1. Introduction and the State of the Art

The distribution of free content by the media since the advent of the Internet has had a major impact on the working methods of newsrooms and their funding model as well. Even at the end of the 20th century, and in the early years of the 21st, the traditional structure of newsrooms did not meet the necessary requirements to face the change that was to come, and the media business model was beginning to suffer the effects of free content and of maintaining two formats at the same time: conventional print and the emerging digital mode. At first, advertising on the Internet took the form of conventional advertising campaigns converted to a digital format in a way that was ineffective and unsightly (banners, buttons, and page-stealers, for the most part). In general, these offered very low profit margins for the medium and were unattractive for the user, which forced digital media to act quickly and look for other revenue streams outside conventional advertising in order to survive the digital transformation (Cerezo, 2017).

1.1. Change in the business model

The capability of digital media to achieve synergies between brands and the new digital content, especially in vertical or specialised portals, gradually revealed the potential of advertising as a means of financing. In a very short time, the capacity that specialisation of content on the Internet could have for brands was confirmed by allowing them to reach their target audience more directly. Likewise, advertisers very quickly grasped the opportunity that the Internet offered them to generate content and show it to their target market and potential customers as well. In the context of economic crisis, branded content became an increasingly valuable format for reformulating an advertising model that sought to connect with audiences, as well as for bringing new business opportunities to digital media.

At the same time, email facilitated a new way of distributing content on a massive scale, either with advertising or other material, while at the same time it did so in an increasingly personalised way. With the advent of Web 2.0, social networks reinforced these foundations by giving brands a direct communication channel to their customers through which they could distribute their content and interact with them as well. This ability to generate content, as well as the access provided by the Internet in allowing brands to display such content, also led to a new way of distributing advertising content through digital media by using both traditional text and image formats, in addition to audio-visual and interactive modes.

Thus, as the years passed, the potential that online content could offer to brands was being verified, as they were able to reach their target audience in a more direct and personalised way through digital media.

“The stagnation of digital advertising based on page views and traditional formats over the last decade has led the online media sector to explore new revenue streams, such as different forms of e-commerce, the sale of content and technology to third parties, events, and content marketing” (Cerezo, 2017: 47).

Cerezo himself notes in the same study that “in this scenario with the display model adrift, the media have found in sponsored content an important source of income. Native advertising designed to imitate form and function while becoming integrated as much as possible with its environment, as well as branded content (content created or sponsored by a brand), have experienced enormous growth”(2017: 37).

From the First Study of Content & Native Advertising conducted by the IAB together with its associate company, nPeople.de in 2017, it was found that 83% of advertisers “use branded content or native advertising on a regular basis in their activities. A total of 7 out of 10 combine the new formats with more traditional models, while 2 out of 10 report very intensive use” (IAB, 2019: 17). Furthermore, this study predicted that in 2018, “2 out of 3” would increase “the budget allocation for branded content and native advertising” and noted that 32% intended to maintain the same level (Ibid.). In short, experts agreed that companies would continue to increase the budget allocated to digital marketing (Carcelén, Alameda and Pintado, 2017: 1,648).

In the United States, an essay published in 2018 by the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, which resulted from a survey of 220 agency and brand professionals from 25 different countries, pointed out that two thirds of communication professionals were committed to branded content for their campaigns, while 67% planned to increase their spending and/or that of their clients on branded content in 2019 (Maister and Gretzel, 2018: 19). Along the same lines, the aforementioned First Study of Content & Native Advertising carried out by IAB Spain has stated that “6 out of 10 marketing and communication professionals claim that branded content and native advertising improve results, and see it as an interesting alternative due to market saturation” (IAB, 2019: 4).

According to the study known as Estudio de Inversión Publicitaria en Medios Digitales 2019 (Study of Advertising Investment in Digital Media), investment in digital advertising exceeded €3 billion for the first time in that same year, 2019. In this context, investment in branded content increased from €48.4 million to €71.5 million, an increase of 47.9%, while investment in native advertising increased by 15%, going from €19.3 million to €22.2 million (IAB, 2019). However, the COVID-19 crisis might reverse this trend. This has been affirmed by a report from Infoadex, a company specialising in the in-depth monitoring of advertising activity in Spain, which forecasted the fall in digital advertising investment of 14.3% for the first half of 2020 (Rivas, 2020).

In this context in which advertising in the media is becoming more prominent, and where investment in traditional advertising formats is decreasing “because such formats are perceived to be intrusive and ineffective” (Miotto and Payne, 2019: 23), and in which there is intense competition to capture the attention of audiences by both the media and brands, “companies and the media have found in branded content a new way to connect with audiences” (2019: 24). One of the media pioneers in the creation and dissemination of these types of campaigns is the New York Times. In addition to its innovative work, it has become a benchmark thanks to its successful subscription-based funding model, which by the end of 2020 had already gained 7 million subscribers (Lee, 2020).

1.2. Insecurity in the journalistic profession

Since 2008, journalism has been immersed in one of the biggest crises in its history, like so many other professions, partly due to the aforementioned clash between technology and journalism as a result of the digital transformation (Huey, Nisenholtz and Sagan, 2013). Job losses in the Spanish media industry between 2008 and 2015 affected 12,200 professionals (Palacio, 2015). During these years, economic objectives took precedence over journalistic criteria and news interests in the restructuring of newsrooms, as affirmed at that time by 54% of public media workers and 65% of private media staff (Soengas, Rodríguez and Abuín, 2014: 114).

In 2015, 75% of employed journalists acknowledged having relented to pressure in order to protect their jobs or sources of income, a figure that reached 80% among freelancers in the sector. According to the Informe de la Profesión Periodística (Journalism Profession Report) 2015, these pressures came from economic interests to an even greater extent than from political forces.

In 2018, unemployment fell for the fifth straight year since the crisis had begun, but still remained 50% higher than in 2008. One of the consequences of this decline is reflected in the growing number of journalists working as freelancers, which in 2018 accounted for a quarter of all workers in the field of journalism and communication. Moreover, 30% of the contracted employees and 50% of the self-employed workers earned less than 1,500 euros per month (Palacio, 2018). However, in September of 2019, the number of journalists officially registered as unemployed reached 7,003, which was 2.6% more than the previous year, 63% of whom were women, and 37% men (Palacio, 2019). Nevertheless, this figure is rather insignificant compared to the impact of COVID-19 in 2020, which increased the figure by 29%, according to the Journalism Profession Report of the same year, in which the main problems of these professionals were low pay, unemployment, and job insecurity, in addition to others such as the lack of media independence, as well as a shortage of rigour and impartiality (Palacio, 2020).

Due to the growing presence of brands in digital media content through branded content, native advertising, section sponsorships, and affiliate content, journalists are now responsible for writing many of these items. The main international and Spanish digital media have departments specialising in content marketing to produce these items, and have even recruited journalists as part of their teams. Specifically, in the newspaper El País, this department is called La Factoría (The Factory), which had already grown to a staff of 30 employees by April of 2018, of which a third were journalists, and there were more than 240 collaborators including writers, programmers, and experts in data analysis and social networks (Hernández, 2018). Regarding this situation, Josep Lluís Micó (2019) pointed out that if it not for this solution, these journalists would be unemployed. This same author explains that “analysts such as Donald Miller (2017) and Andy Bull (2013) praise this labour reshuffle by pointing to it as a good solution for the problem of news writers who until recently have worked in media that have been forced to lay them off, or have even been forced to close the business” (Micó, 2019: 20).

In the second decade of the 21st century, brands in the United States, and later in other countries around the world, began to create their own content marketing departments and started launching their own websites and blogs with content far removed from more corporate-oriented data, in order to disseminate information on various topics (Cartes and García, 2017). This practice sometimes falls under the umbrella of brand Journalism, which is a term increasingly used by marketing professionals, yet at the present time there has been very little research related to its appropriateness. In his article entitled, “El último desafío, el brand journalism” (The latest challenge, brand journalism), Fernando Barciela asks himself why the communication directors of multinational companies that have these departments “describe their company websites as brand journalism and not merely as content marketing sites, which would be a more accurate label. In fact, this distinction, which has nothing to do with semantics, has been generating a bitter controversy between journalists and public relations professionals, who are in antagonistic positions” (Barciela, 2013: 132-133). This same article points to highly important aspects such as the loss of credibility, the lack of independence, or the difficulty in offering impartial information.

This trend among journalists to assume functions linked to advertising, which has been driven by a change in the business model and the interest shown by brands in content, highlights the need to review the tasks carried out by journalists in digital media and to redefine professional and training profiles that meet the requirements of the new business model without affecting the duties and obligations of the essential ethics of the profession.

This need has already been pointed out in a study entitled, Las funciones inalterables del periodista ante los perfiles multimedia emergentes (The unchanging tasks of the journalist in the face of emerging multimedia roles), published in 2015, and the need still remains unaddressed to this day (Sánchez-García, Campos-Domínguez and Berrocal, 2015).

1.3. Content with a brand presence

Today, traditional forms of online advertising continue to explore how to make a stronger impact on the reader, with the added difficulty that the more they disrupt the reading experience, the more negative the opinions of consumers become. Thus, as mentioned above, it is necessary for brands to find new ways to communicate with audiences, and “sponsored content has the potential to do this” (Newman, Levy and Nielsen, 2015: 105). The same authors point out that such items must find a way to fit seamlessly into the site and be integrated into the content to improve their perception by readers, but with the risk that they can sometimes be presented in a way that is legally dubious and confusing to the reader as well. In this sense, it is necessary to review the legal framework in order to integrate these new advertising formats into the regulatory context: “Until current legislation is modified, the ratio of legal uncertainty surrounding these new non-conventional advertising formats is high, and increasing the level of caution and compliance with legal obligations is a highly advisable practice” (Ortiz, 2015: 25).

Along the same lines, it is important to point out that according to the Informe de la situación de la Profesión Periodística 2019 (Report on the State of the Journalistic Profession), disinformation is an issue of concern to 91% of Spanish people, with advertising occupying the 3rd position in this regard, preceded by people with the ability to exert influence in social networks, and the political realm. The same study reflects that 93% of journalists consider that advertising and marketing are largely responsible, or at least fairly so, in acting as a source of disinformation (Palacio, 2019: 88).

According to the IAB (Interactive Advertising Bureau), new advertising formats mainly consist of three types of commercial content: native advertising, branded content, and content from influencers (IAB, 2019: 14). However, it is not always easy to differentiate among them, and occasionally we find that the experts themselves, including media communication companies, brands, agencies, and even departments that specialise in this domain use the terms branded content, native advertising, and sponsored content interchangeably when referring to such labels, an example of which is the following: “branded content or sponsored content is experiencing rapid growth, and is a consolidated format in the main Spanish cybermedia organisations” (Tambo, 2020). Moreover, branded content can appear to be native advertising when it is integrated into paid media content, or is mistaken for sponsored content due to the fact that it is paid content.

1.3.1. Branded content

Joe Pulizzi, author of works such as Killing Marketing and Epic Content Marketing, is a leading international content marketing expert. In 2015, he defined branded content as “a strategy with a fast impact”, in which “there is no need or desire to build a relationship through content” (Pulizzi, 2015). According to the aforementioned USC Annenberg study, branded content is defined as “paid content that is created and distributed beyond traditional forms of advertising, using formats familiar to consumers, with the intention of promoting a brand, either implicitly or explicitly, through storytelling” (Maister and Gretzel, 2018: 18).

