doxa.comunicación | nº 32, pp. 75-94 | January-June of 2021

ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978

Frames of gender-based violence: a comparative study of news reports about crime with victims (1996-2016)

Encuadres de la violencia machista: estudio comparativo de las noticias sobre delitos con víctimas (1996-2016)

María Gorosarri González. Professor at the UPV/EHU. Graduate in Law (2002) and in Journalism (2004). International PhD in Communication (2011), with her thesis (in Euskara and English) “Albisteen kalitatea: Research on Basque Media’s News Quality”, financed by the Basque government (2006-2010), as well as several secondments in Humboldt Universität (Berlin, Germany) in 2009 and 2010. She has completed two post-doctoral projects: on the quality of the European press of reference (2000-2010), financed by the UPV/EHU (2012-2013), and a non-participating observation study in the editorial department of several German television channels, as a researcher at Freie Universität (Berlin, Germany), financed by the Basque government (2014-2016). Her lines of research are the feminist perspective in journalism, quality in the news and media in minority European languages.

How to cite this article:

Gorosarri González, M. (2021). Frames of gender-based violence: a comparative study of news reports about crime with victims (1996-2016). Doxa Comunicación, 32, pp. 75-94.

Received: 05/10/2020 - Accepted: 27/04/2021

Early access: 25/05/2021 - Published: 14/06/2021

Abstract:

This paper analyses the treatment of news about crimes with victims in the two newspapers of reference in Spain, El País and El Mundo. Employing the theory of framing, through content analysis, four common frames are examined, due to their considerable impact on the social consideration of gender-based violence: more detailed identification of the accuser than of the perpetrator, construction of the racial otherness of the perpetrator, explicit attribution of responsibility for the crime, and the lessening of the accuser’s credibility, determined by repetition of the term ‘alleged’ (Berganza, 2003; Carbadillo, 2010; Easteal, Holland & Judd, 2015, Escribano, 2014). The significance of these four frames in news about violence against women will be compared for the first time with other crimes with victims and which require that victim to file a complaint (terrorism, hate crimes, workplace accidents, road safety, crimes against property, and non-gender specific violence). It will be shown that the more detailed identification of the accuser, the racial otherness of the perpetrator and the lessening of the accuser’s credibility are specific frames for violence against women. Finally, the temporal analysis (1996-2006) will demonstrate that this was accentuated after the passing of Equal Rights legislation.

Keywords:

Violence against women; gender-based violence; alleged; framing; crime.

Recibido: 05/10/2020 - Aceptado: 27/04/2021

En edición: 25/05/2021 - Publicado: 14/06/2021

Resumen:

Este artículo analiza el tratamiento de los delitos con víctimas en los dos periódicos de referencia en España, El País y El Mundo. Siguiendo la teoría del enfoque (‘framing’), mediante el análisis de contenido, se medirán cuatro encuadres habituales que inciden en la consideración social de la violencia machista: identificación más detallada de la denunciante que del agresor, construcción de la alteridad racial del agresor, atribución explícita de responsabilidad en el delito sufrido y menoscabo de la credibilidad de la denunciante, condicionado a la reiteración del término ‘presunto’ (Berganza, 2003; Carbadillo, 2010; Easteal, Holland y Judd, 2015; Escribano, 2014). Se comparará por primera vez el alcance de esos cuatro encuadres en violencias machistas con otros delitos que causan víctimas y necesitan de la denuncia de éstas (terrorismo, delitos de odio, siniestralidad laboral, seguridad vial, delitos contra la propiedad y violencia contra las personas sin componente de género). Se probará que la identificación más detallada de la denunciante, la alteridad racial del agresor y el menoscabo de la credibilidad de la denunciante son encuadres específicos a las violencias contra las mujeres. El estudio temporal (1996-2016) evidenciará, además, que se acentúan tras la aprobación de la legislación sobre igualdad.

Palabras clave:

Violencia contra las mujeres; violencia de género; presunto; framing; delitos.

1. Introduction, latest studies and objective of the study

The media focus their social function on explaining reality, directing their attention towards those events which they consider to be relevant. They describe this reality through narratives which organise their discourse, called ‘frames’. These “interpretive guides” (McCombs, 2006: 87-99) or “guides of knowledge relative to a determined subject or problem” (Carbadillo, 2010: 221-224) orientate the audience’s perception of the occurrence. Journalistic activity in itself constitutes a process of drawing up frames, as the analysis of reality implies the “creation of meanings” (Escribano, 2014: 19). All this has an impact on the social consideration of these questions, especially over the long term.

Ardèvol-Abreu sets apart the frame of intention in the selection of news (‘agenda setting’), pointing out that this determines what is news, while the frame is focused on “the way in which the subject or event is described, as well as the interpretive guide that has been activated to process it” (2015: 427). Thus, the media and their public share “a common context of symbolic meanings” and, via these guides transmitted through the news, how that social reality is interpreted (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015: 429; Giménez & Berganza, 2009: 61).

The creation of these frames is a process in which the media select certain attributes from the information about certain news items. This process is called ‘frame building’ and transmits how the media have chosen to evaluate the subject (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015: 425-426). The study of these frames seeks to “capture the latent effects” exercised by the media on the definition of social reality (Carbadillo, 2010: 217-220). Therefore, the media and their journalistic expression shape the consideration of gender-based violence which is shared with society.

1.1. Common frames in news about violence against women

Academic study of media frames has taken two forms. The inductive form analyses a part of the whole sample and identifies certain frames concerning the object of study. The deductive form, on the other hand, begins by selecting the frames to be considered and studies their scope (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015: 434-435).

Research into news about violence against women has identified several frames that influence the fact that the phenomenon is not considered a “social problem”, such as the episodic treatment of such crimes and their consideration as events (Berganza, 2003: 9-10). Four other common frames focus on the figure of the perpetrator and the victim, more detailed identification of the accuser than the aggressor, the construction of the racial otherness of the perpetrator, the specific attribution of responsibility for the crime and the lessening of the accuser’s credibility (Easteal, Holland & Judd, 2015: 111).

Firstly, the media explain who the subject of the news item is. The different characterizations of the perpetrator and the victim reveals the matter of the unnecessary identification of the person attacked, not to draw attention to her but to the aggressors (Escribano, 2014: 73-78). Similarly, it has been noted that women are identified by their familial relations (De Frutos, 2015).

