doxa.comunicación | nº 32, pp. 405-430 | January-June of 2021

ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978

Frames in 280 characters: a study on the incorporation process of the frames proposed by Folha Online and Estadão.com in the posts of their audiences on Twitter

Frames en 280 caracteres: un estudio sobre el proceso de incorporación de los marcos propuestos por Folha Online y Estadão.com en los posts de las audiencias en Twitter

Carla Tonetto Beraldo has a degree in Social Communication (Pontificia Universidade Católica-PUC), is a specialist in editorial production from the Faculty of Social Communication Cásper Líbero and a Master’s candidate in the graduate program of Communication and Contemporary Culture of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA-Brazil). In addition, she is a fellow of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). She is currently part of the Online Journalism Research Group (GJOL), whose research in the field of journalism in digital networks and new communication technologies has been pioneering since 1995. There, she develops a research, the central theme of which is accessibility to digital media and the responsibility of journalists in creating inclusive content. Directing her gaze particularly to the technology-journalism relationship and how it has changed the classic principles of the profession.

Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Brazil

ORCID: 0000-0002-1526-0265

Alix del Carmen Herrera is a Social Communicator and Journalist, with a focus on communication for social development (Minuto de Dios University, Colombia), a Master’s candidate in Contemporary Communication and Culture (Federal University of Bahia, Brazil) and a member of the Online Journalism Research Group (GJOL) since 2019. She develops a research project on the relationship with audiences within the media that use memberships as a business and editorial model. She is a fellow of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Brazil.

Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Brazil

How to cite this article:

Tonetto Beraldo, C. y Herrera, A. C. (2021). Frames in 280 characters: a study on the incorporation process of the frames proposed by Folha Online and Estadão.com in the posts of their audiences on Twitter. Doxa Comunicación, 32, pp. 405-430.

Received: 08/20/2020 - Accepted: 03/14/2021

Early access: 11/04/2021 - Published: 14/06/2021

Abstract:

This article aims to seek connections between the discourses of Folha Online and Estadão.com and the discourses in the posts of their audiences on Twitter around a controversial political event which took place in Brazil in 2019. The discussion arises in a context marked by political affections, strongly established within the Brazilian people after controversial episodes widely reported by the press, ranging from a general mistrust of the media to an energetic defense of individual political positions. Adopting a qualitative and quantitative methodology, we use keywords as units of analysis, and consider both the frequency in the use of those words and the framing function that each one exerts. The results show a relationship between the frames proposed by the media and those used by the audience, but these vary according to each function suggested by Entman (1993).

Keywords:

Framing; Twitter; media discourse; social media.

Recibido: 20/08/2020 - Aceptado: 14/03/2021

En edición: 11/04/2021 - Publicado: 14/06/2021

Resumen:

Este artículo tiene como objetivo buscar relaciones entre los discursos de Folha Online y Estadão.com y los discursos en los posts de sus audiencias en la red social, Twitter, entorno a un evento político polémico, que tuvo lugar en Brasil en 2019. La discusión surge en un contexto marcado por afectos políticos, establecidos fuertemente en el pueblo brasileño después de episodios controvertidos y ampliamente divulgados por la prensa, que van desde una desconfianza general en los medios de comunicación hasta una defensa enérgica de las posiciones políticas individuales. Adoptando una metodología cualitativa y cuantitativa utilizamos palabras clave como unidades de análisis y consideramos tanto la frecuencia en el uso de palabras como la función de encuadramiento que cada una ejerce. Los resultados muestran una relación entre los frames propuestos por la prensa y los utilizados por el público, pero estos varían según cada función sugerida por Entman (1993).

Palabras clave:

Encuadramiento; Twitter; discurso mediático; redes sociales.

1. Introduction

Currently, much of what Brazilians know about politics comes from social media. According to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020, it is the first time, since 2013, that social networks have overtaken television as a medium for the consumption of news in the country (Newman et al., 2019). Thus, digital spaces are now a common and obligatory place for journalism, from where it is proposed to provide interpretations of the world (Brüggemann, 2014) to the public opinion.

This point coincides with the initial idea of framing,1 the perspective of which analyzes the way in which the media present a specific event in their reports and give relevance to or omit certain information. In 1922, Walter Lippman, in his work Public Opinion, mentioned the essence of the model: “[…] the media, our window to the vast world beyond our direct experience, determine our cognitive maps of the world” (McCombs & Reynolds, 2002, p. 2). More specifically, “the central logic of framing is that journalists construct symbolic representations of society that the audience uses to give meaning to events and problems” (Bronstein, 2005, p. 785). Following both perspectives, we recognize keywords as symbols2 and units of meaning that are transmitted through journalistic messages.