However, it can be argued that both definitions, which mention “promoting the brand” and rejecting the “desire to build a relationship through content” as objectives of branded content, are partially contradicted by definitions proposed by the Branded Content Association and the IAB, the latter of which defines it as follows:

“It is relevant, entertaining, or interesting content, with a non-advertising aspect, generated by a brand to create an audience and connect with them. The content implicitly communicates the values associated with the brand, although the brand stays in the background” (IAB, 2015: 9).

The Branded Content Marketing Association, based in London (UK), published its own definition of the term in 2016. The original text is the result of a collaborative study carried out by a team of researchers from Oxford Brookes University and the Ipsos company, based on telephone interviews with thirty leading experts from diverse areas of the marketing industry, and they define branded content as follows: “Any product fully or partially funded, or at least endorsed, by the legal owner of the brand that promotes the brand’s values and causes audiences to choose to interact with it based on a rationale of attraction due to its entertainment, informative and/or educational value” (Asmussen, Wider, Williams, Stevenson and Whitehead, 2016: 34).

The Asociación española de Branded Content (Spanish Association of Branded Content), with the help of Javier Regueira (2018), holder of a PhD in branded content from UCM, defines the term (from a translation of the original text) as follows:

“It is a communication asset (or assets), produced or co-produced by a brand which, through formats that fulfil the role of providing entertainment, information and/or utility, aims to communicate its values and connect with an audience who, upon finding it relevant, voluntarily devote their attention to it” (Regueira, 2018).

In the end, this is the definition of the term that can be read on the front page of the website of the Branded Content Marketing Association of Spain (BCMA Spain), which is the most appropriate to take into account for this study, due to its origin. In any case, the last three definitions presented insist on three fundamental, distinctive aspects of branded content: fulfilling the role of entertainment, information and utility, communicating the brand’s values, and connecting with the audience, so that they devote their attention to it voluntarily because they find the content entertaining or identify with the values it conveys.

1.3.2. Native advertising

Sometimes it is not easy to distinguish branded content from native advertising. The very definition of the latter, set out in IAB Spain’s 1st Study of Content & Native Advertising, shows similarities between the two formats:

“Native advertising is that which is integrated into the natural editorial content of the page or the functionality of the medium in which it is published, allowing the brand to be present in the publication in a more harmonious way with the rest of the content compared to other advertising systems” (2017: 7).

Both branded content and native advertising try to reach their audience in a natural and non-intrusive way, but unlike the latter, branded content should not include the product or service explicitly, but instead should generate an experience that offers information of interest to the user focused on the brand’s values, not on its products (IAB, 2019: 9). The objective of native advertising, however, is more focused on integrating itself into the medium so that the user can naturally access information about its products.

“Native advertising delivers the message in an integrated way so that the user has an experience with both the content and the medium, whereas Branded Content is a communication option that uses content to transmit the values of the brand or company in an implied way that is integrated into the story with useful and interesting information” (IAB, 2019: 9).

1.3.3. Sponsored content

Opinions differ regarding the term sponsored content as well. According to the dictionary of the Real Academia Española (RAE) (Spanish Royal Academy), the verb sponsor means “to support or finance an activity, usually for advertising purposes”. In the professional publishing and advertising environment itself, the term sponsored post or sponsored content is often used to refer to paid content, generally in the form of advertorial or infomercials, native advertising, branded content, or even ad units or widgets of recommended content that have links to external pages, or in other words, they use the term without taking into account the typology of the content.

The definition by RAE (2014) is very broad, but when talking about “financing an activity”, it clearly introduces a typology that is different from those defined above. Consequently, it is advisable to refine and differentiate it as simply another typology. In this study, sponsorships or sponsored content refer to the financing or support of a digital medium, space, section, or its editorial content by a brand, generally with the aim of increasing its visibility and/or brand image. The chosen space is usually associated with its activity or the values with which it identifies itself, or intends to identify itself. In these cases, they generally choose to simply place their logo or a text in the content, indicating that this content produced by the media outlet is sponsored by the brand, although they might provide content or information specific to the brand as well.

1.3.4. Affiliation

In recent years, digital media have started to include affiliate programmes with online shops in their content, which are used as another source of income within their business models. These texts are usually written by journalists and writers who collaborate with the media and, even though the items are not advertising in the strictest sense, they have a significant brand presence.

According to the definition established by the IAB, “the media outlets, which we call affiliates), advertise the merchants (which we call advertisers) through different channels, such as social networks, websites, etc., and obtain a commission every time the user performs a previously agreed action: registering on a certain website, making a purchase, downloading an app, etc. The paradigmatic remuneration model for this channel is therefore the Cost Per Action (CPA) format” (IAB, 2016: 2).

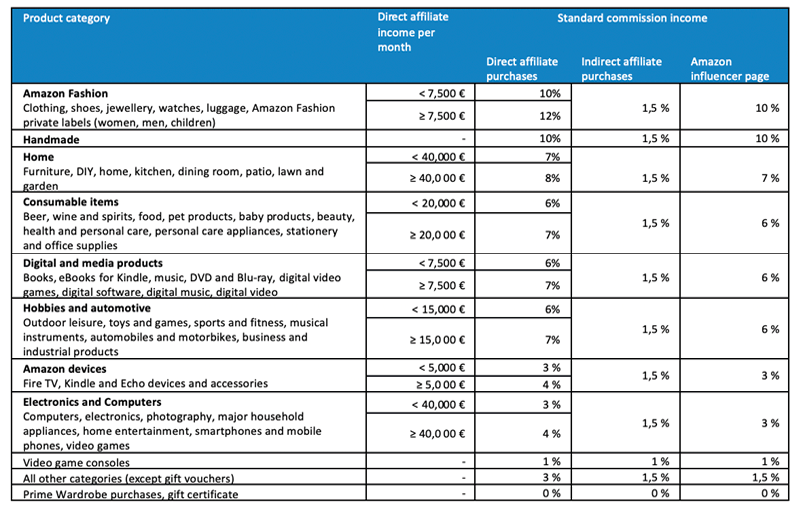

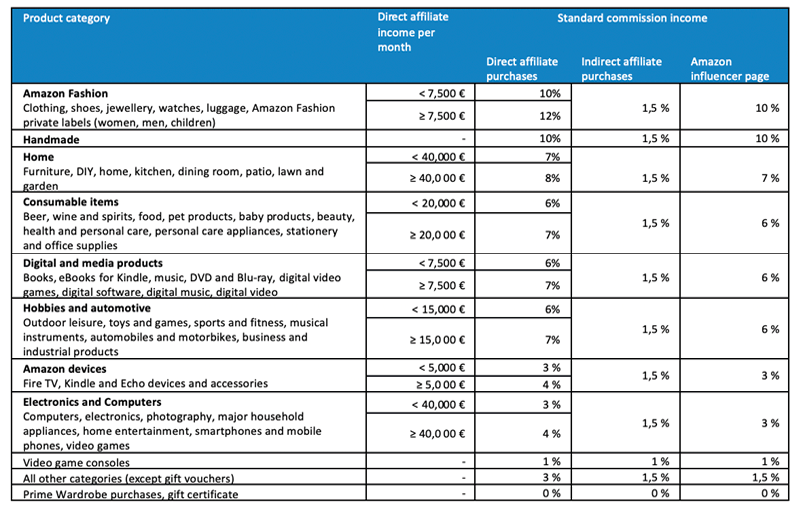

The final average commission set by companies such as Amazon is between 1 and 12%, a range that varies depending on the product category and total monthly revenue. As can be seen in Table 1, the commission also varies according to the product that is finally purchased. In other words, if the user buys the product from the direct link (direct link purchase) the commission is higher than if they end up buying any other product (indirect link purchase) (Amazon, 2021).

Table 1. Revenue rates for standard programme commissions for certain product categories on the Amazon.es website. Affiliate Programme Operating Agreement, effective 1 February 2021

Source: Amazon.es

More and more national digital media companies are including affiliate programmes in their content. Only to mention a few, ElPaís.com has had a permanent section called Escaparate (Showcase), which was created and has been used for this purpose since May of 2017; Elmundo.es created the Bazar section for “offers and gifts” in November of 2019 (previously it concentrated affiliate content in the Nole.com domain); Elconfidencial.com inaugurated its De compras (Shopping) section at the end of May 2019; and Elespañol.com introduced the space known as Los imprescindibles (The essentials) on its website for the same purpose in November of 2019.

1.3.5. Brand presence in Ad units and Widgets

Finally, there is also a tendency among digital media to include sections of advertising composed of ad units identified by the media themselves with words such as sponsored content or we recommend, although such content is not really sponsored content as defined above, but generally consists of Google advertising or “content recommendation platforms”, which is a term these companies use to define themselves, an example of which is Outbrain. Furthermore, the companies connect directly through external links to the brands that pay for these spaces. In these situations, some media choose to present this content under the umbrella term sponsored content, when the appropriate name to refer to them should really be advertising or, in any case, paid content, taking into account that the RAE dictionary (2014) defines the verb promote as “elevating or giving value to commercial items, qualities, and people”.

Along these same lines, there has also been a proliferation of content with a brand presence which, due to partnerships or agreements involving sponsorships, is embedded in widgets with links that connect externally and directly to the websites of the partners or sponsors.

2. Objectives and hypotheses of the study

2.1. Objectives

In the current context in which brands are exploring and increasing their budgets with new formats that connect with their audiences and transmit the brands’ values, the specific objective is to confirm how this trend is reflected in a generalist digital medium that is a leader in terms of audience. Furthermore, even more specifically, the aim is to verify how this content is identified both on the front page and within the texts, its typology, and authorship.

Thus, the specific objectives of this analysis focus on the following: to discover the amount of content with a brand presence that appears on the front page of Elpaís.com; analyse the location, section and format of each of them; identify the type of content with a brand presence to which each item belongs; determine how they are identified (or not) on the front page; and analyse the subject matter, brand visibility, authorship and type of link to the item from the front page.

This article specifically presents the results of an exploratory case study focused on the front page of ElPais.com, which is the first phase of a broader investigation aimed at analysing the presence of brand content in the Spanish digital press in which the objectives are addressed through a representative sample that is observed over a longer period of time.

2.2. Hypotheses

The hypotheses of this research that we intend to verify are as follows:

H1: The incidence of content with a brand presence in ElPais.com is high, due to the importance of such content for its business model, yet it is not always properly identified or differentiated from strictly journalistic content.

H2: The media sometimes make inappropriate use of the terms that define the different types of content with a brand presence when referring to them, which results in the content being presented to the reader in a confusing or inappropriate manner.

H3: A large part of the content with a brand presence is written by journalists and collaborators working for the medium.

3. Methodology

In order to address the objectives set forth, a quantitative content analysis was carried out between May and June of 2019 of the content with a brand presence that appeared on the front page of the digital newspaper Elpais.com.

Regarding the case under study, Elpais.com was chosen as the sampling unit due to the fact that it was the leading generalist digital media in Spain during the period when the design of this research was carried out. Between the months of March and April of 2019, ElPaís.com was the medium with the most traffic, according to the Comscore index (the official provider of measurements of digital media audiences during the research period), with 20.3 million unique users in March, and 21.7 million in April. During the data recording and quantification phase, the number of unique users for ElPaís.com was 23.2 million in May (surpassed by La Vanguardia at 23.4 million), and 21.3 million in June, when it regained the lead.