Nevertheless, the law does not impede the presentation of identifying details or photographs of the person arrested, providing the presumption of innocence is respected. However, it is the media themselves who self-censure and prefer to use initials, especially for crimes of greater social stigma (El País, 2014: 28).

Secondly, the frame concerning the construction of the perpetrator’s racial otherness is based on the belief that violence towards women is a migrated problem. Such otherness has turned into an image of immigrant men as a certain type of violent criminal: “rapists, paedophiles and murderers of innocent, law-abiding citizens” (De Noronha, 2018: 353). Therefore, it is not recommended to specify the aggressor’s origin, unless it is relevant (El Mundo, 2002: 68). This frame is measurable taking the data on the accuser and the accused’s nationality, origin and/or religion into consideration. Academic study has shown precisely that crimes which include such data appear in the media with disproportionate frequency (Carbadillo, 2010: 309-316; Sutherland et al., 2016).

Thirdly, attributing responsibility for the crime to the victim or the aggressor allows for identification of the phenomenon known as ‘victim blaming’, that is, the explicit or implicit attribution of responsibility for the crime to the victim herself, for example, asking whether gender violence had been reported prior to the victim being killed by a man (Peris Vidal, 2016: 1131-1132). Indirectly, justifying, annulling, or mitigating the aggressor’s responsibility due to emotional matters or derangement caused by drugs has repercussions in directing blame towards the victim, as does the presentation of the aggressor in a de-humanised way, as someone sick (Escribano, 2014: 73-78; Tiscareño & Miranda, 2020: 54-56). Due to all this, it is considered appropriate to include information concerning the aggressor’s criminal record, or as required by RTVE (the Spanish public broadcaster), of any protective measures in place, as these two points could point to any responsibility of the State for the protection of its citizens’ lives (Sutherland et al., 2016).

Finally, the fourth frame alludes to the lessening of the accuser’s credibility. In the case of violence towards women, the persecution of such crimes requires the prior reporting of the fact, normally by the woman affected, who is the one who initiates the process. In many of the cases reported, the woman’s testimony is the principal evidence against the accused. The discrediting of the victim’s account is performed by the use of certain expressions, such as the use of the term ‘alleged’ (Easteal et al., 2015: 109). Although the extent of its use has not been studied, tangentially, its excessive presence has been detected: seven times in one “three-hundred word” news item about sexual harassment (Judd & Easteal, 2013: 17).

This study seeks to fill a void in the research: the comparative study of the four frames in news items about violence against women and in pieces about all other crimes in the Spanish Penal Code which require the victim to report the crime. The scope of the fourth frame will also be analysed, although this has not previously been studied, that which deals with the degree of credibility given in the news to the victim’s testimony. The presumption of innocence is a fundamental right enshrined in article 24.2 of the Spanish Constitution, “being a general principle underpinning the legal mind in order to preserve the impartiality of the judge” (Nieva, 2016). Academe has criticized the excessive use of the term “alleged”, underlining that there is no presumption of guilt, but only of innocence. On this point, RTVE recommends the use of the term ‘suspect’:

“The presumption of innocence supposes that an individual is innocent until a judicial sentence declares his/her guilt. If a murder is committed and the police detain someone, in saying “alleged murderer” we are saying that the person is guilty unless his/her innocence is proven. Moreover, such a form of speech leads public opinion to socially condemn the detainee before he/she has been judged. For this reason, we suggest the use of “suspect” (RTVE, 2008).

Prioritizing the term ‘supposed’ over ‘alleged’ is an old question in the Spanish media. Back in 1998, Francisco Gor, Press Ombudsman in El País, wrote:

“The term «alleged» has taken on a substantive character in journalistic language, to designate those who, not having been condemned by a judge, are considered little less than to be in a waiting room in anticipation of an inexorable sentence, obviously condemnatory (…) From the legal viewpoint, there can be no doubt of the inadmissibility of applying the term ‘alleged’ to a reality or circumstance other than that of the innocence of the individual being processed (…) On applying ‘alleged’ to the perpetrator of a crime we are saying the opposite to what we intend: there are no alleged murderers, only apparent murderers presumed innocent until the sentence is firm. The journalistic success of the expression, transposed directly from the constitutional phrase of the presumption of innocence, has incorporated it into our language (…).” (Gor, 1998).

In fact, the incorrect utilisation of the term ‘alleged’ in the media as a synonym of ‘supposed’ gave rise to its inclusion in the dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy (RAE) from its 22nd edition in 2001, in reference to an accused person who has not yet been condemned. However, this reference was eliminated in 2014 (Fundeú, 2016). Therefore, traditionally, ‘alleged’ has not always been considered to be a synonym of ‘supposed’:

“«Alleged» designates one who is considered as the possible perpetrator of a crime, once legal proceedings have been originated, but no sentence has yet been delivered, and ‘supposed’ is employed when there are indications of criminality, but legal proceedings have not commenced” (Fundéu, 2011).

On these lines, RTVE recommends the use of ‘alleged’ for those who are being investigated:

“Alleged and supposed: a person is a «supposed» delinquent when there are indications of criminality, but legal proceedings have not started. On the other hand, “alleged” should be employed when, as there is a presumption of criminality, the legal process has begun, but sentencing has not taken place” (RTVE, 2008).

However, ‘possible’ is not seen as a synonym (‘possible homicide’). Following the recommendations of the El País Press Ombudsman, the media can refer to the accused (‘encausado’, since the Reform of the Law of Criminal Procedure in 2015) depending on the phase of the legal process (Gor, 1998). Similarly, El País (2014: 444) and RTVE (2018) stipulate the use of the corresponding procedural figures. Legal studies also suggest the appropriateness of indicating responsibility in accordance with the phase of the procedure:

“Hard reality seems to insist on demonstrating, therefore, that between the binary code recognised by the Constitution, of «innocent» or «guilty» –following final judgement–, there would seem to be a third way which follows a long route from ‘suspect’ to ‘accused’ passing by ‘defendant’ (…)” (Sánchez-Vera, 2012: 35).