In this sense, studies on framing have favored a “[…] mediacentric perspective. (López, 2010). In other words, research on framing has focused on the way in which the media construct frames and, to a lesser extent, how they are inserted into social contexts, including how frames proposed by other types of organizations (e.g., political groups, social movements) are adopted by the media.

With that in mind, the purpose of this article is to understand the operation of the frames proposed by the newspapers Folha Online and Estadão.com in relation to the cut of funds for higher education carried out by the Brazilian government in 2019. In this way, we seek to see if such frames were received by their audiences and incorporated into their discourses on Twitter; likewise, we intend to check which aspects were frequently highlighted. Furthermore, our analysis considers the context of political polarization unleashed in the first six months of the government of the current president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro. In it, we highlight the measures adopted by the Ministry of Education (MEC), which were the subject of several controversies that drew the attention of the media and of the public opinion.

During the aforementioned period, MEC’s decisions were marked by debates over events such as changes in the entity’s governing body, cuts in funds allocated to federal universities, problems with the Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Studies and Research (INEP), tensions over the expiration of the contract, in 2020, of the Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and Valorization of Education Professionals (FUNDEB), among other controversies. While this investigation was being carried out, the economist Abraham Weintraub was the second minister in charge of MEC since the beginning of the new government; the first officer was Ricardo Vélez Rodríguez. The scenario, marked by the restriction of expenditures, as well as by opposing statements and positions among public opinion, increased the strain between the government and the opposition, therefore, this work was carried out in such a context of political “high temperature”. In this investigation, we concentrate the analysis around the cut of funds to federal universities, “[…] since each subject has its dynamics of time. Examining more than one topic at the same time can be problematic” (Eyal, Winter & De George, 1981, p. 216).

By focusing on the frames used by Folha Online and Estadão.com in the articles published on the subject and shared on Twitter –in addition to the acceptance of these frames in the audience comments on the same platform–, we intend to advance in the understanding of the frames transmitted in these publications and identify the aspects highlighted by the press and replicated by readers in their tweets. Given the importance of frames in political communication, we also examine whether the identified frames fulfill any of the four main functions indicated by Entman (1993): definition of specific problems, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and recommendation of treatment of the topic described.

To carry out the research, we collected articles and posts from the official accounts of the newspapers on Twitter related to the cutting of funds to federal universities. The selected period was from April 30, 2019, when the measure was announced, to June 30 of the same year. According to Wolf (2012, p. 175), “[…] the issues vary in relation to the time needed to place them in a relevant position in the public opinion”. Therefore, we opted for a two-month period for data collection; a sufficient interval for the consolidation of a public debate. According to some elements of the methodological proposal of Zhou and Moy (2007), we compared the frames of the media and the frames in the audience’s responses, based on the selection of keywords, resulting from the search on the platform using the TweetDeck tool, in the period delimited for the analysis.

At the end of the text, we present the results on the acceptance of the frames proposed by the media, in public discourses on a platform such as Twitter, within the framework of a situation with the necessary conditions to create a broad debate. We also discuss the implications in the Brazilian context, the variables in each newspaper, and the possibilities of studies on framing and some of its particularities in digital public debates.

1.1. Theoretical foundation

Research in the field of communication raises several conceptual and methodological problems, while proposing solutions to specific problems by integrating various disciplines (França, 2012). In fact, media effects studies raise epistemological challenges that belong to the field of communication. In particular, it is necessary to understand the heterogeneous theoretical perspectives that “[…] alternate, coexist, and complement each other” (Wolf, 2012, p. 137) in the academic discussion on framing.

Based on this multiplicity, it is a sine qua non condition to address the hypothesis of agenda setting and to review the theoretical limits of the relationship between framing and agenda setting, in order to contextualize their overlapping and explain the particularities of each perspective. Indeed, treating them separately is a response to the fact that “[...] the meeting of these studies [...] has created contradictory conclusions about the power of media frames over the audience and the setting of issues on the audience’s agenda” (Colling, 2001, p. 92). According to Scheufele (2000), there are substantial differences between both concepts,

[…] given that agenda setting works under a causal approach, in which the frequency and number of times with which an issue is disclosed by the media interferes with its position on the public agenda and, therefore, the design and the methods applied in these studies are apt to understand this causal correlation (p. 46).