In order to count the number of items with a brand presence, an analysis was carried out of the content that appeared on the front page of ElPaís.com. This context unit was chosen because the front page contains “sound assessments of current affairs that media managers use to attract the audience. It contains headlines and other content... that act as showcases where the intention is to reflect all of the content of the newspaper” (Andréu, 2002: 13-14).

3.1. Unit of analysis

Based on research carried out by Krippendorff (1990), the unit of analysis in this research is understood as “the part of the sampling unit that can be analysed in isolation” (Andréu, 2002: 13), which in this case corresponds to the items with a brand presence. The items analysed in this study are those previously presented in the introduction and state of the art section: branded content, native advertising, sponsored content, and affiliate content, as well as advertising items resulting from sponsorships or partnership agreements included in widgets, or identified by the medium itself as sponsored content located in ad units. Traditional display advertising in the form of banners and other standard advertising formats have been excluded from this study.

In order to select the unit of analysis, a detailed reading of all the items on the front page was carried out, including those in which the following parameters were present:

- Items identified as brand content according to a logo, an explanatory tagline, or text identifying the item as advertising, publicity, or sponsored content.

- Items from sections that are sponsored, or that result from agreements with brands, such as the section called Training (Emagister) or the one entitled, My finances (iAhorro)

- Items that mention a brand in the headline and, once inside, they are identified as brand items.

- Affiliate content items from the Escaparate section or the subdomain entitled Librotea (Books).

3.2. Analysis period

After a two-month period of observation (March and April of 2019), and a 15-day testing period (15 April to 30 April 2019), the first phase of the fieldwork took place between 1 May and 30 June of 2019. A two-month period was selected in order to recognise and distinguish brands that reserve spaces for several months from those that do so for shorter periods of time, and to have a record of both.

3.3. Procedure

The appearance of advertising content was measured three times per week, two times during the week from Monday through Friday (due to the fact that during the testing period a greater volume of advertising content was observed on these days), and one time at the weekend (Saturday or Sunday), in order to study whether differences exist between weekdays and weekends, and the nature of such differences. To obtain the content items analysed, the information was extracted on alternate days as follows: Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday for one week; and Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday the following week. This continued until the entire nine weeks of the study were completed.

The analysis was always carried out in the evening between 18:00 and 00:00 hours, as it was observed during the testing period that the front page of the newspaper is generally more stable and undergoes fewer changes in the evening, and always before 00:00 hours, because at that time the content featuring brands sometimes changes when the 24-hour period of publication finishes. The entire analysis was carried out using the same 15-inch laptop computer in order to visualise the location of the items on the front page in the same way each time.

At the end of the study, data had been collected from 28 front pages on all days of the week (4 pages from each day) in order to have a record of all active campaigns regardless of the day for which their publication had been reserved. A total of 3,330 content items on front pages were reviewed, and 545 items that were identified as content with a brand presence were analysed. In addition, screenshots of the front pages were taken and archived, as well as the links of all items analysed during the entire research period.

In order to carry out the content analysis, tables were created in Numbers for Mac, and the online tool Wayback Machine was used to review and debug the data.

3.4. Variables

- Day of the week (Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday)

- Vertical location (front page hierarchy based on scrolls from 1 to 10)

- Horizontal space occupied (1/4, 1/3, 1/2, 2/3, 1/1).

- Image size (small, medium, large).

- Position (left, centre, right).

- Type of identification on the front page:

- Not identified as brand content on the front page, but within the item.

- Identified with a text label (A project by... Created by...).

- Identified using the brand’s logo.

- Identified using the words sponsored content.

- Identified using text or labels containing the word advertising.

- Type of link to the item from the front page (internal link to a section of the medium, internal link to a subdomain of the medium, internal link to a specific advertising section, external link to the brand).

- Brand presence on the front page (whether or not the brand name is displayed on the front page, and how it is displayed).

- Section in which the item was published (culture, sports, economy, education, showcase, Spain, lifestyle, promotions and advertising, health, society, subdomain or supplement, technology and science, and television).

- Item topic (culture, sports, economy, education, gastronomy, home and family, environment, automotive, solidarity, health and nutrition, technology and science, television, travel, and others).

- Type of content with a brand presence (this variable takes into account the categories mentioned above: branded content, native advertising, sponsored content, affiliate content, and advertising items included in widgets and ad units identified by the medium itself as sponsored content).

- Item format (video, text, image, interactive content).

- Brand presence in the item (whether or not the brand name is displayed within the item, and how it is displayed).

- Authorship of the item: writer, media, media collaborator, branded content department, brand, and brand collaborator.

Once inside the item, in order to identify the type of branded content to which each item belonged, the definitions established in the literature review presented in the introduction and state of the art section of this study were used.

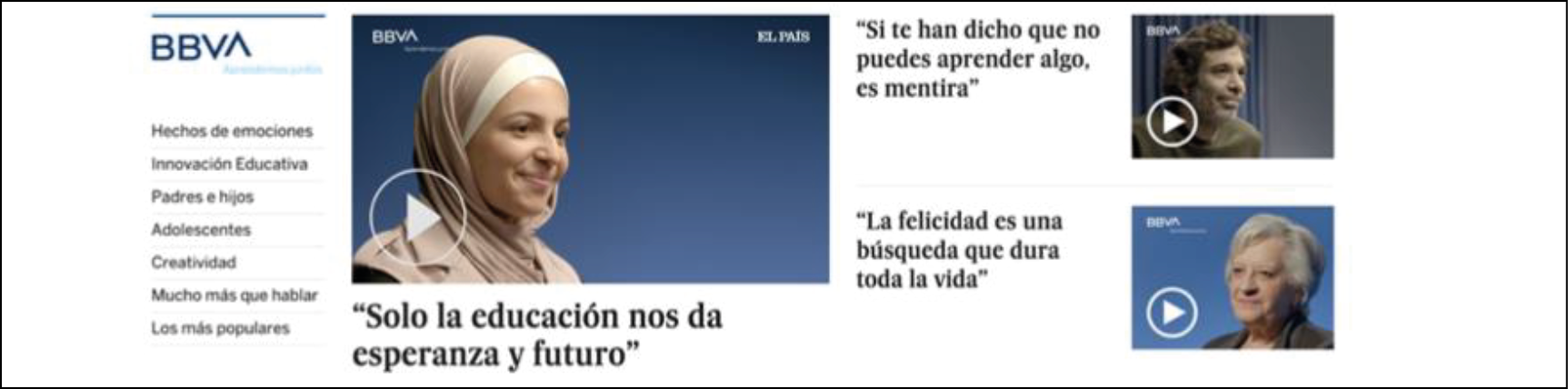

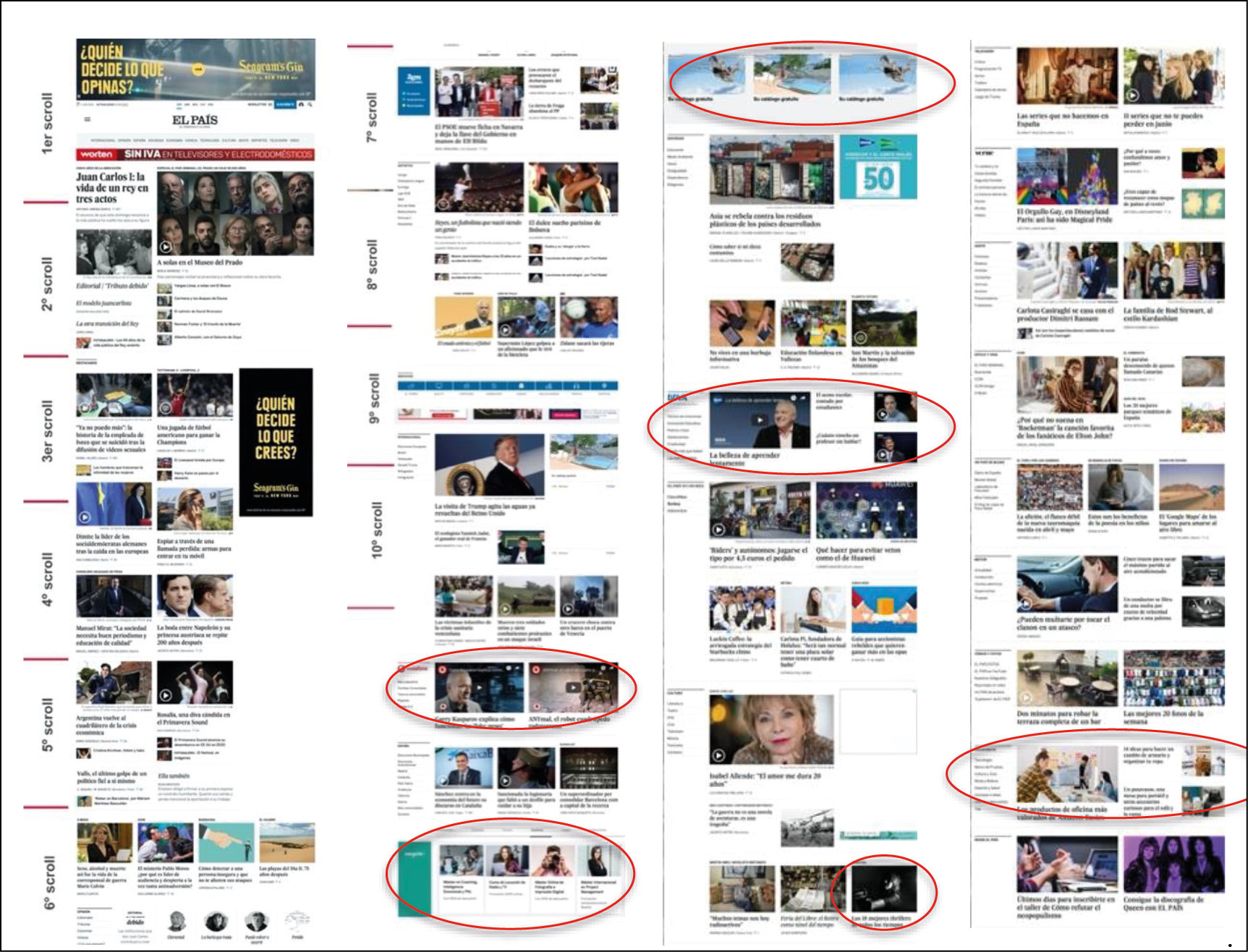

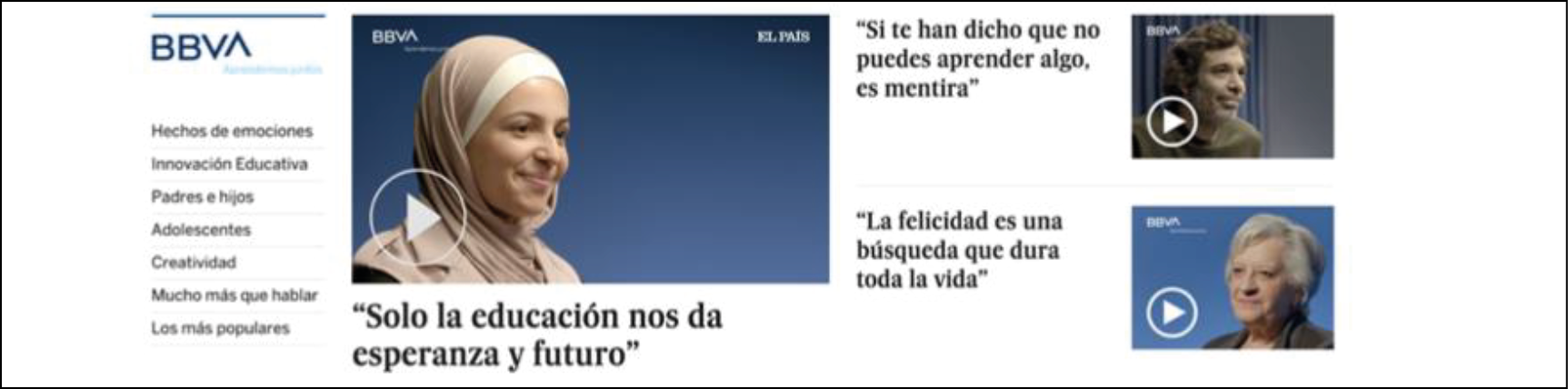

In order to distinguish branded content (Image 1) from native advertising (Image 2), we have taken into account the definitions provided in the theoretical section and the parameters that were mentioned as well, such as whether they explicitly include the product or service, or whether they are more focused on the values of the brand.