Despite this, journalistic habit has imposed itself and recently ‘alleged’ has become a synonym of ‘supposed’ (Fundéu, 2016). At the same time, the extension of the term’s use has brought about a new and incorrect way of utilising it in the media, employing it even on those occasions when no subject has been identified and therefore there is no one to whom the crime can be attributed: “Police are searching for the alleged [sic] killer of the woman and minor in Alcobendas” (ABC, 02/05/2017). Or even, when the perpetrator has been condemned: “The High Court of Bizkaia has condemned the ex-teacher of Gaztelueta school accused of alleged [sic] sexual crimes, to eleven years in prison (Eldiario.es, 15/11/2018). Consequently, the presumption of dishonesty in women’s reporting of crime shows the lessening of their credibility. The term ‘alleged’ is applied as a doubt concerning the accuser: “The alleged [sic] victim of the gang rape during the 2016 Running of the Bulls gave evidence in court yesterday” (El Correo, 15/11/2017). This mala praxis has been termed ‘allegitis’ (Gorosarri, 2016).

In fact, according to the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court (SC), “the media is obligated to emit correct information”. The SC differentiates between truthfulness and the truth, “as the latter requires the verification of the evidence, a responsibility which transcends that required of a journalist” (CGPJ, 2017). Journalistic investigation only allows for the recounting of reported acts or the revealing of unjust behaviour, without being able to define them as crimes. Therefore, truthful information informs about an accusation, without casting aspersions on the truth of the accusation –a doubt implicit in the expression ‘alleged rape’-, unless the journalist has evidence of the falseness of the accusation or the reported facts. The right to true information takes precedent over the individual’s right to oblivion. The Supreme Court has rejected the demand of a right to oblivion of a man cleared of a double murder, as the information concerning the court case, as well as a photograph published during the hearing, are “true” and obtained in the course of “a newsworthy event” (CGPJ, 2017).

As a consequence, the degree of credibility given by the media to those who report gender-based violence is measurable by counting the frequency of the expression ‘alleged perpetrator’, ‘alleged crime’ or even, ‘alleged victim’ and comparing that to the media’s treatment of the different types of offences to be judged following a complaint by the victim.

1.2. Objective and research questions

In summary, there are four frames in the news that serve to shape the social consideration of the perpetrator and of the victim of violence against women: the more detailed identification of the victim than of the aggressor, the aggressor’s racial otherness, the explicit attribution of responsibility and the lessening of the victim’s credibility. This study intends to measure for the first time the magnitude of these four frames, from the frequency of the utilisation of the word ‘alleged’.

In order to consider if these four frames are specific to information about violence against women, their use in other crime news must be taken into consideration. Such a comparative study implies analysing those crimes investigated following a complaint by the victim. Therefore, this paper will analyse the media’s treatment of other crimes against persons or property, according to the Spanish Penal Code, which are also based on a complaint by the victim. Thus, we can ascertain if the Spanish media inform with the same professionalism when reporting on violence against women as they do on non-gender specific crime.

The objective that has guided this paper is the following: to investigate if there are specific frames for news about violence against women which differ from the media’s treatment of other crimes with victims. Based on previous research, this study intends to measure the differences in the more detailed identification of the victim than the aggressor, the construction of the racial otherness of the aggressor, the explicit attribution of responsibility for the crime and the lessening of the victim’s credibility, by comparing news items on violence against women with other media reports on crimes with victims (Berganza, 2003; Carbadillo, 2010; Easteal et al., 2015: 111; Escribano, 2014).

In order to meet the objective of the study, the following research questions (RQ) have been formulated:

- RQ1: Do the media offer more detailed identification of female victims than of male ones?

- RQ2: Does the news identify foreign aggressors in greater detail?

- RQ3: Did the passing of equal rights legislation eliminate the justification of aggressors?

- RQ4: Do the media discredit victims’ testimonies with the incorrect use of the term ‘alleged’?

- RQ5: Did the passing of equal rights legislation produce any change in how violence against women is reported on?

2. Methodology

The four frames proposed are to be studied using content analysis, a research technique that makes the classification and evaluation of “manifest and latent content” of media material valid and replicable (Krippendorf, 2018: 24). Previous research relative to the framing of news on violence against women has also employed this research technique (McManus & Dorfman, 2005; Marín, Armentia & Caminos, 2011).

The news in the editions which make up our random sample, based on the technique of the composite week, have been classified by the category of crimes against persons and property: gender violence (GV), non-domestic violence against women, sexual aggression, terrorism, workplace accidents, road safety, crimes against property and others. Firstly, the category of gender violence determines the scope of the application of the 2004 Law on Gender Violence (LOGV), that is, violent acts committed against a woman by a man with whom she has or has had a sentimental relationship. Secondly, non-domestic violence against women refers to gender-based violence when there has not been a sentimental relationship between perpetrator and victim. In this way, those cases of violence against women which are not covered by the 2004 LOGV, lacking the element of affection between victim and victimizer, are included. Thirdly, sexual aggression has been analysed as an independent category. Together these three categories make up gender-based violence or violence against women, alluding to the plurality and diversity of this violence (Zurbano Berenguer, 2018: 84-85). Fourthly, terrorism includes news about terrorist organisations. Fifthly, crimes of hate refers to aggression against members of the LGTBI collective or from other races Sixthly, workplace accidents covers accidents at work. Seventhly, road safety categorizes traffic accidents in which two people are involved, the figures of victim and victimizer being essential for the purposes of this paper. In this sense, in eighth place, crimes against property will only be analysed when the victim of the crime is an individual who needs to report the crime and not citizens in general, thus excluding crimes of political or financial corruption. Finally, news about crime that could include both figures (victim and victimizer) and which do not fit in the previous categories will be catalogued as “other”.

For the compilation of data, an analysis sheet has been drawn up (Table 1) in which the type of crime with victim is specified for each news item. Furthermore, data relative to the journalist responsible for the item is indicated. The next step is to analyse the news item in relation with the four frames chosen. For practical reasons, the different characterisations of perpetrator and victim (which reveals which the media considers newsworthy) will also indicate if the identification of the aggressor has specified his racial otherness (Carbadillo, 2010: 309-316; Escribano, 2014: 73-78; Sutherland et al., 2016).

The next step is to compile data corresponding to the attribution of responsibility, if applicable. The news item will be understood to explicitly attribute responsibility to the victim when the question of her previous reporting of violence to the authorities is mentioned. Information on the aggressor’s criminal record will denote his intentionality as well as denoting the State’s negligence in preventing the crime. Similarly, the mention of protective measures indicates social belligerence by the media concerning legal protective measures for women’s rights. Finally, justification of the event, with references to alcohol, jealousy, illness, etc.… will be taken to imply the episodic nature of the violence and not, as the 2004 LOGV has it, “the most brutal symbol of the inequality that exists in our society” (Peris Vidal, 2016: 1131-1132).