The perspective that the media select the issues that stand out in the public opinion represents the first level of agenda setting (it refers to objects, that is, the choice of topics that will make the news). At the second level, also called attribute setting,3 the focus is on how these issues are submitted to the audience at different times. While agenda setting is related to the contemporary concept of framing, one cannot assume that the latter is contained in the former. In the words of Rossetto and Silva “[…] framing enriches the research of the effects of the media, especially agenda setting, however, it is often confused with its second dimension” (Rossetto & Silva, 2012, p. 99).

Hence, as it is constantly and inadvertently suggested as a synonym for the second level of agenda setting, a clear delimitation of the concept of framing is necessary for the purpose of this article. First, we understand that framing is the way in which events are interpreted in a news story. In this regard, Carragee and Roefs (2004) problematize the reduction of framing to topics and attributes for two main reasons: first, this perspective does not take into account the way in which certain frames are applied to different themes; second, it ignores how the posting of a single subject can be the product of more than one frame. Therefore, we prefer the approach given by Erving Goffman.

I assume that the definitions of a situation are constructed in accordance with the organizing principles that govern events –at least social– and our subjective involvement in them; frame is the word I use to refer to those basic elements that I can identify. That is my definition of frame (Goffman, 1986, pp. 10-11).

From there, the frames structure which fragments of reality can become news (Koenig, 2004). Thus, agenda setting refers to the selection and highlighting in published articles (object), while framing refers to the selection and highlighting of published terms (publication attributes) (Scheufele, 1999).

Therefore, it supposes an interpretive process that, according to Wolf (2011), “from the ‘imposition’ of an interpretive framework of what has been intensely covered” (p. 117). The academic explains that frame analysis” [...] was incorporated into journalism studies and resulted in the current framing hypothesis.” In which, according to Park (2003), the press is responsible for building a certain understanding of reality that works like a window frame. Metaphorically, it is through it that public opinion will come into contact with a given reality –partial or not –and this contact will depend on how open is said window (apud Leal, 2007, p. 145).

Methodologically, in a bibliographic review, Pozobon and Schaefer (2014, p. 157) identify two critical points related to researches about framing: “[…] conceptual uncertainty and lack of methodological systematization of the research”. In terms of empirical research, this means keeping the advances of the model disaggregated. Previously, López Rabadán (2010) had reviewed the last two decades of framing studies and identified a dominant perspective where “[…] the media activity itself becomes the object and central axis of these studies” (p. 236). This could be pointed out as the meeting place between the framing of social experience proposed by Erving Goffman (1986), the framing of news stories by Mauro Porto (2004), as well as the reflections on framing by Robert Entman (1993).

Precisely, the work of the Brazilian researcher Mauro Porto contributes to clarify the relationship between framing and political thought –the sphere within which our object of study is located –for him, “[…] frames are important constitutive elements of narratives and the process by which we give meaning to the world of politics” (Porto, 1999, p. 14). Hence the importance of words as primary units in the construction of media narratives and consequently in the establishment of key meanings for the reading of any socially or journalistically relevant fact.

Frames draw attention to some aspects of reality while obscuring other elements, which can lead the audience to have different reactions. Politicians seeking support are forced to compete with one another and with journalists through news frames (Entman, 1993 p. 4).

By the way, the development of studies on news framing has also attracted the attention of academics, Valera (2016, p. 26), for example, denounces “the growing divorce of international research on framing from its first sociological roots”. After a thorough review of literature, the researcher assumes framing as “[...] a research model capable not only of determining the journalistic frames and their effects on the audience, but also of accounting for the constructed and conflictive nature of the public discourse, placing the study of journalistic messages in the context of the multiple ideological disputes that occur in the public space” (Valera, 2016, p. 26).

In fact, the author proposes that one should overcome the mediacentric bias, which until now has defined framing research, by recovering the sociological basis within communication studies. Which means, directing the analysis of the media frames, considering the particularities and influences of the social context (Valera, 2016, p. 25). In line with Recuero (2016), we assume that the public sphere constituted within Twitter is traversed by power relations that influence the dissemination of certain messages to the detriment of others. These relationships are also linked to offline space disputes. Something that has been better observed from a sociological perspective.