Image 1. Example of branded content. Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 6 June 2019 at 19:17h.

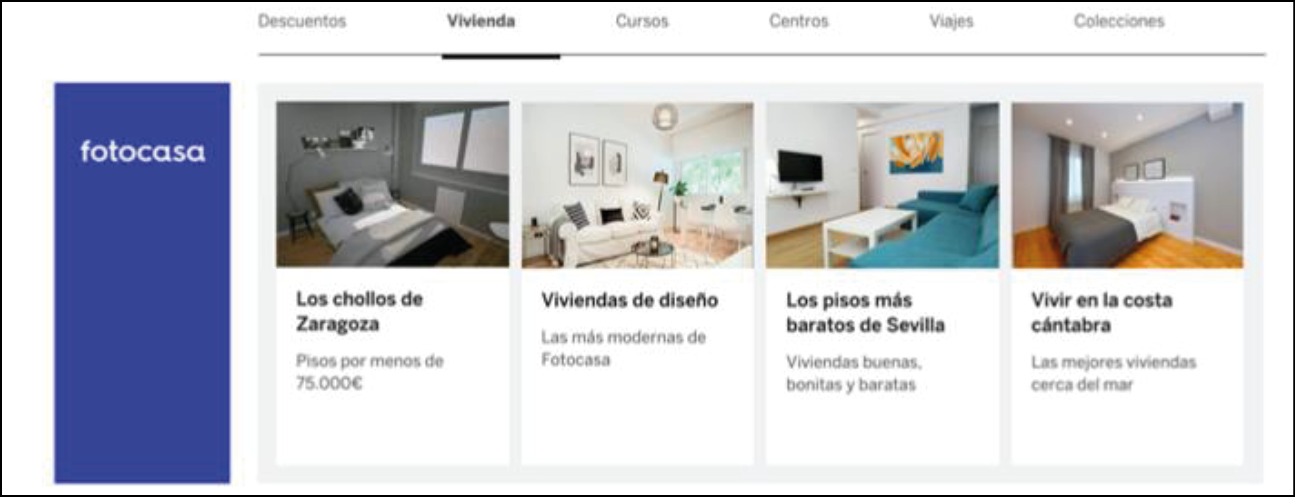

Image 2. Example of native advertising. Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 14 May 2019 at 23:39h.

On the other hand, sponsored content (Image 3) has been counted as content that forms part of a section sponsored by a brand, or is the result of a partnership agreement with a brand, according to the definition provided in the introduction.

Image 3. Sponsored content with a brand presence. Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 21 May at 20:38h.

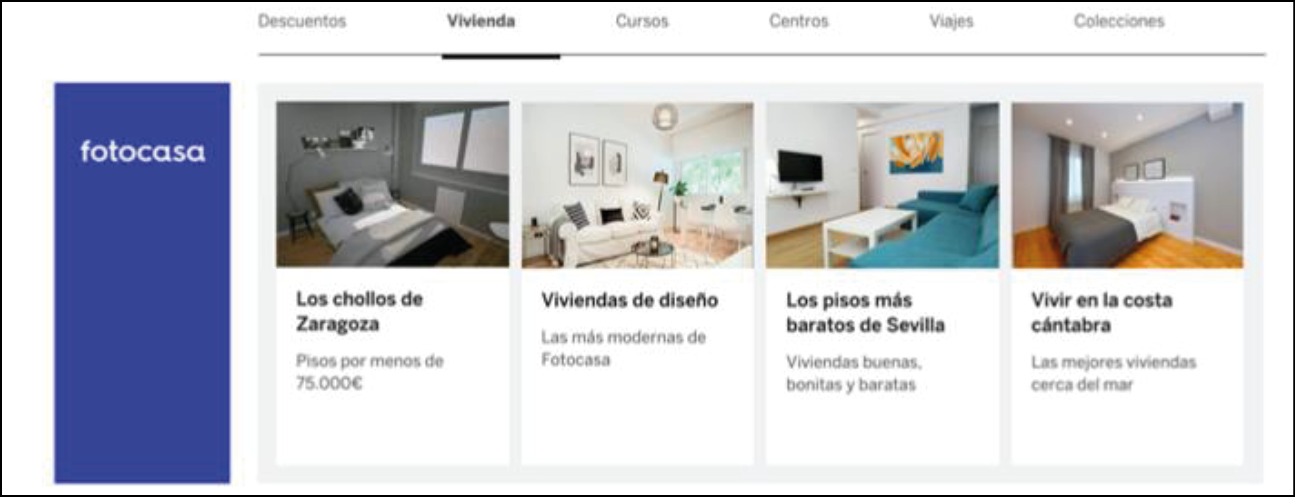

With regard to affiliate content (Image 4), we have analysed the front page of the Escaparate section (where products from different categories are shown) and of Librotea, a subdomain of the media focused on the recommendation and sale of books.

Image 4. Affiliate content items. Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 18 June 2019 at 19:00h.

Finally, we have also included the items that appeared in sections on the front page of ad units (Image 5), identified by the media itself as sponsored content, as well as content with a brand presence resulting from sponsorships or partnership agreements integrated into widgets (Image 6), the links of which connect externally and directly to their web pages.

Image 5. Ad units under the heading of ‘Sponsored Content’. Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 8 May 2019 at 22:11h.

Image 6. Widget with a brand presence of Emagister. Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 25 May 2019 at 21:37h.

3.5. Coding and reliability

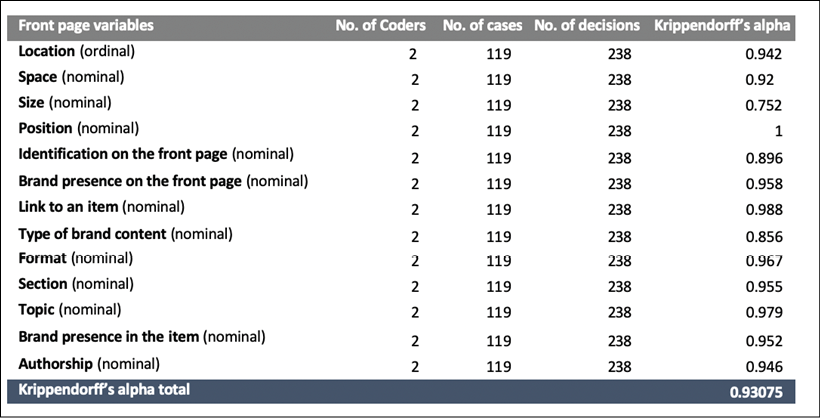

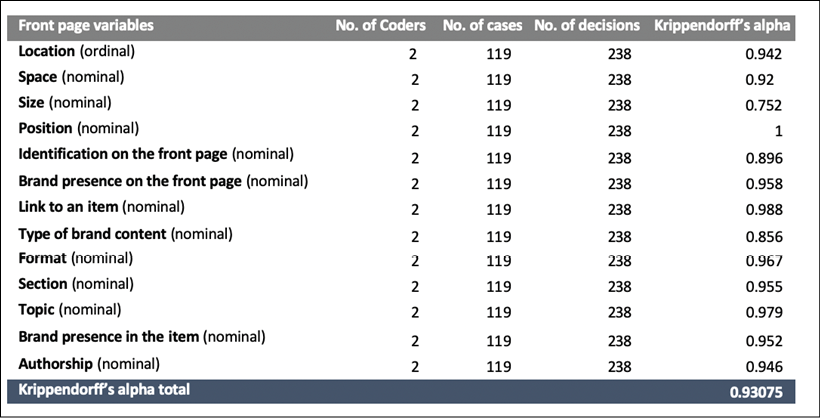

During the observation and testing period, two researchers participated in the fieldwork to establish all the variables necessary to measure the volume and characteristics of content with a brand presence on the front page and within the content item as well. After defining the 14 variables, the observers simultaneously analysed 13 of them during the testing period (the day of the week variable was excluded because both researchers carried out the study on the same day), out of a total of 119 items, which is 21.8% of the total number of items in the final sample of the study, obtaining a Krippendorff alpha coefficient of 0.93% out of 1 (Table 2). This means that the agreement between both coders is above the admissible lower limit (0.667), and the minimum acceptable limit, which stands at 0.8 (Krippendorff, 2004: 242). To calculate the Krippendorff alpha coefficient for each of the variables, the ReCal tool was used for ordinal variables (vertical location) and nominal variables (the rest of the variables), resulting in a high level of reliability and inter-observer agreement.

Table 2: The Krippendorff alpha coefficient of agreement between the two coders of the study for each of the variables, and the total calculated using the ReCal tool

Source: prepared by the author

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of brand content on front pages

On the 28 front pages of ElPaís.com analysed during this study, the figure of 545 items with a brand presence were identified out of a total of 3,330 items counted, which represents 16.3%. This means that if the average daily number of items on the front page of this medium is 119, the average number of items with a brand presence is between 19 and 20 per day. It should be kept in mind that display advertising formats have not been taken into account in this analysis.