Finally, the degree of credibility given to the victim by the media is measured by counting the terms ‘alleged’ and ‘supposed’ in the news item (Easteal et al., 2015: 109). It is made clear if it refers to the aggressor (correct use), to the victim (mala praxis) or to the crime (incorrect use).

Table 1. Analysis sheet created

|

GENERAL DATA |

|

|

ID code |

|

|

Date |

|

|

Type of crime |

Gender violence, Non-domestic gender-based violence, Sexual aggression, Terrorism, Hate crime, Workplace accidents, Road safety, Crime against property, Other crimes against persons. |

|

Origin of the news item |

Event, Complaint, Declarations, Other. |

|

Title |

|

|

Journalist |

Man, Woman, Initials, Agencies, media outlet, Other media, No by-line. |

|

CHARACTERIZATION |

|

|

Perpetrator |

Data of the 1st identification. |

|

Data offered: Name & surname(s), Sex, Age, Criminal behaviour, Legal procedure, Profession, Relation, Social activity, Origin, Religion, Race. |

|

|

Valuation: Positive, Neutral, Negative. |

|

|

Victim |

Data of the 1st identification. |

|

Data offered: Name & surname(s), Sex, Age, Criminal behaviour, Legal procedure, Profession, Relation, Social activity, Origin, Religion, Race. |

|

|

Valuation: Positive, Neutral, Negative. |

|

|

ATTRIBUTION OF RESPONSIBILITY |

|

|

Question about the complaint, Question about antecedents, Question about protective measures, Justification (alcohol, jealousy, etc.). |

|

|

DEGREE OF CREDIBILITY |

|

|

Alleged, supposed |

Perpetrator. |

|

Alleged, supposed |

Victim. |

|

Alleged, supposed |

Crime. |

|

Allegedly, supposedly. |

|

Source: created by the author

To ensure that the codification meets with academic norms, the reliability of the analysis sheet has been confirmed. Despite being compiled by a single researcher, the intra-codifying reliability must be proven. Therefore, after analysing 38 news items (10.19% of the sample), on two occasions, with a fifteen-day interval between the two codifications, the Holsti formula which measures the degree of coincidence in codified decisions, also called simple accordance, gives a result of 99.2% reliability. Moreover, two external codifiers analysed 20 news items (5.36% of the sample). The intra-codifying reliability found was 98.65%, greater than the 90% required (Lacy et al., 2015: 792-796).

The corpus of analysis of this paper is made up from the two most widely sold Spanish newspapers (El País and El Mundo) over the last 20 years, that is, from 1996 to 2016. This period is ideal for the analysis of journalistic tendencies regarding the reporting of violence against women. In the first place, the sample begins in the years of the introduction of the 1995 Penal Code. Moreover, it covers the legislative changes concerning equality made in December 2004 (Constitutional Law on Integral Protective Measures against Gender Violence –hereinafter, LOGV–) and in March 2007 (Constitutional Law on the Effective Equality of Men and Women), as half of the sample is from before these changes and half after them.

The random sample is made up of 42 editions (seven editions from each year analysed) of each newspaper, that is, 84 copies (two newspapers). News items referring to crimes with victims, as defined by the Spanish Penal Code, have been selected from each copy. Thus, the sample for this study is composed of 373 news items, 205 from El País and 168 from El Mundo. Therefore, the unit of analysis for the study is the news item. All the selected news items have been studied using the content analysis method. Deductive analysis has been utilised for the empiric measurement of the media frames, that is, the four frames to be studied had been pre-selected.

Previous studies have shown that the composite week is the most efficient sample in terms of costs and the most objective for analysing daily newspapers (Lacy et al., 2001). Moreover, for observing tendencies over a period of time, the sample must respect a constant interval (Luke et al., 2011). In this case, the interval of the sample is four years. Therefore, we analyse a composite week every four years over the period included in the sample, corresponding to the following years: 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, 2012 y 2016.

Finally, studies of the number of units necessary in a sample have demonstrated that six composite weeks offers precise data, whatever the size of the corpus to be analysed (Luke et al., 2011). Therefore, this study analyses a total of six composite weeks from each newspaper over the period mentioned above.

3. Results

News items concerning offences committed by one person with consequences for another person or his/her goods constitute 4.48% of the news published in El País and 3.67%, in El Mundo, over the period analysed. The most numerous are those relating to terrorist attacks (1.46% in El País and 1.04% in El Mundo) and those about violence against women –gender violence, non-domestic gender-based violence and sexual aggression– (1,.33% in El País and 1% in El Mundo). Violence against women does not take the numerical lead until 2016, as news on terrorism decreased. In second place, we find news items about bodily harm unrelated to gender or ideology (0.75% and 0.85%). Finally, crimes against property (0.32% and 0.27%) are more common than those of road safety (0.27% and 0.21%) or workplace accidents (0.26% and 0.21%).

Taking into consideration that 13.86% of news items about crimes with victims in El País and 43.24% in El Mundo have no by-line, those accredited to journalists represent only 54.99%. We found that male journalists put their names to more items than females do (26.1% and 16.78%, respectively). Male journalists are more prominent in all crime news except road safety, where by-lines of females are over twice as common. Since 2008, the number of news items written by female journalists concerning gender violence and non-domestic gender-based violence has decreased, at the same time as the number of items on sexual aggression and other violence against persons written by male journalists has increased.

News items written by female journalists are proportionally more frequent in the local news section, where traffic accidents feature, while news about violence against women (gender violence, non-domestic gender-based violence, and sexual aggression), in the society section, chiefly present a news initiative from outside the editorial office (35.835%) or have a man’s by-line (31.28%) with reporting by women being less frequent (21.29%).

For the analysis of the different characterization of perpetrator and victim presented by the media, we focus on the data offered by the newspapers. Almost a quarter of the news items about crimes whose victims are not only women do not mention the perpetrator in the headline. But for violence against women only 12.26% fail to mention the perpetrator. Thus, the aggressor is referred to with greater frequency for crimes of violence against women and the data with which he is initially identified by the media is the relationship between the aggressor and the victim (14.23%) –sentimental, familial, neighbour, friend, co-worker, commercial…–. On the other hand, for other offences, the first data about the perpetrator is social (21.94%) –profession, social activism, etc.–; for example: “A footballer has been arrested in Cádiz for assaulting his wife” (El País, 05/06/2008).