In 1999, Scheufele published an article in which he compiled twenty-five years of studies on framing, distinguishing four processes around which the research was developed. The first one refers to the construction of frames in communication with the help of “external” influence. A second process focused on how these communication frames “were established in frames of thought and the exact work in the psychological process.” The third one mentioned the influence of “citizen actions” and social movements on journalists during the frame-building process. The fourth process, on the other hand, focuses on the impact at the individual level, that is, “on later thinking and behaviors or attitudes” (Chong & Druckman, 2007, p. 51).

Later, in 2005, after reviewing the theory and typology of news framing, Claes H. De Vreese (2005) confirmed that “[…] an influential way for the media to shape public opinion is to frame events and topics specifically” (p. 56). The researcher distinguishes two types of approaches in the framing hypothesis: (1) the inductive one, which “[…] refrains from analyzing news with previously defined news frames. The frames emerge from the material during the course of the analysis”; and (2) the deductive one, which “[…] investigates which components of the frames are defined and operative before the research. And what elements of a news story constitute a frame” (De Vreese, 2005, p. 56).

From an inductive approach, framing “must be commonly observed in the journalistic practice” (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997, p. 72). On the other hand, from a deductive perspective, academics pointed out the importance of observing the presence or absence of certain keywords (Entman, 1993) and of the choice of language, citations, and relevant information (Shah et al. 2001). As a result, they developed studies on framing that address different levels of the process of construction and establishment of frames as “interpretive packages” (Gamson & Modigliani, 1989). Specifically, it is this perspective that supports the work with keywords as basic interpretive units in short discourses in the style of the microblogging platforms.

In this regard, in the context of digital communication and social media platforms, some essays have set out to understand how framing works, which – unlike traditional media – provide the possibility of expressing ideas in real time. In 2007, Zhou and Moy conducted a study on framing processes and the interaction between online public opinion and media coverage, where they assessed the relationship between the structure of the media –in a sociopolitical event in China–and the reception of these frames in the public opinion on Twitter. As a reference, they used the research of Chong and Druckman (2007) on frames in specific competitive environments; the authors argue that there are different perspectives on a topic from which the same topic can be framed. The question, then, is to evaluate which of these “competing frames” will be adopted by the public opinion (Chong & Druckman, 2007). The researchers highlighted the elements “quantity” and “strength” so that one or the other frame could be adopted: the term “quantity” refers to frames with many repetitions, while the “strength” variable is associated with the source’s credibility. (Druckman, 2001). In this sense, the effect of a frame could be determined by one characteristic or the other.

However, research on framing in digital environments faces many of the typical setbacks of traditional studies, precisely because of the absence of a research paradigm. For D’Angelo (2002), establishing such a paradigm in framing research would allow those who study it to:

(a) share definitions of core concepts, (b) agree on the most useful theoretical statement on the relationship between these concepts, (c) develop relevant hypotheses and research questions, and (d) agree on the research methods and instrumentation to collect and analyze data in the most appropriate manner (D’Angelo, 2002, pp. 871-872)

In response to the needs of this study, it was necessary to take, as a starting point, the work of Chong and Druckman (2007), which shows that the effect of framing occurs when communication increases the “weight” of a new or existing belief in the formation of the general social attitude. In this sense, it is possible that a given topic with wide coverage is more accessible in the individual’s mind and has a greater effect on their opinion (Chong & Druckman, 2007).

For the case analyzed in this article, we have two positions: on the one hand, that of the then Minister of Education of Brazil, Abraham Weintraub, who –in an announcement in 2019– reported on the cutting of funds to federal universities that “did not perform satisfactorily and promoted disorder on their campuses”4. This event triggered statements and demonstrations against the government throughout Brazil. On the other hand, students, teachers, federal university officials, and education advocates reacted to the measure, which drew attention because it meant a reduction of more than half of the budget imposed on other public educational institutions. Later, this reduction was extended to all federal universities in the country, initially announced as 30% of the total budget and later as 30% of the so-called discretionary budget (that is, non-mandatory spending), corresponding to approximately R$1.5 billion. Universities rejected the measure and defended the importance of scientific research and free public education. Based on the above, we formulate:

Hypothesis 1: The keywords of Estadão.com and Folha Online show a homogeneous discourse during the analysis period, which contributes to the acceptance of their frames by the audience.

In the study of the Qiangguo Forum in China, Zhou and Moy (2007) organized the method in three phases to test the relationship between the frequency and the acceptance of a frame, correlating media coverage and online opinion with the functions suggested by Entman (1993):

After a complete review of the matter, the interviewees were asked to choose which of the four functions of Entman’s frames –(F1) problem definition; (F2) causal interpretation; (F3) moral evaluation, and (F4) treatment recommendation–was the main function, and determined what specific structure was used to fulfill this function. (Zhou & Moy, 2007, p. 86).