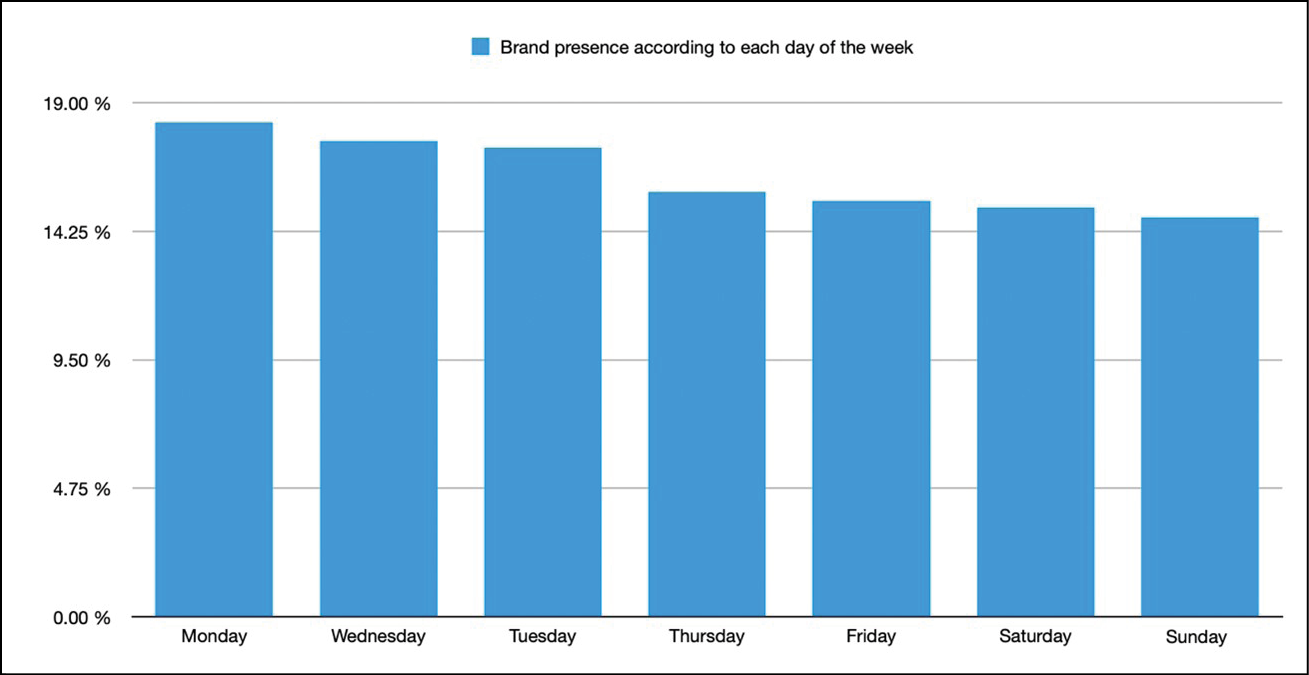

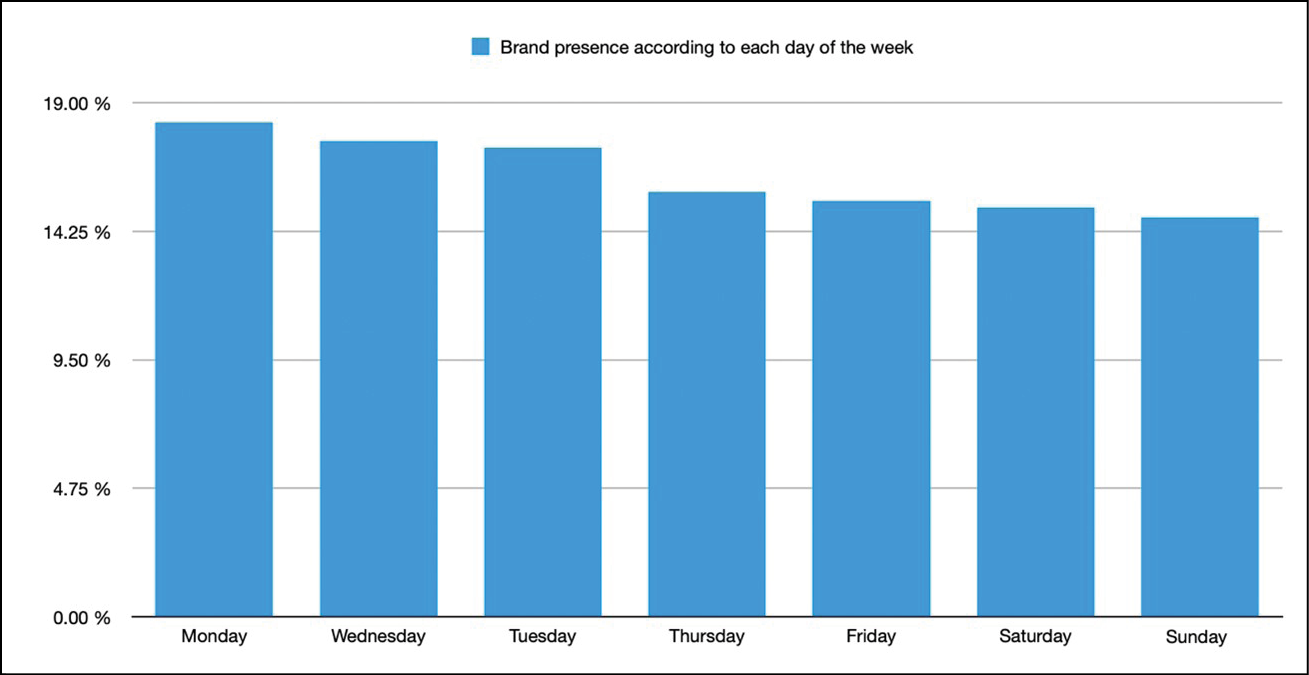

Based on the overall averages according to each day of the week (Graph 1), no major differences have been observed, although the percentage is higher on weekdays than at the weekend. The day of the week with the highest average number of items with a brand presence is Monday, at 18.28%, and the lowest is Sunday, at 14.76%. During the study phase, the days with the highest number of items were Tuesday and Wednesday (24 items), and the day with the lowest number was Sunday (14 items). This trend might be associated with two fundamental factors: firstly, the higher amount of web traffic registered by the newspaper on weekdays compared to weekends (Solís, 2016: 212); secondly, the topics and genres published, which on Saturdays and Sundays differ from those published on weekdays (Benaissa, 2018: 62). However, this situation does not seem to be related to a reduction in weekend prices compared to other days of the week, as this factor is not mentioned in the El País 2019 price rate document published on its website (Prisa Brand Solutions, 2019).

Graph 1. Average brand presence on the front page by day of the week ordered from highest to lowest presence

Source: prepared by the author

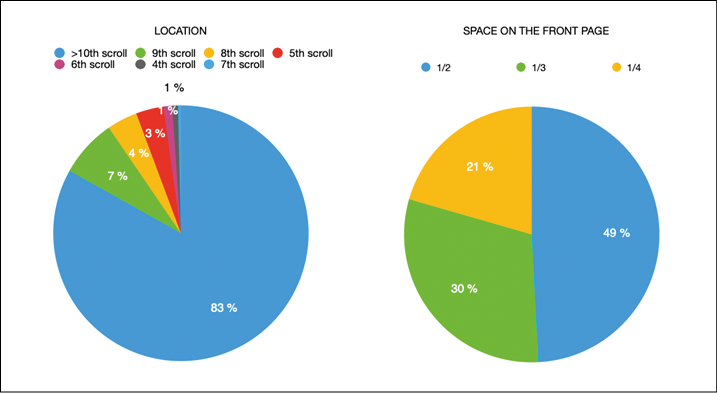

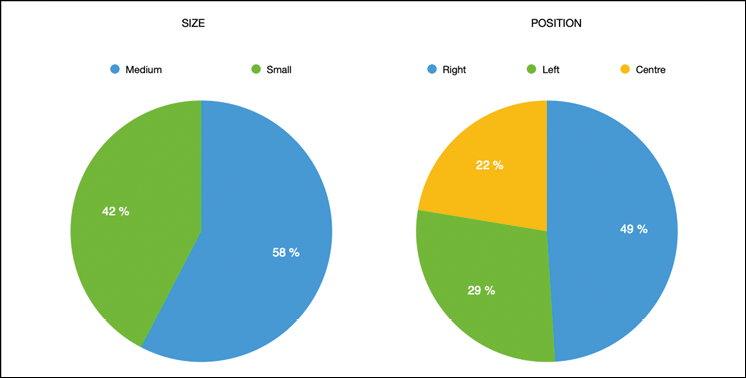

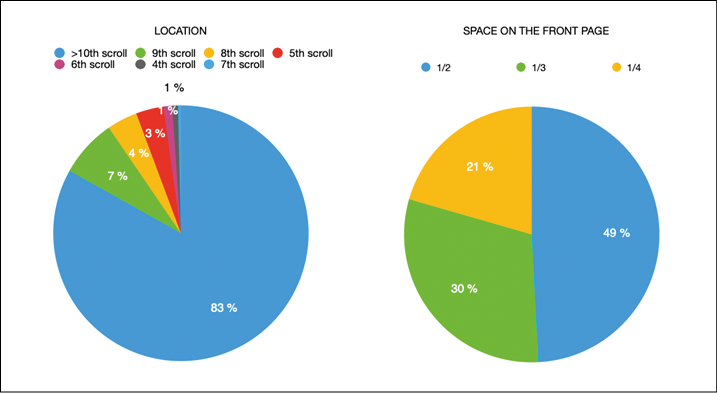

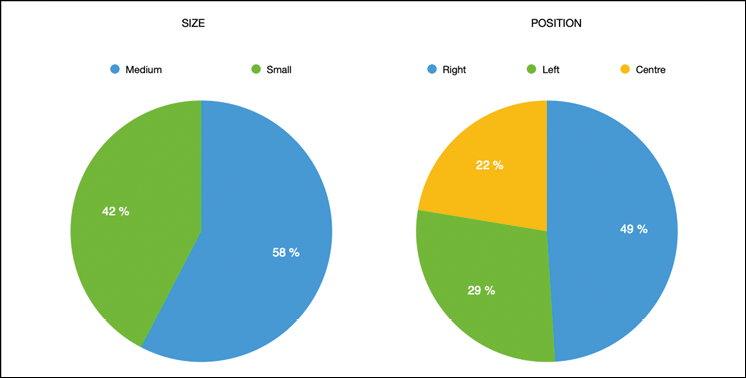

With regard to the location they occupy on the front page, different variables have been measured, such as vertical positioning or front page hierarchy (Graph 2), which measures the position with regard to the number of scrolls or, in this case, downward mouse movements that must be carried out to see the item; the space size it occupies (Graph 3) – 1/1, 1/2, 1/3 or 1/4 of the row in which it is located; the size of the image (Graph 4)– large, more than 251 pixels high– medium, between 151 and 250 pixels– or small, less than 150 pixels; and finally, the horizontal position of the item (Graph 5)– left, centre or right.

Location occupied on the front page by content with a brand presence.

Graph 2. Location (vertical hierarchy). Graph 3: Space (horizontal hierarchy)

Source: prepared by the author

Location occupied on the front page by content with a brand presence.