Depending on the type of crime, the media tend to present the perpetrator with different characteristics. Criminal behaviour is utilised for the initial identification of the perpetrator of crimes against property (41.19%) and of terrorism (25.33%), for example: “Two thieves injure 20 in crash during car chase” (El Mundo, 23/07/2004). Non-domestic gender-based violence is the offence which most frequently identifies the perpetrator by name (12.94%) and, on the contrary, gender is the essential identifying feature in news about gender violence (“a man”) in 31.77% of the news items. Identification by the aggressor’s gender for other crimes represents, on average, 3.75%. Although, for the classification of an offence as gender violence, a sentimental relationship between the aggressor and the victim is a pre-requisite, the initial identification of the aggressor in cases of gender violence by his sex is ten times more frequent than for other crimes.

The perpetrator’s origin is only the first identifying feature in violence against women (4.83%) –especially, in cases of sexual aggression (11.54%), although this tendency has decreased since 2008-, as opposed to 0.74% for other crimes. That is, the perpetrator is initially identified by their origin four times more commonly than for other offences, and for sexual aggression, up to ten time more.

Turning to the totality of the details given by the media about a perpetrator, news items about violence against women give more details about the aggressor than for other crimes. Specifically, data on the perpetrator’s identity is revealed twice as often as for other crimes, although since 2008, this is less frequent. The relationship between perpetrator and victim is published in 16.63% of news about violence against women, including sexual aggression. (“A mayor is accused of rape: A councillor in Malaga claims to have recordings of the harassment she suffered”, El País, 25/07/2008 and “A couple have been arrested in La Palma for the sexual abuse of their mentally impaired daughter”, El Mundo, 05/06/2008). For other crimes, the relationship between perpetrator and victim is mentioned in 3.31%, five times less. On the contrary, these latter crimes prioritize the perpetrator’s social position (30.45%), far more than in news items about violence against women (11.36%). However, the perpetrator’s origin is mentioned more frequently in cases of violence against women (26.68%), although this is also an important element in the description of the perpetrator of other crimes (16.57%), though it is not the first identifying detail given about the perpetrator. Nonetheless, since 2008, news about non-domestic gender-based violence and sexual aggression has reduced by half the amount of data on the aggressors’ origins, whilst at the same time, the number of items on gender violence with this data doubled in number.

As regards the media’s presentation of victims of crime, their identifying data appears more frequently than that of their aggressors: only 13.76% of news items fail to identify the victim and 19.89%, the perpetrator. However, victims of gender violence and non-domestic gender-based violence are the ones who are most frequently identified (“The judge sets free Sara Alonso’s ex and jails her friend”, El País, 07/11/2004) and this has increased since 2008. Thus, non-domestic gender-based violence (28.83%) and terrorism (14.46%) are where the victim is most frequently identified by name, compared to 13.13% on average for all crimes. Again, violence against women stands out for presenting the victim from the first moment by her relationship with her aggressor in 30.97% of the news items (a growing tendency since 2008). It is worth mentioning that only one type of gender-based violence, gender violence, calls for a sentimental relationship between aggressor and victim. For other types of crime only 4.5% of news items refer to the relationship between victim and perpetrator to present the news, as the victim’s social situation seems to be more important (17.34%)– “Several Civil Guards have been suspended following the death of a Moroccan in Ceuta” (El Mundo, 14/04/2004)- as does their origin (11.80%)– “Columbian police do not know who kidnapped the Spaniard, Ángel Blanco” (El Mundo, 03/01/2000)-. The number of news items on gender violence that identify the victim firstly by her relationship with the perpetrator is greater than those that present the aggressor by his ties to the victim.

As for the full set of data offered by the media to identify the victim, there is more detail in news items on violence against women, mainly age (53.94%, as opposed to 28.57% for other crimes) and the relationship with the aggressor (18.13%, opposed to 3.34%), details which have become more frequent since 2008. It has been noted previously that affectivity is not a legal pre-requisite for non-domestic gender-based violence or sexual aggression. It is noteworthy that sexual aggression is the only news about violence against women which offers three times more data about the perpetrator than about the victim. However, as the victim is identified by her relationship with her aggressor, she is clearly recognizable.

Finally, the victim’s origin figures in 19.96% of news items on violence against women and in 23.38% of other crimes, which also include data on the victim’s race (3.14%) and religion (1.34%). Thus, we can see that the perpetrator’s origin is included more often than the victim’s in news items about violence against women, especially in news about sexual aggression, although this ceases to be true from 2008. On the contrary, for other crimes, it is the victim who is identified by his/her origin more frequently than the perpetrator.

Primary identification by using name(s) and surname(s) is four times commoner for victims than for aggressors in news about gender violence, especially following the passing of legislation designed to combat such offences. The same proportion can be seen in the initial presentation of the victim, identifying her by her relationship with the aggressor (“Arrested for assaulting his ex-girlfriend in Bilbao”, El País, 11/04/2012).

The perpetrator is presented in a neutral manner in those crimes whose victims are not only women with greater frequency than in news items about violence against women (82.82% and 72.56%, respectively). The perpetrator presents a positive image in 5.42% of news on violence against women, as opposed to 1.03% for other crimes. For example, payment of bail for an individual accused of four offences (human trafficking for sexual purposes, diffusion of child pornography, sexual abuse of minors & crimes against the public purse) was presented, in the lead-in to the story, by some statements of his which do not really exonerate him from the alleged offences:

“«The porn director Torbe leaves prison on bail»: «Why would I rape someone if I’ve got all the girls I want?». This is the phrase most commonly repeated by Ignacio Allende Fernández during the 193 days he has been in custody. The porn actor and producer known as Torbe was released on bail yesterday.” (El País, 06/11/2016).

It is also news items about violence against women which most frequently give (22.02% of items) a negative image of the perpetrator as opposed to 16.15% of other crimes.

“«Tortured for refusing to be a prostitute»: It is difficult to understand how her own family had no problem in selling her and her in-laws wanted to turn her into an object for making money.” (El Mundo, 02/01/2012).

The negative presentation of the aggressor in news about gender violence started following the passing of legislation to combat such crime The legislation resulted in the reporting of violence against women being the instance when the aggressor was least frequently presented in a neutral light. Almost a quarter of news items gave a negative image of the perpetrator, although this is also the area in which a positive image was most frequent.