The research developed by Zhou and Moy (2007) deepened the understanding of the construction and establishment of frames in digital environments, specifically on social media platforms. In fact, the report by Latinobarómetro (2018)5 –a non-profit organization that conducts periodic public opinion surveys in Latin America– corroborates the idea that social media platforms make it easier for citizens to exercise their freedom of expression to the full extent. In the aforementioned document, Twitter ranks third among the most used social networks on issues that affect democracy among the Latin American public. For framing studies, this represents a fertile field in which to explore the efficiencies of framing in an environment where, in addition to being suitable for political debate, not only news frames are present.

The study also approached the subject based on an interaction process from which sets of frames are built that reinforce the way of interpreting and giving relevance to a certain aspect of the news. Given that Brazilians are among those who use social networks the most in the world (Newman et al., 2019), it is relevant to highlight that the action of President Jair Bolsonaro on such platforms has a strong influence on public opinion. Given in particular by the context of political polarization unleashed in Brazil after the removal of former president Dilma Rousseff in 2016, and the election of the current president. Thus, the funding cuts to federal universities in 2019 would not go unnoticed by the public opinion or the press. Therefore, considering both the contribution of the authors and the political context in Brazil, we present the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Due to the polarization scenario in Brazil, the online public will more easily adopt in their Twitter posts the keywords related to the functions of causal interpretation (F2) and moral evaluation (F3) presented by the media.

Next, we present the methodology used for the collection and interpretation of the research’s data, as well as the results obtained.

2. Methodology

The research was configured with an exploratory and quantitative-qualitative approach6. In order to reach the complexity of the object of study and to understand the sociocultural dynamics that permeate this research, we propose a multidimensional view that uses the strategy of methodological triangulation as a possibility to build coherence and cohesion. Denzin and Lincoln (2006) clarify that “[…] using multiple methods, or triangulation, reflects an attempt to ensure a deep understanding of the phenomenon in question” (p. 19).

Thus, the investigation was carried out in three stages. The first was a review of the literature: we identified previous researches that approached Twitter as a workspace and that could help us to understand the role of framing in this social network. The second phase included a review of the articles published by Folha Online and Estadão.com during the time determined for this study, to then carry out a content analysis. Finally, we carried out an empirical research in order to test our hypotheses based on the relationship between media frames and the opinion of readers on Twitter on the subject, using keywords.

The article was restricted to the way the press handled the fact that funds for higher education in Brazil had been cut. The objective was to test our hypotheses based on the relationship between the media frames and the opinion of the readers on Twitter on the subject, using keywords.

We defend the choice of the corpus formed by the tweets of the newspapers Folha de São Paulo and Estadão because they are two newspapers with a large audience and national credibility, with different editorial lines. We adopted the definition of an editorial line by José Marques de Melo, one of the seminal authors in the field of investigative journalism in Brazil, who states:

[…] selection means, therefore, the perspective through which the newspaper company sees the world. This vision is based on what is chosen to be published in each edition, privileging certain themes, highlighting certain characters, obscuring some and omitting many (Marques De Melo, 2003, p. 75).

Historically, Folha and Estadão have not only maintained leadership among the most consulted media in Brazil but have also represented dissimilar positions in relation to political and social realities, as we will see later. Controversial issues such as the decriminalization of abortions, the legalization of marijuana, and the death penalty, for example, are addressed by Folha de S. Paulo to fit in with a more liberal vision of society. In turn, O Estadão de S. Paulo expresses more conservative approaches to the same topics.

Besides the fact that the positions of these two media outlets are opposite, the fact that both have writing manuals in which they indicate the journalism they intend to practice and that are a reference in the undergraduate courses in journalism at Brazilian universities was another selection criterion. In these, each medium is presented as pluralist, independent, and nonpartisan. However, this proclaimed neutrality is not always found, as shown by Agostinho and Lannes (2008). As the authors of Folha de São Paulo write:

[…] this general manual is not a replacement for a journalism course, and certainly not a substitute for the practical experience of writing […]. Its objective is only to translate, in simple and empirical rules, the concept of newspaper that Folha seeks to practice. (Folha Manual, 1984).

For its part, Manual de Redação de O Estado de São Paulo, launched in 1990, lists, in addition to the behaviors that journalists must adopt when writing a text, the need to avoid words or expressions that may create doubts or be interpreted as ambiguity by the reader (Oesp Manual, 1990).