Graph 4. Image size. Graph 5: Position

Source: prepared by the author

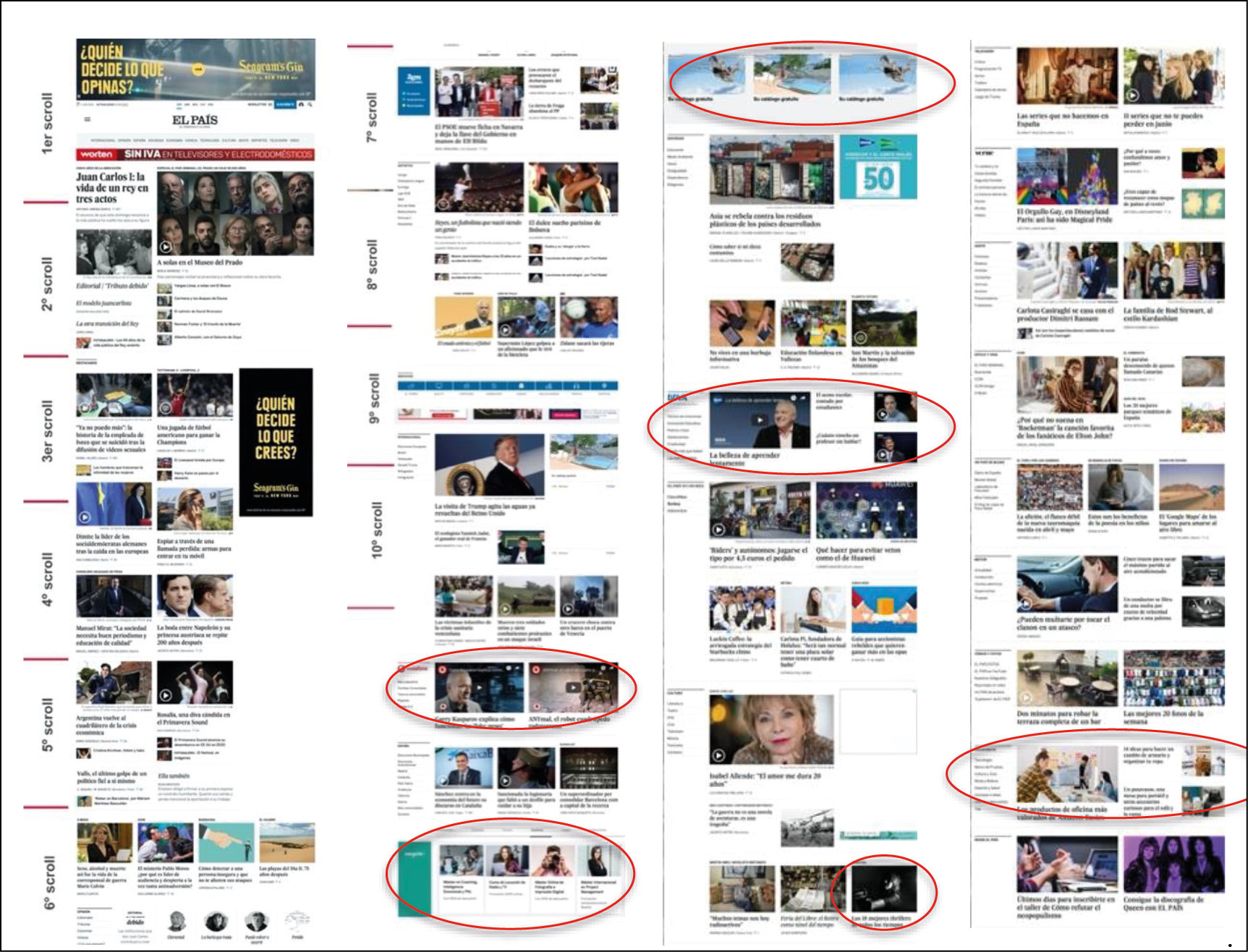

In terms of vertical hierarchy or positioning (Graph 1), the scroll has been chosen as the unit of measure due to its status as the system currently being used by premium audience measurement tools in media such as Chartbeat, and it is used by Elpais.com itself for this purpose as well. Similarly, theorists such as Nielsen (2015) and Fessenden (2018) have also used the scroll as a unit of measure in their studies. In this regard, the observation has been made that 83% of the items (452) have been found from the tenth scroll onward, or in other words, quite far down. Only from the fourth scroll onward does the first brand content appear on the front page, and only four items in total were found in that position, which represents 1%. In the fifth scroll, a total of 19 items were found (3%), while in the sixth and seventh scrolls a total of 8 items were counted (2%). As we scroll down further, more items appear, totalling 21 in the eighth scroll (4%) and 40 in the ninth (7%).

In short, content with a brand presence is generally concentrated at the bottom of the page. Again, this trend could be associated with a reduction in the rate according to the vertical hierarchy of the newspaper. However, no reference to this aspect has been found in the El País 2019 price rate document (Prisa Brand Solutions, 2019). According to the latest Nielsen Eye Tracking study published in 2018, users spend 57% of their time viewing the top half of the first page, 17% on the second scroll, 7% on the third scroll, 5% on the fourth, and 3% on the fifth. Thereafter 2% on the sixth, 1% on the eighth and ninth, and 5% from the tenth onward. However, compared to the study carried out in 2010 by the same consultancy firm that specialises in UX (user experience), the 2018 report revealed that in the previous eight years, users had become more accustomed to scrolling, since the first study revealed that the percentage of time spent on the first screen without scrolling (the space called ‘the fold’) was 80% (Fessenden T., 2018).

Image 7. Front page of Elpais.com on 2 June 2019 that shows the scroll measurement of a 15-inch laptop in relation to content with a brand presence circled in red from the 10th scroll onward

Source: prepared by the author

If we look at the space occupied by the items under study in the row in which they are placed, according to the horizontal hierarchy (Graphs 2, 3 and 4, and Images 8, 9 and 10), it can be seen that nearly half (49%) occupy half of the row, while 30% occupy 1/3, and the remaining 21% of the items occupy 1/4. The size of the images is medium-sized (58% of the items studied measure more than 151px), and small (42% measure less than 150px). Finally, nearly half of the items analysed are positioned on the right-hand side of the page, while 29% are on the left, and 22% are in the centre.

Image 8. Branded content of 1/2 size. On the left, a medium-sized image (between 151 and 250px) and on the right, a small one (less than 150px high). Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 23 June 2019 at 21:52h.

Image 9. On the right, 1/3 sponsored content with medium-sized image (between 151 and 250px high). Screenshot of the front page of ElPaís.com on 20 June 2019 at 18:30h.

External link widget of 1/4 size with small images (less than 150 pixels). Screenshot of the front page of

ElPaís.com on 13 June 2019 at 22:24h.

The following variables of the front pages studied measure how these items are identified: whether they are identified as items for which a brand has paid, produced, or sponsored; whether or not the brand’s name or logo is displayed on the front page, and how it is exhibited; and finally, the place to where the links lead (to the same media outlet, to a subdomain of the media outlet, or to external websites).

The figure of 21% of these items are not identified as paid or brand-sponsored content, while 79% are identified in diverse ways. Those not identified correspond to affiliate or sponsored content (section sponsorship). Of those that are identified, 52% do so by showing the brand logo, and 21% identify the items in the form of ad units identified by the medium itself as sponsored content, but which, as mentioned above, contain Google display advertising and are not sponsored content as this typology has been defined in this study. Only 3% identify the items with a tagline that contains the word advertisement in some form, and the remaining 3% also identify the items using text but without using the word advertisement. Native advertising, branded content and content included in widgets and ad units are duly identified in some way as brand content.

Regarding the way in which the brand is displayed on the front page, 53% show the brand name with the logo, 9% use text, 1% use the logo and text, and 37% do not show the brand name in any way whatsoever. It is important to clarify that most of the content that does not display the brand name is affiliate content or advertisements presented in ad units displayed under the misleading label of sponsored content.

To conclude this section, the type of link in each item has also been analysed. A total of 40% are linked to the different sections of the medium itself under the domain of Elpais.com. The figure of 33% are external links that open in another tab and connect to the brand’s website, all of which belong to content included in widgets or ad units. The remaining 27% are linked to a subdomain of the media itself, either supplements such as Smoda, vertical portals such as ElComidista or Librotea, or branded content landing pages such as BBVA’s Aprendemos juntos (We learn together), or Vodafone’s El futuro es apasionante (The future is exciting).

4.2. Characteristics of the items with brand content

Once the items were accessed from the front page, external links were excluded and only those that link from the front page to the same medium or to a subdomain of the same medium have been taken into account. Among this group, the first element identified is the section where the content is located. A very high percentage of this variable (40%) connect through a link to a branded content subdomain within the medium, 22% to the Escaparate (Showcase) section where affiliate content is grouped, 14% to the Economía (Economy), 12% to one of its supplements, or vertical portals, 3% to the Deportes (Sports) section, 3% to the Sociedad (Society) section, 2% to a specific Promocion o Publicidad (Promotion or Advertising) section, and the remaining 2% to Motor (Automotive), Viajes (Travel), and Álbum de fotos (Photo Album).

With regard to the topics addressed by these items, the first thing that has been observed is that they are not always identified with the brand’s activity, but rather with the values used by the brand to identify itself.

This is the case of BBVA, for example, with the campaign Aprendemos juntos (Let’s learn together), which focuses on Education, or the campaign entitled Pienso, luego actúo (I think, then I act) by Yoigo, which focuses on content that is “changing the world for the better” through entrepreneurship and activism from a social perspective. The campaign carried out by BBVA in ElPaís.com was large-scale in terms of its duration and the number of items included (three content items on the same front page and as many as four on some days), which means that the balance is considerably tipped in favour of the Education topic at 27%. To a lesser extent, the same situation occurs with Vodafone’s branded content campaign related to Technology (presented on the front page with content consisting of two videos), which boosted the average figure for this topic to 20%. The prolonged time span of these campaigns reveals another characteristic of branded content, as this type of content requires months and even years to achieve its final objective: to establish emotional links with its audience and increase its renown. Moreover, as these campaigns demand a high level of investment, they require more time to obtain a return on investment as well.

With regard to affiliate content (three per day are shown simultaneously on the front page), it is often found in the Technology section, although it appears to a greater extent in Hogar y familia (Home and Family), the latter of which is a subject that reaches a total of 13%, and in Moda y belleza (Fashion and Beauty), the figure of which stands at 7%.

At 11%, Economy is another of the topics most frequently covered by the items with a brand presence, and its content is focused on aid to SMEs, investment, and advice for household economy; Telefónica, iAhorro and Correos are some of the brands with the greatest presence in this area.

The vertical portal Librotea follows the same pattern with Culture (7%) by using content that contains affiliate links to online bookshops, and the branded content activity of La Liga raises the Sports topic to 4%. Gastronomy, Health and Nutrition, Environment, Automotive, Travel and Solidarity complete the list with percentages between 1% and 2%.

At the same time, we also analysed the subject matter of the items with a brand presence included in the aforementioned widgets or ad units that link directly to their websites. The latter, as they come from Google, tend to show repeated advertisements, yet they are personalised according to the navigation or preferences of each person, so the subject matter registered here is not entirely reliable, despite the fact that in order to avoid this bias, this part of the study was carried out using incognito sessions.

In any case, it is striking that 46% of these external links are focused on Education, mainly as a result of the collaboration agreement between Emagister and the Domestika advertisements; 26% on Home and Family, mainly due to the Abrisud ads; 17% on Economy, partly due to the collaboration agreements with iAhorro and Fotocasa; and 4% on Automotive, through ads from brands such as Renault, Seat, and Volkswagen.

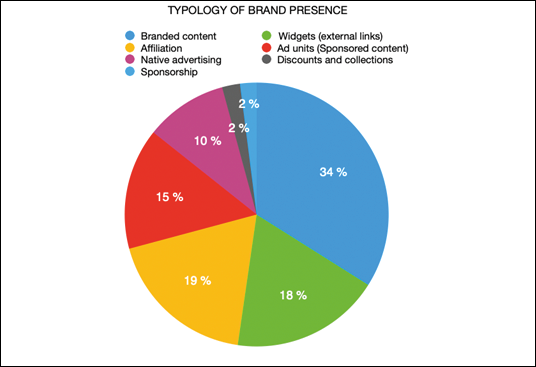

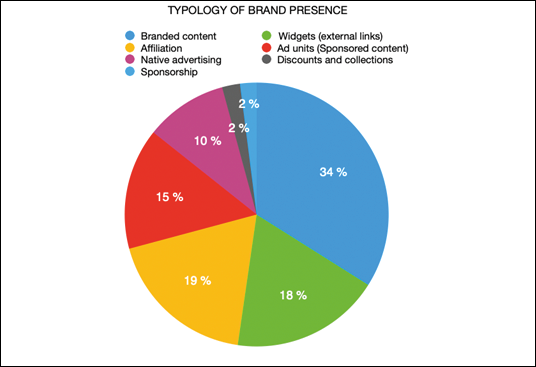

The following section refers to one of the most important aspects of this study: the typology of content with a brand presence and the formats of these items (Graph 6).

