also makes extensive reference to voting mobilisation, which may be motivated by the context of a pandemic that is conducive to abstention. In the Twitter research, the prominent leaders’ digital campaigns have revolved around political events and mobilisation.

Image 1. Examples of tweets related to the economy (Feijóo) and political change (Pontón)

Source: Twitter

It is also essential for this study to determine the quantitative impact on users who follow candidates’ messages on Twitter. As shown in table 2, the results show that the thematic elements that generate more significant interaction (retweets) do not coincide with political leaders’ most disseminated messages. This finding aligns with the literature on interaction with Twitter strategies (Larsson and Ihlen, 2015; Rivas-de-Roca et al., 2021).

The theme “Covid-19” accounted for 33.3% of the messages with more than 300 retweets and 19.3% between 100 and 299 retweets, although it only made up 9.1% of the total sample. In any case, the following items with more significant interaction (political events and voting mobilisation) align with the leaders’ agenda on Twitter. However, “events” has 40.7% of its posts in the least attention-grabbing section.

Table 2. Degree of attention (average retweets) according to the themes (%)

|

1-49 |

50-99 |

100-299 |

300 or more |

|

|

Political change |

11.3 |

12 |

10.2 |

0 |

|

Voting mobilisation |

7.3 |

16,9 |

14,8 |

16,7 |

|

Post-election strategy |

3.3 |

4.2 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Political events |

40.7 |

15.5 |

10.2 |

33.3 |

|

Economy/industry |

6.7 |

20.4 |

5.7 |

0 |

|

Public services |

10 |

9.2 |

6.8 |

0 |

|

Covid-19 |

3.3 |

7.7 |

19.3 |

33.3 |

|

Galicia |

4 |

6.3 |

13.6 |

16.7 |

|

Others |

13.3 |

7.7 |

6.7 |

0 |

Source: created by the author (results of greater interest in bold)

The average number of retweets enables us to determine that the coronavirus has managed to alter the campaign’s thematic organisation, as Covid-19 emerged as the most attention-grabbing topic on Twitter. As mentioned above, the elections did not occur in a usual context, so we should be wary of the results and carry out comparative studies with post-pandemic elections.

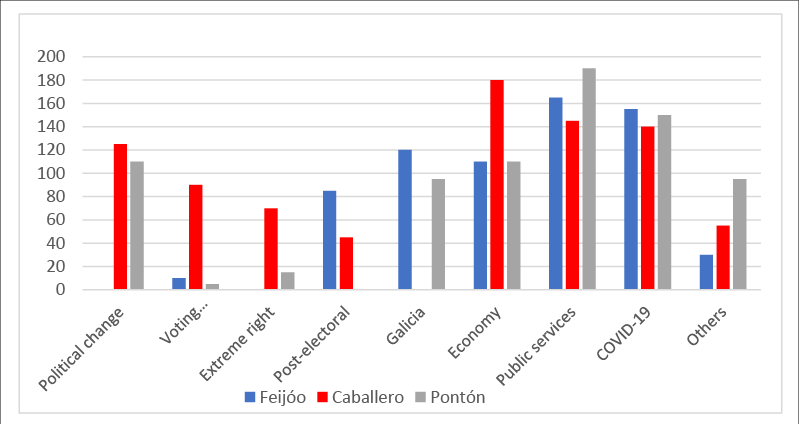

Regarding the only electoral debate with the three candidates in the running, the distribution of topics in seconds is shown in graph 1. It is important to note that only the thematic contributions are categorised; reactions to the opposition and the responses that have no relation to public policy or campaign issues are omitted.

Graph 1. Themes addressed by each candidate in the television debate (seconds)

Source: created by the author

The participating parties agreed with Television de Galicia on four major themes for the debate: Covid-19, the economy, social policies, and governance. This focus on pre-established issues is substantially different from Twitter, explaining why the election debate agenda was more programmatic. Public services and the economy were referenced several times by the three candidates in the debate.

On the other hand, it is important to note the opposition parties’ numerous seconds dedicated to political change (PSdG and BNG). This is logical given their goal to become the president of the Galician regional government. Núñez Feijóo is the candidate who most often refers to post-electoral strategies, criticising potential pacts, and emphasises that Galicia itself is a particular issue. The campaign slogan was “Galicia, Galicia, Galicia”. Quantitatively, the popular candidate participated less in the debate, a total of 140 seconds below his two primary opponents. The perception of the television performance influences the vote (Lagares Díez et al., 2020) and could have contributed to the opposition’s more proactive position, while the leader of the government needs less time to present his ideas.

4.2. Informative treatment in the reference press

We show the thematic distribution of the 296 journalistic items analysed to understand the media agenda of the elections. They are found in essential media that can establish the public discussion in Galicia (table 3). We studied 77 texts from La Voz de Galicia, 101 from Faro de Vigo, 66 from El Progreso de Lugo and 52 from El Correo de Gallego.

Table 3. Distribution of topics by a newspaper (%)

|

La Voz de Galicia |

Faro de Vigo |

El Progreso de Lugo |

El Correo Gallego |

Total |

|

|

Political chanage |

7.8 |

14.9 |

6.1 |

7.7 |

9.8 |

|

Voting mobilisation |

19.5 |

10.9 |

7.6 |

28.8 |

15.5 |

|

Post election strategy |

26 |

15.8 |

28.8 |

25 |

23 |

|

Political events |

29.6 |

16.8 |

25.8 |

19.2 |

22.6 |

|

Economy/industry |

7.8 |

13.9 |

12.1 |

7.7 |

10.8 |

|

Public services |

3.9 |

16.8 |

4.5 |

0 |

7.8 |

|

Covid-19 |

5.2 |

4 |

10.6 |

9.6 |

6.8 |

|

Others |

0 |

7 |

4.5 |

1.9 |

3.8 |

Source: Created by the author (the results of greater interest are in bold)

The category “Galicia” is not used in the media analysis as it is a theme found in others. The results indicate a preference for political events that are newsworthy, like retweets. On the other hand, the importance of the post-election strategy differs, which is a central issue for determining the future government pacts in the chosen newspapers, regardless of the editorial line. Moreover, El Correo Gallego publishes many articles on voting mobilisation, while El Faro de Vigo publishes articles on public services. The newspaper from Vigo is the one that shows the most significant plurality in the journalistic item topics.