In the same way, we understand that online versions are more suitable to test our hypotheses since they maintain the aforementioned assumptions and also reported a 33% increase in digital subscriptions of those media that have web editions compared to 2018 (Newman et al., 2019). Therefore, content analysis is appropriate in the context of research on framing, since “[…] the method assumes a critical reading of the meaning of the messages, their manifest or veiled content, i.e., what is said and what is implicit or even disguised” (Bonone, 2017, p. 84). Based on a content analysis, we define the units of analysis and the categories into which they were divided.

As for the empirical research, it was carried out in three stages. First, we define topic and periodicity, and then compile the articles on the Folha Online and Estadão.com websites. We then use the TweetDeck7 tool to find the posts of these stories on the Twitter accounts of both media. We did the same with audience tweets, and we considered both the topic and the periodicity. In this, we count, identify, select, and parameterize the posts, to establish categories of keywords according to the four functions of the frames listed by Entman (1993): problem definition, casual interpretation, moral evaluation, and treatment recommendation. Finally, we tabulate the data for the number of repetitions to test the hypotheses.

2.1. Delimitation of the topic and collection of articles

In the first compilation, we used each media outlet’s search engine to filter and select articles that dealt with funding cuts in federal universities. The keywords used were: corte de verbas; universidade federal; universidade; corte; UFs; bloqueio; Abraham Weintraub; orçamento; balbúrdia; ministro; educação; MEC; and Ministério da Educação [cutting of funds; federal university; university; cutting; UFs; blocked; Abraham Weintraub; budget; brouhaha; minister; education; MEC; and Ministry of Education]. By adding the two media, we found 214 articles published between April 30 and June 30, 2019. The first date was defined by the announcement of the interim measure on funding cuts of federal universities. Regarding the end date, and in accordance with the recommendations of the Recuero and Zago study (2009), the more visible a particular sender of a tweet is, the greater the recirculation of the same topic. Thus, even with the number of people who reach the publications of Folha and Estadão on their Twitter accounts (5.7 million and 6.9 million followers, respectively), it was necessary to consider both the engagement level and the multiplicity of content to which users are exposed in said social network. Then, the period to obtain effective results could not be less than two months. The compilation included only informative articles, special reports, and notes. In this, we exclude opinion articles, letters from readers and columns. Therefore, by adding materials from the websites of both newspapers, we obtained 154 articles to examine.

We then use the same keywords in the TweetDeck search engine to find posts associated with these articles. We obtained 78 posts for Folha Online and 80 posts for Estadão.com, adding 158 publications related to the cutting of funds of federal universities in the mentioned period. As a way to specifically verify posts on Twitter, we considered both the content of each tweet and the lead of the article. Here we exclude the title, as it often matches the content of the post and does not provide additional information.

2.2. Selection and parameterization of the results

From the 158 posts found on Twitter corresponding to the 154 articles previously referred and filtered on the websites of both media, we identified the most used words both in the news leads and in the text on the Twitter post, through the Online Word Counter software.8 We listed 345 words with at least two repetitions. We selected the first 110 words with the most repetitions (excluding articles and connectors) and we only worked with those that referred to the debate and, therefore, were susceptible to framing power9 (Entman, 1993). After this filter, we considered 70 words in Folha Online and 93 words in Estadão.com.

Again, we used the TweetDeck tool, with the same filters used to identify the articles, to find the tweets of the audiences of these media. We distinguish three categories of tweets: a) responses to the posts of articles published by newspapers; b) tweets that mentioned or tagged the newspapers or c) tweets in which the link of the article was directly shared from the website.