Graph 6. Typology of brand presence in ElPaís.com

Source: prepared by the author

During the period analysed, significant branded content campaigns were carried out in Elpaís.com. These includes the aforementioned campaigns by BBVA, Vodafone, Yoigo and Telefónica, the first two of which have their own subdomain with a direct link to a unified landing page with content. In addition to these campaigns, others such as those of La Liga, Carrefour, and Orange, all of which were prolonged over time throughout the period of analysis and therefore had a concentration of numerous content items, brought the number of branded content items linked from the front page to a total of 34%.

With a total of 19%, the next most prevalent category is affiliate content, which includes two types of articles. The first are lists of product selections or comparisons with purchase links to online shops based on agreements between the media outlet and the shop itself (Amazon, Ebay, Pccomponents, Cecotec, El Corte Inglés), or with affiliate networks (Awin). Depending on the contract with each of them, the media outlet receives a commission that can vary on average between 3% and 5%, depending on the products that the user eventually buys, and whether or not the user buys the product to which the media outlet makes a direct link, or instead buys another product not included on the list. Of this content, three per day are shown on the front page and new articles are published each day. The second type of affiliate content found was published in the reading content subdomain of Librotea. In each of these items, we found a shelf with a list of books that at the time of the study could be purchased in different online bookshops (Amazon, Casa del Libro or Fnac). At the time of this writing, Librotea’s agreement is only with the online bookshop Casa del Libro.

Advertising content items inserted into widgets also have a presence of 18%. At the time of this study, the widget had five tabs (Discounts, Housing, Courses, Centres, Travel, and Collections), to which a Mortgage tab was later added, although during the analysis, screenshots were taken only of the external content of Emagister courses, of the Homes tab on three occasions with external content from Fotocasa, and of Mortgages on one occasion with external content from iAhorro. The Courses tab is the result of a collaboration agreement between El País and Emagister which, in addition to displaying courses in the widget that link directly to its website, includes the sponsorship of a Training section with content produced by the medium itself. However, these latter items have been counted as part of the sponsored content section.

Likewise, the content of the widget included in the Discounts (which have appeared on two occasions) and the Collections tab (which present Collectables from El País) have not been counted in this section, but rather in the Discounts and Collections section, which account for 2% of the total, due to the fact that the content of both are not external links to other pages, but are produced in-house and are hosted under the domain of Elpais.com. This content has been considered separately as they do not fit exactly into any of the typologies observed in this study.

With regard to items integrated into ad units, their presence accounts for 15% of the total. As in the case of widgets, these items link to external pages of the brands being advertised.

It is worth recalling that the only reason why these items (which could be considered display advertising) have been taken into account is due to the fact that the format is identified by the media itself as sponsored content, although as previously mentioned, this content does not fit the definition of sponsored content provided in this article.

Accounting for 10% of the total number of items on the front page, native advertising is the next most prevalent category with a total of 55 items registered from 43 different brands that focus on providing visibility to the brand’s activity. Economy (18), Home and Family (7), Technology (7), Automotive (6), Fashion and Beauty (4), Travel (4), Health and Nutrition (3), Environment (2), Education (2), and Sports (2) are the most recurrent topics. In this section, we find brands such as Mitsubishi, Ikea, Correos, Aquarius, Desigual, Seat, and KMPG, among others.

Items registered as sponsored content or sponsorships is limited to 2%, due to the fact that as we have seen, only content that has resulted from a sponsorship agreement of a permanent section of the newspaper by the brand has been taken into account in this category. In some of this content, there is a brand presence in the text itself, but it is limited exclusively to the display of its logo.

In 2014, El País entered into a partnership with iAhorro (8 items) with the aim of “improving the personal finances of its readers”, by inaugurating a new section within the Economy category under the title of ‘My savings’, currently called ‘My finances’, which includes content focused on investment planning, savings plans, and household economy. For its part, Emagister (2 items) also began to collaborate with ElPaís.com in 2014 and, in addition to having a widget presence in its courses, it also sponsors the Training section in which it publishes content related to Education, penned by writers from the medium itself. Finally, Wolters Kluger (1 item), signed a partnership agreement with PRISA Noticias in 2017 to include a section with legal information within the Economy section of El País. Under the title of ‘My rights’, several content items are published each month, of which only one has been found on the front page during the research period.

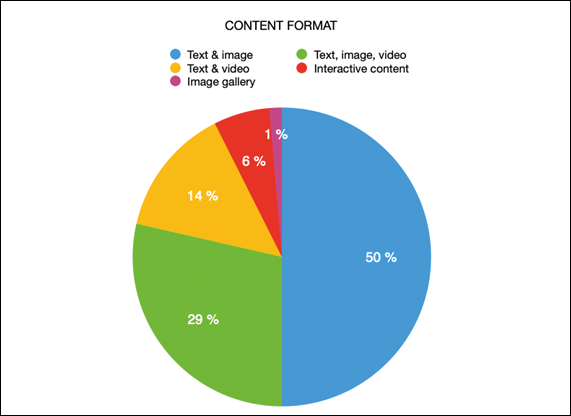

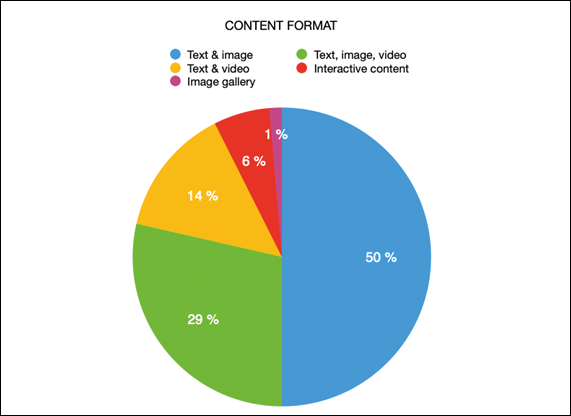

By focusing attention on the content format (Graph 7), it can be seen that 50% of the items are presented in the traditional style of text and image. Approximately 29% combine text and image with video, while 14% use a combination of text and video. Content that requires user interactivity accounts for 6% of the total number of items, with one of the most attractive examples being Telefónica’s Think Big branded content project. Finally, the figure of 1% used image galleries or photo albums.

Graph 7. Content format in ElPaís.com

Source: prepared by the author

Analysing the format regarding typology, it can be seen that affiliate content, native advertising, and items included in sponsored sections are the most inclined to show information in a format using flat text and image. Branded content, however, uses more attractive multimedia formats, including video, image galleries, graphics, and other interactive elements.

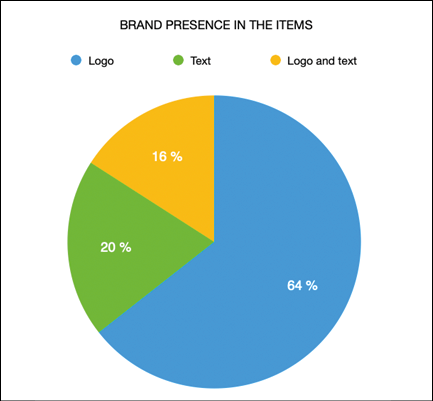

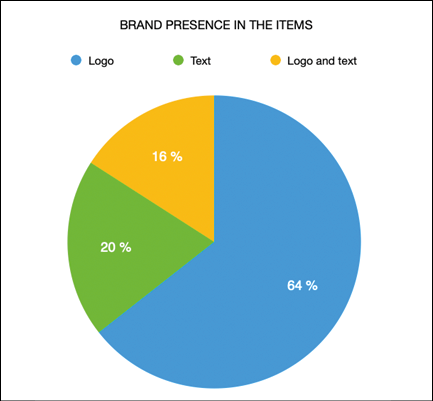

In order to study the variable of brand presence within the item (Graph 8), affiliate content has not been taken into account, due to the fact that even though there is a presence of the various brands of the products that have been selected in all of the items, these brands in theory do not pay the media for being included in this type of article, but instead they pay Amazon, Awin or the online shop responsible for selling their products. In any event, the brand of each of the products linked to the corresponding online shop is mentioned in all of the items. The items contained in widgets or ad units, which from the front page linked externally to other websites, have not been considered either, since the study focuses on the items published in Elpaís.com or its subdomains. Thus, taking into account the other three categories under study (branded content, native advertising, and sponsored content), it can be concluded that 64% of the brands choose to show the logo in the content without mentioning the brand in the text, while in 20% of the items analysed the brand name can be read in the text, and in 16% of the items it can be observed that both options are combined, which include showing the logo and mentioning the brand in the text as well.

Graph 8. Brand presence in the items in ElPaís.com

Source: prepared by the author

If we cross-check this data with the typology of brand presence, we can observe that the contents that show only the logo are more related to sponsorships and branded content, while the native advertising content usually shows the brand in a way that is integrated into the text.

It also bears mentioning that once inside the items, they are duly identified as brand content, although this is not always done in the same way and can sometimes be confusing (Image 11).

Image 11. Ways of identifying brand content in ElPaís.com and some of its subdomains

Source: prepared by the author

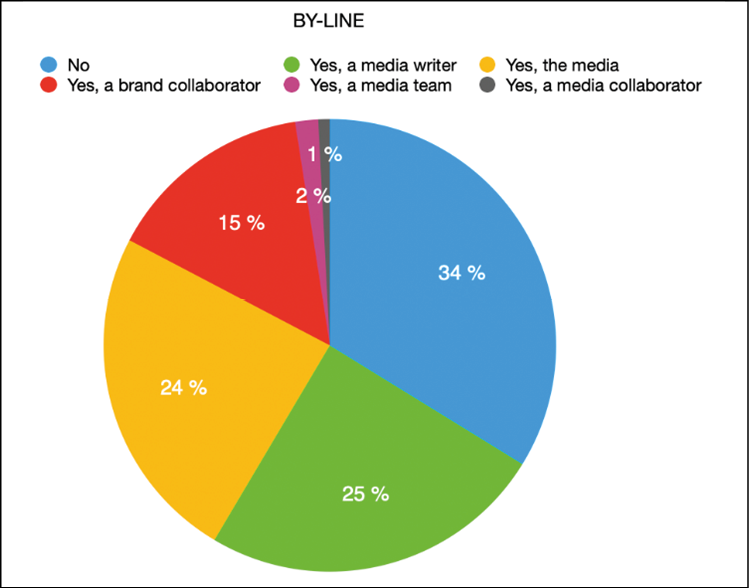

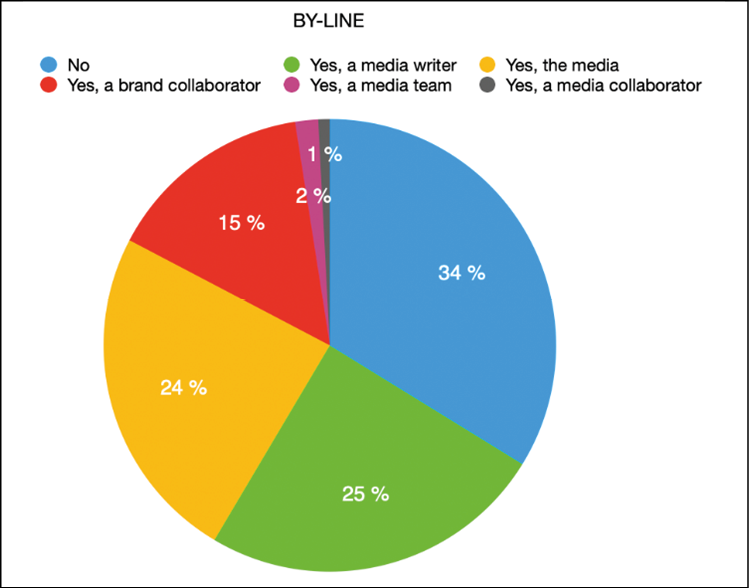

At this point, an analysis has been carried out to determine who is responsible for the production of these items based on the by-line of the articles (Graph 9). The purpose was to find out whether or not this task is being performed by the journalists of the medium.