However, the media opt for a neutral presentation of the victim in all crimes. The positive image of the victim is only apparent in crimes against property (10.48%), terrorism (7.01%) and, to a lesser degree, violence against women (4.96%). Moreover, the negative image of the victims of gender-based crimes, excluding sexual aggression, increased for the first time after 2008:

“«The Ertzaintza detain five men in 14 hours for gender-based violence»: Around 13:00, the Ertzaintza made a second arrest, after an officer noticed that a 46-year-old man, object of a restraining order, was with a woman in Ander Deuna square, in Sukarrieta. (El País, 21/02/2012).

“«An undocumented woman was detained when she filed a complaint against her partner»: officers of the Pontevedra police have detained a Colombian woman for being in Spain illegally, when she tried to report her sentimental partner for mental cruelty.” (El Mundo, 26/02/2008).

While negative representations of aggressors increased after 2008, the passing of equality legislation also led to an increase in the negative imaging of victims.

Looking at the attribution of responsibility by the media, it is noteworthy that news about crimes against property refer to the aggressor’s criminal record in 24.29% of cases, as opposed to an average of 4.52% in crime news in general. News items about gender violence are the second most common in mentioning the aggressor’s record (8.94%, twice the average for other crimes). They are the only items to make explicit the adoption or lack of protective measures (17.88%). However, news about gender violence alludes to the existence of a complaint by the victim seven times more frequently than in other news items (33.65% and 4.74%, respectively). News items about gender violence involving a partner or ex-partner are the only crimes where the media’s attribution of responsibility is directed more towards the victim than to the State (allusion to protective measures and the aggressor’s record). Since 2008, both newspapers have tripled the number of stories including the aggressor’s criminal record and doubled references to previous complaints but only El País has increased the number of mentions of protective measures.

Similarly, news about gender violence and non-domestic gender-based violence more frequently includes some justification of the events: 38.47% and 18.38%, compared to 4.31% of other crimes. It should not be forgotten that no news items concerning terrorism include any justification. Moreover, since 2008, the number of news items on gender violence which include data that tends to justify the events has increased, for example:

“«A man has been arrested in Torrevieja for slitting his partner’s throat»: The aggressor came home drunk, as he himself declared. Moments later, his partner started an argument. The man finished the quarrel by stabbing the woman in the carotid artery.” (El País, 07/01/2008).

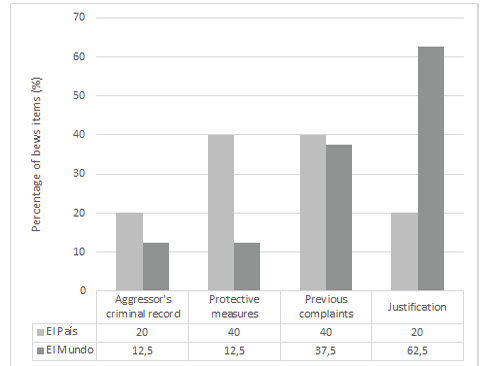

Both newspapers publish a similar number of pieces alluding to previous complaints by the victim or their lack, but graph 1 shows the differences in the attribution of responsibility following the passing of equality legislation. El País refers to State protective measures three times more often and to the aggressor’s record twice as often. El Mundo includes some justification of gender violence in over half of the relevant news items, especially the question of an argument prior to the aggression.

Graph 1. Attribution of responsibility in news about gender violence since 2008

Source: created by the author

Adding together the data from both newspapers, violence against women is the news which most commonly includes justification of the crime committed. News items on gender violence offer some sort of justification up to ten times more often than other news and non-domestic gender-based violence over four times more.

Finally, if we analyse the facts presented in news items about crime, in each article about violence against women the expressions ‘alleged’, ‘supposed’, ‘allegedly’ and ‘supposedly’ appear an average of 8.41 times: 11.57, in gender violence; 8.61, in non-domestic violence against women; and 5.06 in sexual aggression. In other crime news, such expressions are reduced by half: 4.92 times per news item. What is more, only 9.45% of the use of these expressions in news about violence against women is correct and 5.52%, in other crime. Consequently, the incorrect utilization of such expressions is almost twice as frequent in crimes of violence against women:7.62 times on average in each news item on violence against women and 4.65, in news about crimes whose victims are not only women:

“«The Ertzaintza disprove the accused’s version of the killing of his ex»: it was then that (the officers) discovered the body of C.E.B. lying lifeless on the floor by a pool of blood. She had a 20cm knife sticking out of the back of her head. The supposed [sic] perpetrator of the killing had fled”. (El País, 2012/5/31).

This tendency to employ the expressions ‘alleged’, ‘supposed’, ‘allegedly’ and ‘supposedly’ with greater frequency in news about violence against women has increased since the introduction of legislation on gender violence: the use of such expressions in news about non-domestic gender-based violence and sexual aggression is fifteen times greater and in cases of gender violence this figure rises to twenty times more since 2008, although their use has also generally increased, being ten times more common, especially for crimes against property. Again, news about gender violence as covered by Law 1/2004 shows twice the number of instances of ‘alleged’ than in other news, followed by non-domestic gender-based violence and sexual aggression. Even if we look merely at the accusation of crimes, the two newspapers analysed utilize the expressions ‘alleged offence’ or ‘supposed offence’ 7.43 times per news item in reports on violence against women (10.43, in gender violence) and only 4.62, in other crimes.

The newspapers also use different expressions to refer to the perpetrator. The commonest, grouped by types of crime, show that identification of the perpetrator depends on the crime, mainly news about terrorism (‘terrorist’: 1.77 times per item, as opposed to 0.71 in the rest). The perpetrator is named depending on the stage of the proceedings (‘detainee’, ‘accused’) to a greater degree in non-gender specific crimes of violence (1.89 times, as against 1.09 in the rest). Finally, the perpetrator is presented as ‘alleged’ followed by the term corresponding to the crime (‘aggressor’, ‘abuser’, ‘rapist’) twice as frequently in cases of violence against women (0.56 times per item and 0.21 in the rest).

The same thing happens with the accuser, who is presented as the ‘victim’ twice as commonly in news about violence against women as in other crimes: 0.95 times per item (1.7 times, in gender violence) and 0.47 per news item for other offences with victims. Not even news about terrorism includes the expression “victim” so often: only 0.3 times per news item. Again, as seen in the utilisation of the term ‘alleged’, news about violence against women supposes twice as much use of the term ‘victim’ when referring to the accuser as for other crimes.