It is also helpful for this research to determine the number of references to the parties in the newspapers. According to table 4, there is a preponderance of mixed approaches (35.1%) and those focusing on the PPdG (27.7%). There is a recurring trend in all the newspapers, although the Popular Party from Galicia in El Correo Gallego is covered extensively. This autonomous region’s political system is characterised by this party’s centrality, which is seen in its privileged location in the media.

Table 4. Party object of the information per newspaper (%)

|

La Voz de Galicia |

Faro de Vigo |

El Progreso de Lugo |

El Correo Gallego |

Total |

|

|

PPdG |

22.1 |

26.7 |

24.2 |

42.3 |

27.7 |

|

PSdG |

19.5 |

25.7 |

21.2 |

21.2 |

22.3 |

|

BNG |

15.6 |

20.8 |

15.2 |

1.9 |

14.9 |

|

Mixed |

42.9 |

26.7 |

39.4 |

34.6 |

35.1 |

Source: Created by the author (the results of greater interest are in bold)

Finally, it can be highlighted that the Faro de Vigo covers the parties to the same extent. All the categories exceed 20%, this is not the case in the rest of the newspapers, which report significantly less on the opposition parties (PSdG and BNG). The Nationalist BNG is hardly referred to in El Correo Gallego (1.9%). In this way, El Correo Gallego ignores a party that was the second most voted party in the elections, questioning the representativeness of the way it was treated journalistically.

5. Discussion and conclusion

It is worth noting that the 2020 Galician elections had many competing parties that were invited to the television debate (Ciudadanos, Vox, Galicia en Común-Anova Mareas and Marea Galeguista). Still, only three traditional parties (PPdG, PSdG, and BNG) won MPs. This apparent return to the “old politics” is linked to the fact that the political agendas on Twitter did not seem to have been affected by Covid-19. Núñez Feijóo focuses on issues that convey an image of good management, such as the economy and public services, while Caballero and Pontón allude to the need for political change. In this sense, the campaign was developed in traditional parameters and adjusted to a strong regional identity (Warf and Ferras, 2015).

In contrast to the candidates’ thematic immobility, citizens change their preferences due to the pandemic. Covid-19 is the issue that generates the most retweets. The political agenda in the electoral debate does mention the coronavirus extensively, and issues like “public services” and “economy” make up Núñez Feijóo’s themes on Twitter. It would be interesting to reflect on whether the Galician public television’s organisation of the debate- accused of manipulation by the group Defende a Galega- could have benefited the current president of the regional government by appealing to specific blocs.

Likewise, the media agenda outlined by the research indicates that PPdG receives the most attention in traditional newspapers. The political and media agendas differ in that the latter pays particular attention to the post-election strategies. Our analysis does not detect the singular reference to government pacts, in contrast to recent research that identifies the growing importance of these “meta-topics” (Rodríguez Díaz and Castromil, 2020).

To summarise, the results of the studies from the Twitter accounts, the electoral debate, and the reference newspapers provide a series of conclusions about the political and media agendas for the 2020 Galician elections. Firstly, the candidates presented a fragmented thematic agenda on Twitter, differing from the candidate in power (Núñez Feijóo) and those forming part of the opposition (Caballero and Pontón). Núñez Feijóo tweeted regarding aspects concerning the programme, such as the economy and public services. On the other hand, Caballero and Pontón prioritised messages concerning political events, change, and voting mobilisation. They aimed to promote a change to the Galician system, which is prone to absolute majorities from the PPdG.

Secondly, Covid-19 was the topic that the audience most interacted with on Twitter through retweets, followed by political events and voting mobilisation. The latter two issues were central to the leaders’ thematic agenda for this social network, but the coronavirus was not. This shows that the coronavirus was not given more importance and that the pandemic has changed the public’s interests.

Thirdly, the TV election debate revolved around Covid-19 and two programme issues: the economy and public services. The time dedicated to them was similar among all three candidates. Therefore, there is no direct correlation between the thematic agenda on Twitter and the debate on Television de Galicia. The president and candidate Núñez Feijóo is the leader who is more similar between the two.

Finally, the media agenda focused on political events and post-election strategy. The issue of the post-electoral agreements was hardly visible in the chosen media. On the other hand, the newspapers in the sample tend to focus their news items on the PPdG or mixed approaches with several parties, except Faro de Vigo, which articulate a fairly uniform coverage in quantitative terms out of the three traditional parties.

In any case, this paper is limited by the small sample size derived from the subject of study, which makes it necessary to implement future comparative research on regional elections to understand the role of Covid-19 in the 2020 elections. This study is based on the interest in determining the political agenda’s influence on the media, establishing possible correlations between the agendas. These processes could also be assessed the other way around. Isolating these public issues is complex, which fosters the need to address the thematic aspect in various discursive manifestations that yield data of interest in a hybrid communication model.

6. Acknowledgements

This article has been translated into English by Sophie Phillip.