Graph 9. Source of the items with a content presence in ElPaís.com according to the by-line

Source: prepared by the author

Based on the results obtained, it can be affirmed that 34% of the pieces are not signed, although the bulk of this percentage is attributed to BBVA’s branded content. A total of 28% of the items are signed by writers, of which 25% are signed by media writers, 2% by a media team composed of several people, and 1% by media collaborators. In these items, we have found native advertising, comparisons in affiliate articles, and some branded content. A total of 24% are signed by the media outlet or the corresponding section of the media outlet, and here again we find items from all categories, including affiliation, branded content, and native advertising. A total of 15% are signed by a collaborator of the brand hired to produce this type of content, and this is specifically the case with the branded content campaigns of Vodafone and Yoigo.

If we make a sum total of the items with by-lines of writers, teams, collaborators of the medium, or the medium itself (whose authorship also corresponds to writers), we find that more than half (51%) of the content with a brand presence published in Elpais.com is written either by journalists from the newsroom, by La Factoría advertising content company, or by media collaborators. It is possible that the remaining 49%, which is not signed or is authored by brand collaborators, is also written by journalists who work in advertising agencies or content marketing departments of the brands themselves, although the information necessary to confirm this supposition is lacking.

5. Conclusions

Based on the present study and data extracted from ElPaís.com, it can be seen that content with a brand presence accounts for 16.3% of the content shown on the front page of this medium, which represents a daily average of 19 pieces out of the 119 published. Thus, there is no doubt that brands have a growing interest in both digital content and digital media, as pointed out by various experts and studies related to digital marketing (Carcelén, Alameda and Pintado, 2017; Miotto and Payne, 2019). This percentage is considered high a priori, as noted in the first hypothesis of this article, although the conclusion needs to be supported by a broader comparative study, one of which is currently being carried out with an evaluation of the front pages of other Spanish generalist digital media over a longer period of time.

If we look at their visibility, even though no significant differences have been detected among the various days of the week, Monday is the day with the highest volume of items (18.28%), and Sunday is the day with the lowest (14.76%). This aspect is closely linked to the fact that web traffic in the newspaper is slightly higher on weekdays, and is also related to the type of content published and consumed according to this variable. However, this aspect does not seem to be associated with a reduction in rates, as this issue is not included in the list of El País price rates (Prisa Brand Solutions, 2019). Nor is there any reference in this list to the vertical hierarchy of the content. Consequently, considering that the 2018 Norman Nielsen eye tracking study found that users spend 57% of their time viewing the top half of the page, and that this percentage decreases as they scroll down the page, the low level of vertical visibility of the items with a brand presence in Elpaís.com is striking, as 83% are concentrated at the bottom of the front page from the tenth scroll onward.

With regard to their presence on the front page, even though 79% are identified in some way as brand items, they do not always use the appropriate term, which may cause confusion for the reader. Firstly, it has been observed that 58% of the items are identified in some way as brand content by means of a logo or a text tag with ‘A project by... ’, or ‘Created by...’, although it has been found that the word advertisement is avoided when referring to them, and in fact this word was only used in 3% of the cases counted. On the one hand, this aspect is closely linked to the stagnation that has occurred in traditional advertising, and on the other hand is connected to the trend to explore new, less intrusive advertising formats (Cerezo, 2017; Miotto and Payne, 2019). Another noteworthy aspect is that 21% of the items presented under the heading of sponsored content are ad units serving Google ads. However, sponsored content is a term that is considered to be used erroneously after having reviewed the literature regarding the terms under analysis and the definition provided in this study. Employing euphemisms to refer to these items is considered unnecessary and confusing for the reader when the term that best defines them is advertisement or, in any case, paid content, an aspect closely linked to the second hypothesis of the research in which it was pointed out that the inappropriate use of these terms causes them to be presented to the reader in a confusing or unsuitable way.

The remaining 21% are not identified in any way whatsoever, and are mainly affiliate content. Although this is not advertising content in the strictest sense, its identification is considered necessary in some way, as this type of content invites the reader to buy products, bringing a direct benefit to the medium. As a result, there is a need for more in-depth research into affiliate content, as the media industry is increasingly investing in this format as an attractive source of revenue. In the case of ElPaís.com, such content accounts for up to 3% of the items displayed daily on its front page, which are directly linked to the ‘Escaparate’ section created in 2017 (and exclusively dedicated to this purpose), and which indicates an interest in affiliation as a source of income. Moreover, all of the items of branded content, native advertising, and sponsored content (the result of a sponsorship as defined in this study) choose to show the brand in some way on the front page, either with the logo or in a text format.

However, it is important to point out that once inside the items, it is sometimes difficult to identify the typology of each, partly due to the lack of consensus when it comes to defining them and the inappropriate use of some of these terms. In order to make an accurate distinction between the items, which are the subject of this study, a review of concepts such as branded content (Cerezo, 2017; Javier Regueira, 2018) and native advertising (IAB, 2017) has been carried out which, despite being widely studied, are sometimes difficult to distinguish if the terminology is not deeply understood (IAB, 2019).

After having carried out this study, it has been observed that in addition to the differences noted in the theoretical section, another differentiating aspect between the two types of content is their duration over time. While native advertising is more sporadic and temporary, mainly because it is generally linked to the promotion of a specific corporate activity, product, or service, branded content is more long-lasting by nature. A total of 10 of the 14 campaigns registered as branded content remained active during the two month duration of this study, due to the fact that according to both its theoretical definition and the budget forecast pointed out by various digital marketing studies (IAB, 2019), this type of content needs more time to establish emotional links with the audience, become widely known, and amortise its investment (Miotto and Payne, 2019; IAB, 2019). Likewise, more specific definitions are also provided to refer to less developed concepts such as affiliate content, sponsorship, or sponsored content, which are sometimes not used correctly by the medium, as noted in the second hypothesis.

On the other hand, it has been noted that brands choose branded content to bring their values closer to users and try to foster interaction between users and the brand (Maister and Gretzel, 2018; IAB, 2019), with the presence of such content on the front page accounting for 34% of the total number of items analysed.

Furthermore, in the same way as on the front page, brands want to be present inside the item as well. As such, 64% do so with the logo, 20% by integrating the brand name into the text, and 16% by combining both options, so there seems to be no interest on the part of brands or the medium in hiding the origin of this content, as this would prevent them from achieving the main objective of establishing links with users (IAB, 2019).

In terms of subject matter, Education, Technology and Economy are the most common, mainly due to the amount of content provided by the main branded content campaigns that were active during the period of study (Aprendemos juntos by BBVA, El futuro es apasionante by Vodafone, and Think Big by Telefónica), an aspect that supports the aforementioned characteristic of prolongation over time of this type of campaign.

Another important finding that has emerged from this study is that 50% of the items analysed are limited to presenting their content using formats with flat images and text. Branded content is the only one that seems to rely more on attractive content in video format with features that invite the user to interact with the brand, an example of which is Telefónica’s Think Big landing page. This confirmed interest in branded content that is more entertaining and interactive is consistent with the most widespread and accepted definitions of the term (IAB, 2015, Regueira, 2018). It is also true that while investment in branded content has increased by 48% compared to 15% for native advertising (IAB, 2019), it makes perfect sense that this content is more interactive and multimedia, as a larger budget is required for its production. In any case, it is generally accepted that to attract the user’s attention, content with a brand presence should follow digital trends and include more multimedia and interactive elements in its items.

Finally, regarding authorship of this content, it can be affirmed that journalists and media collaborators currently assume a large part of the work involved in the production and publication of these items. At least 50% of the items are written or produced by these professionals, although this study has not determined how many of them belong to the editorial staff and how many are part of the staff of La Factoría, the PRISA group’s department dedicated to producing tailor-made content for brands. It would also be necessary to take into account journalists who have not been counted, but who form part of the remaining 49% who work in agencies or content marketing departments of the brands themselves, also dubiously known as ‘brand journalists’, a term that may be contradictory to the ethics of the profession (Barciela, 2013). These results would validate the third hypothesis and open up a new line of research to find out more about the real functions and opinions of these journalists in order to conclude whether or not they actually carry out these advertising tasks due to the precarious situation in which the profession finds itself (Micó, 2019), as we pointed out in the introduction, or whether, on the contrary, they are simply satisfied with the work they do. In any case, it should be noted that this trend toward linking journalistic activity itself closely to the economic interests of the media in order to increase advertising investment has a direct effect on one of the basic principles of the profession’s code of ethics, which states that it is “contrary to the ethics of the journalistic profession to work simultaneously with advertising” (FAPE, 2017). In this regard, it is generally considered that this trend should be reversed, as it jeopardises the credibility and independence of journalists in the exercise of their profession.

In conclusion, it can be confirmed that a high percentage of brand content is found in digital newspapers due to the importance that this content has attained for their business model. It has also been verified that these items are not always properly identified or distinguished from strictly journalistic content, which may be due to a lack of consensus regarding the terms utilised for this purpose, as well as their inaccurate use, and even improperly identifying items as affiliate content, agreements, or sponsorships. Finally, within this context, journalists in newsrooms are assuming a large part of the work of producing this type of content, although in a way that is ethically dubious, and among such content, the category of branded content has emerged as the most entertaining, attractive, multimedia, and interactive typology of those studied.

6. Index of links to branded content landing pages and sponsored sections

Links to the landing pages of the items that have been counted as branded content or sponsored content, and which were active during the period of study, are provided below for consultation.

Branded content:

Aprendemos juntos (BBVA): https://bit.ly/34Cae1C

El futuro es apasionante (Vodafone): https://bit.ly/34F4sfU

ThinkBig Empresas (Telefónica Empresas): https://bit.ly/3mLWkQO

#EsLaLiga (La Liga): https://bit.ly/2KJAr7s

Pienso, luego actúo (Yoigo): https://bit.ly/2WDcMZ3

Te lo llevas fresco (Carrefour): https://bit.ly/2JiWIsw

Conectando con la grada (Mastercard): https://bit.ly/2WApVSN

Uso Love de la Tecnología (Orange): https://bit.ly/3mC924A

Estar donde estés (Sabadell): https://bit.ly/37EvSV1

Por una inmensa minoría (1906): https://bit.ly/2WDJdqi

Yo también reciclo (Ecoembes): https://bit.ly/37HLDe0

Renault: https://bit.ly/2KrhdUc

Sponsored sections:

Mis ahorros/Mis finanzas (iAhorro): https://bit.ly/38wHXuu

Formación (Emagister): https://bit.ly/3hfmbzp

Mis derechos (Wolters Kluger): https://bit.ly/3hatQz3