4. Discussion

News about violence against women has always been very common, in comparison with other crimes, only exceeded by news about terrorism. However, Marín et al. highlight that the quantity of news about gender violence in the media does not coincide with a “real interest in raising awareness in society” (2011: 436). An American study in 2000 found that news items about violence without reference to gender were more numerous and longer than news about violence (McManus & Dorfman, 2005: 51). In El País, El Mundo and Catalan regional newspapers, from 2006 to 2014, news items were still short: “67% are no more than one column” (Carrasco, Corcoy & Puig, 2015: 88). This study has confirmed that since the passing of equal rights legislation, the news initiative has mainly come from outside the editorial office and there have been fewer female journalists covering these subjects since 2008 or, at least, being credited with by-lines. Regardless of the number of news items, media handling of this subject plays a fundamental role in the social consideration of violence against women.

Several studies have indicated that El País and El Mundo offer more details about the perpetrator than about the victim in news concerning violence against women (Carrasco et al., 2015: 88; Menéndez, 2014: 69). This study has quantified that the media offer twice as much data about the perpetrator of violence against women than in other crimes. Equally, the aggressor in gender-based violence even appears in the headline of the news item twice as frequently as in other crimes. The perpetrator’s origin appears as the initial identifying detail up to four times more in violence against women, especially in sexual aggression, where he is identified by his birthplace over ten times more than in other crimes. In fact, mention of the perpetrator’s origin is more frequent in violence against women, while the victim’s origin is more common in other crimes, but not in information about violence against women, though the origin of both aggressor and victim do appear in the data from agencies when both are foreigners (Rodríguez Cárcela & López Vivas, 2020: 49). Bearing in mind that other studies have found that El País is notable for not indicating “the ethnicity or nationality of those involved” (Marín et al., 2011: 462), we should consider that the journalism of the two newspapers of reference analysed in this study may be the most respectful in their handling of violence against women.

Victims of gender violence are identified with their name and surname, based on their relationship with the aggressor, in a larger number of news items than the detainee, especially since 2008. There are also more details about them than about the aggressors, particularly in news about gender violence and non-domestic gender-based violence, despite those aggressors being the ones about whom most data is given.

As a result, turning to the first frame analysed, we confirm that news about violence against women identifies the victim more frequency than is the case for other crimes. The identification of the victim is a characteristic of news about violence towards women, especially gender violence, and considerably more since the passing of the legislation that seeks to combat it. The media also typically apply the second frame in violence against women, as the details they offer about the aggressor tend to underline his racial otherness more frequently than for other crimes.

In this sense, aggressors and victims of violence against women are presented in a non-neutral manner more often than in other crime-related news. While the negative image of the aggressor is evident from 2008 onwards, that tendency corresponds with the victim also being presented in a more negative light. It is significant that the person whose integrity the legislation on equality is supposed to protect, has the worst image in the news.

This negative presentation of the victim is related to the media’s attribution of responsibility. In cases of violence against women, the aggressor’s criminal record is mentioned twice as often as in other crimes, only exceeded by crimes against property, which mention it up to three times as frequently. But, since 2008, mentions of the aggressor’s criminal record have tripled in news about violence against women. Similarly, questions relative only to gender violence, such as a previous complaint, have doubled in frequency since the relevant legislation. However, justification is almost ten times more common in gender violence than in other crimes and four times more than in non-domestic violence.

The question of the aggressor’s criminal record mitigates the numerous news items that include a justification of the events. Both indicators show a clear tendency to be included in news about violence against women. Furthermore, both have increased since the passing of laws against gender violence. Nevertheless, the question concerning previous complaints points directly at the victim and, effectively, this last question is more frequent than the two others pertaining to the aggressor. Moreover, this has grown since 2008. Even so, we understand that this is insufficient to affirm that the third frame, regarding the attribution of responsibility for the crime to the victim, is specific to news about violence against women.

Several authors consider that the presentation of the victim as weak and lacking in agency or activity implies that the media are blaming her for the situation she is experiencing (Gómez Nicolau, 2016: 197; Ménendez, 2014: 66). Not even considering the fact that women are called victims twice as often as complainants in other crimes do we share the view that this is a direct attribution of responsibility.

Finally, use of the term ‘alleged’ in news about violence against women doubles that in other news, news about gender violence regulated by the 2004 law being that which includes most examples of ‘alleged’. There has been a disproportionate increase in the use of the term since 2008, reaching ten times more usage than in other crimes. Again, the figure is doubled in gender violence, and in news about non-domestic gender-based violence and sexual aggression it is 1.5 times more frequent. The same thing happens with the denomination of the perpetrator, which includes the term ‘alleged’ twice as often in news about violence against women.

Therefore, we can see that the fourth frame concerning the lessening of the complainant’s credibility is specific to news items on violence against women, in presenting a negative image of the victim and sowing doubts about the truthfulness of her testimony, employing the terms ‘alleged’ and ‘possible’ twice as frequently, both in the account of the event and in the identification of the aggressor. Even the incorrect expression ‘alleged crime’ is twice as common when speaking of violence against women than in other crimes. Furthermore, this tendency has become more blatant since the passing of laws on equality.

It is clearly demonstrated that news concerning violence against women does indeed have specific frames (more detailed identification of the victim than the aggressor, construction of racial otherness of the aggressor and the lessening of the victim’s credibility). The media maintain an ambivalent position with respect to the attribution of responsibility for the crime to the victim or the aggressor.

What is more, following the passing of the law on gender violence, a reaction was triggered in the media towards those who filed complaints about violence against women, this being even more virulent in those cases of gender violence contemplated in the law. The media offers a worse image of these victims, whilst at the same time there is an increase in the information that lessens their credibility. The discrediting of the complainant’s testimony acts as gender-based resistance to the advance of legislation on equality and has a direct effect on the social consideration of violence against women. This is the version that is to guide society in its reflection on the right to a violence-free life, for women as well.