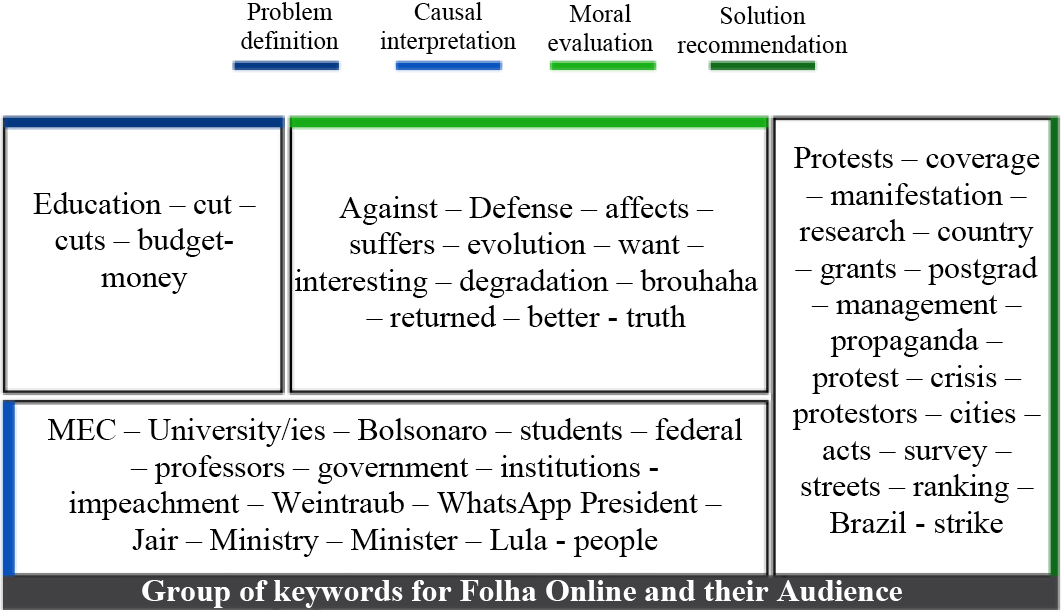

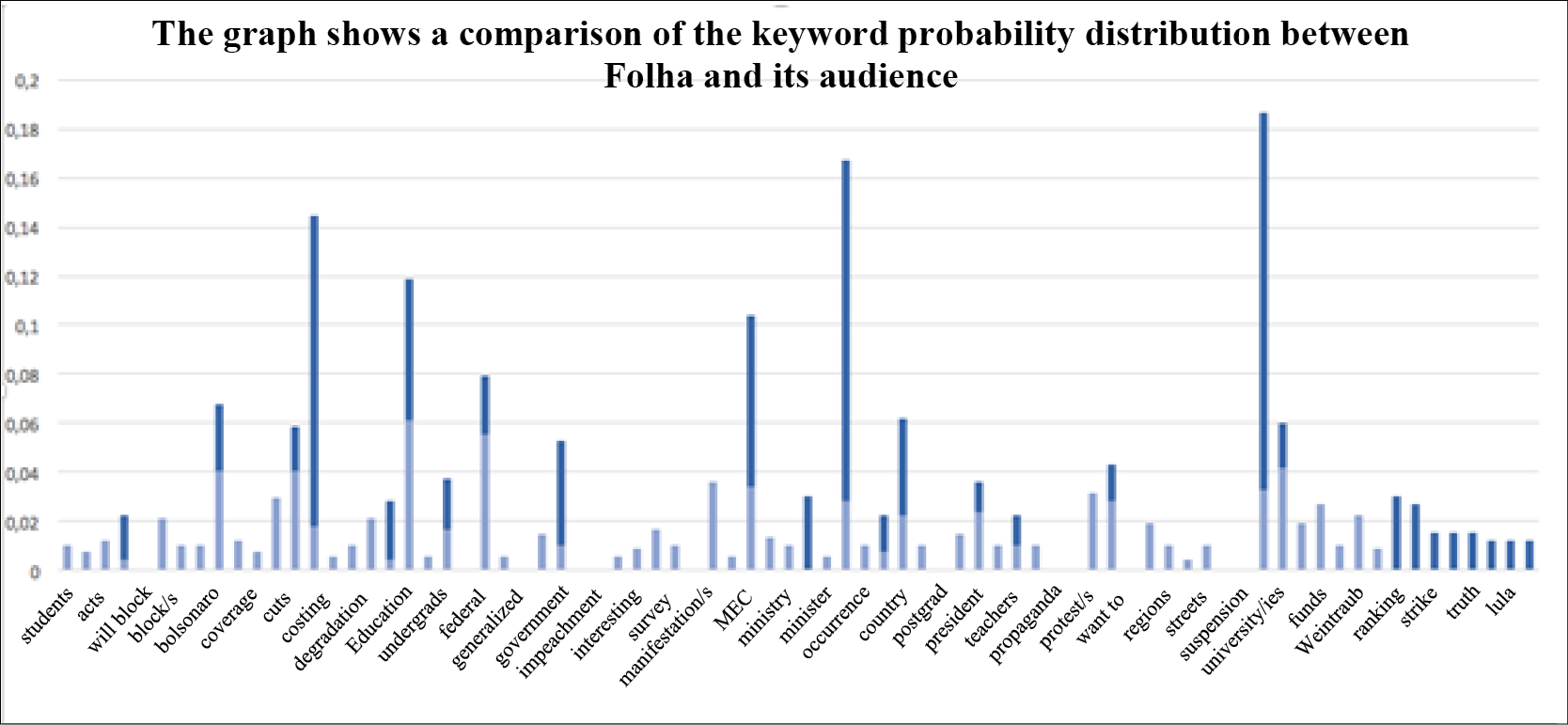