5. Bibliographic references

Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2015). Framing o teoría del encuadre en comunicación. Orígenes, desarrollo y panorama actual en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 70, 423-450. Disponible en http://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2015-1053

Berganza, M.R. (2003). La construcción mediática de la violencia contra las mujeres desde la Teoría del Enfoque. Comunicación y Sociedad, 16 (2), 9-32. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.15581/003.16.2.9-32

Carbadillo, P.C. (2010). El proceso de construcción de la violencia contra las mujeres: Medios de comunicación y movimiento feminista. Una aproximación desde la teoría del framing. (Tesis doctoral). Universitat Jaume I, España. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3bSvqEQ

Carrasco Rocamora, M., Corcoy Rius, M., Puig Mollet, M. (2015). El tratamiento de la violencia machista en la prensa de información general catalana. Estudio de dos casos mediáticos y su repercusión en la prensa local. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo, 2, 77-92. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.15304/ricd.1.2.247

Consejo General del Poder Judicial (CGPJ) (2017). Memoria anual (correspondiente al ejercicio 2016). Disponible en https://bit.ly/3cyEBt4

De Frutos, R.A. (2015). Mediciones e índices de evaluación inclusivos: Examen de los indicadores de género y medios de comunicación. Cuadernos artesanos de comunicación, 86, 101-130. Disponible en http://doi.org/10.4185/cac86

De Noronha, L. (2018). The Figure of the ‘Foreign Criminal’: Race, Gender and the FNP. En M. Bhatia et al. (eds.), Media, Crime and Racism (pp. 337-354), Palgrave Studies in Crime, Media and Culture. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71776-0_17

Easteal, P., Holland, K., y Judd, K. (2015). Enduring themes and silences in media portrayals of violence against women. Women’s Studies International Forum, 48, 103–113. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.10.015

Escribano, M.I. (2014). Encuadres de la violencia de género en la prensa escrita y digital, nacional y regional. La Verdad, La Opinión, El Mundo y El País desde la teoría del framing (2005-2010). Murcia: Universidad de Murcia. Tesis doctoral. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3eKcfPb

El Mundo (2002). Libro de Estilo. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3vyNkE8

El País (2014). Libro de Estilo, Santillana: Madrid.

Fundéu BBVA (29 de julio de 2016). ‘Presunto’ es sinónimo de ‘supuesto’, Recomendaciones. Disponible en http://www.fundeu.es

Fundéu BBVA (13 de octubre de 2011). ‘Al parecer’ o ‘presunto’, pero no ‘al parecer presunto’, Recomendaciones. Disponible en http://www.fundeu.es

Giménez, P. y Berganza, M.R. (2009). Género y medios de comunicación. Un análisis desde la objetividad y la teoría del ‘framing’. Madrid: Editorial Fragua.

Gómez Nicolau, E. (2016). Culpabilización de las victims y reconocimiento: límites del discurso mediático sobre la violencia de género. Feminismo/s, 27, pp. 197-218. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.14198/fem.2016.27.11

Gor, F. (22 de marzo de 1998). ¿Presunto? Mejor, supuesto. El País. Disponible en https://bit.ly/2NoyxLf

Gorosarri, M. (24 de mayo de 2016). “Presuntitis”: Los medios y las denuncias falsas. +Pikara y Eldiario.es. Disponible en: https://bit.ly/3eCEIF4

Judd, K., Easteal, P. (2013). Media Reportage Of Sexual Harassment: The (In)Credible Complainant. The Denning Law Journal, 25, pp. 1-17.

Krippendorff, K. (2018): Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Los Angeles: Sage.

Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., Riffe, D. y Lovejoy, J. (2015). Issues and Best Practices in Content Analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 791–811. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015607338

Lacy, S., Riffe, D., Stoddard, S., Martin, H.y Chang, K.K. (2001). Sample Size For Newspaper Content Analysis in Multi-Year Studies. Journalism & Mass Communication Quaterly, 78(4), 836-845. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/107769900107800414

Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género. Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 313, de 29 de diciembre de 2004, 42166-42197. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3vtn7qB

Ley Orgánica 3/2007, de 22 de marzo, Para la Igualdad Efectiva de Mujeres y Hombres. Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 71, de 23 de marzo de 2007, 12611-12645. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3vsSlhE

Luke, D., Caburnay, C. y Cohen, E. (2011). How Much Is Enough? New Recommendations for Using Constructed Week Sampling in Newspaper Content Analysis of Health Stories. Communication Methods and Measures, 5(1), 76–91. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2010.547823

Marín, F., Armentia, J.I., y Caminos, J. (2011). El tratamiento informativo de las victims de violencia de género en Euskadi: Deia, El Correo, El País y Gara (2002-2009). Comunicación y Sociedad, 24(2), pp. 435-466.

McCombs, M. (2006). Estableciendo la agenda: El impacto de los medios en la opinión pública y en el conocimiento. Madrid: Grupo Planeta.

McManus, J., Dorfman, L. (2005). Functional Truth Or Sexist Distortion? Assessing A Feminist Critique Of Intimate Violence Reporting. Journalism, 6(1), pp. 43-65. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905048952

Menéndez, M.I. (2014). Retos periodísticos ante la violencia de género. El caso de la prensa local en España. Comunicacion y Sociedad (Guadalajara), 22, pp. 52-77. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3vC7xsH

Nieva Fenoll, J. (2016). La razón de ser de la presunción de inocencia: el prejuicio social de culpabilidad. InDret, 1.

Peris Vidal, M. (2016). La representación rigurosa del origen de la violencia machista en la prensa escrita: una propuesta de medición. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico, 22(2), 1123-1142. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.54255

Rodríguez Cárcela, R., López Vivas, A. (2020). Tratamiento informativo de la violencia de género: asesinatos de mujeres. Análisis de la agencia EFE. Ámbitos: Revista Internacional de Comunicación, 47, pp. 23-60. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2020.i47.02

RTVE (2008). Manual de Estilo. Disponible en https://bit.ly/3vyZCN8

Sánchez-Vera, J. (2012). Variaciones sobre la presunción de inocencia: Análisis funcional desde el derecho penal. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

Sutherland, G., McCormack, A., Easteal, P., Holland, K. y Pirkis, J. (2016). Media Guidelines For The Responsible Reporting Of Violence Against Women: A Review Of Evidence And Issues. Australian Journalism Review, 38(1), 5-17.

Tiscareño García, E. y Miranda Villanueva, O.M. (2020). Victims y victimarios de feminicidio en el lenguaje de la prensa escrita mexicana. Comunicar, 63(27), 51-60. Disponible en https://doi.org/10.3916/C63-2020-05

Zurbano Berenguer, B. (2018). Comunicación, periodismo y violencias contra las mujeres en España: Reflexiones en torno a un estado de la cuestión. Observatório, 4(2), 80-117. Disponible en http://dx.doi.org/10.20873/uft.2447-4266.2018v4n2p80

doxa.comunicación | nº 32, pp. 75-94 | January-June of 2021

ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978