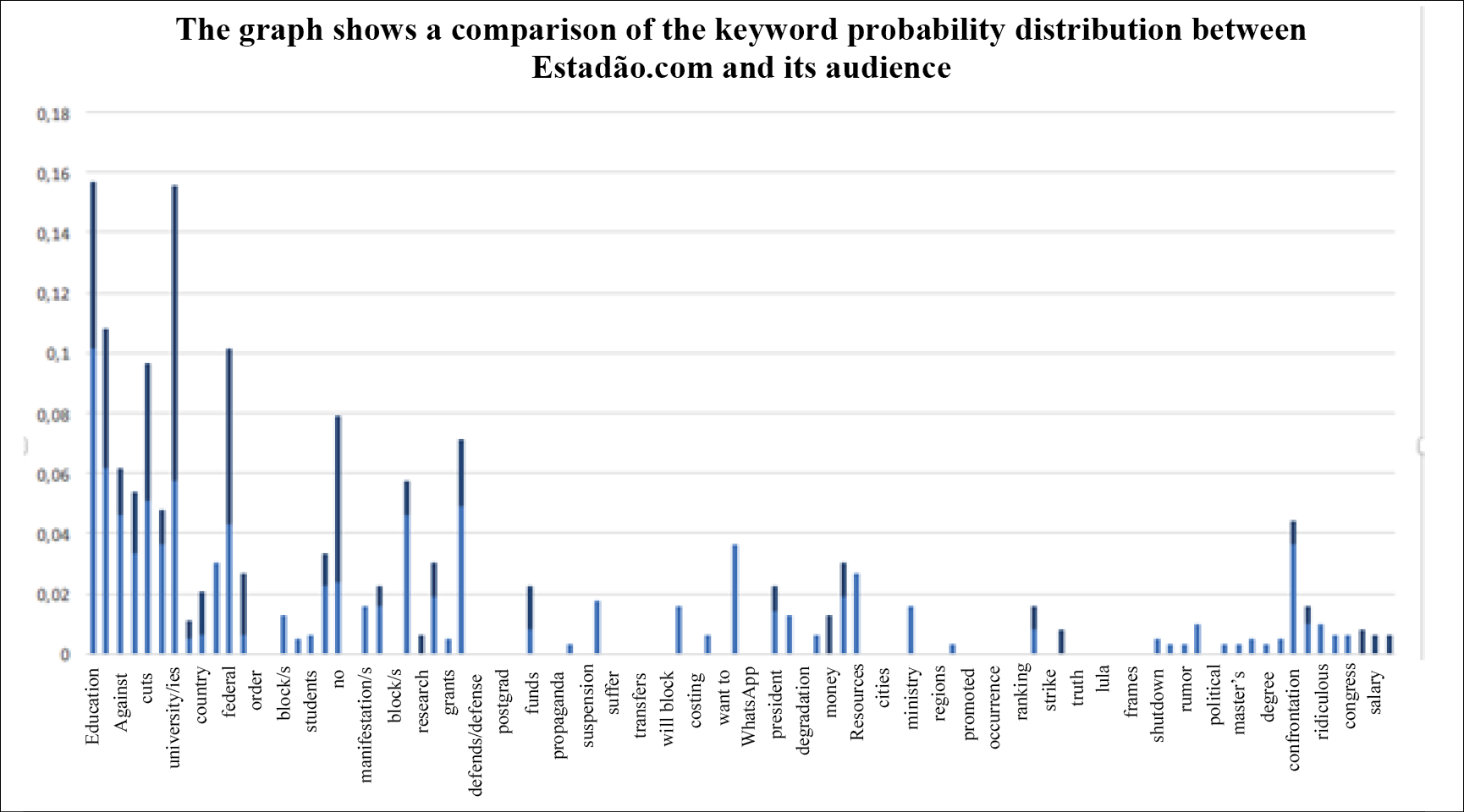

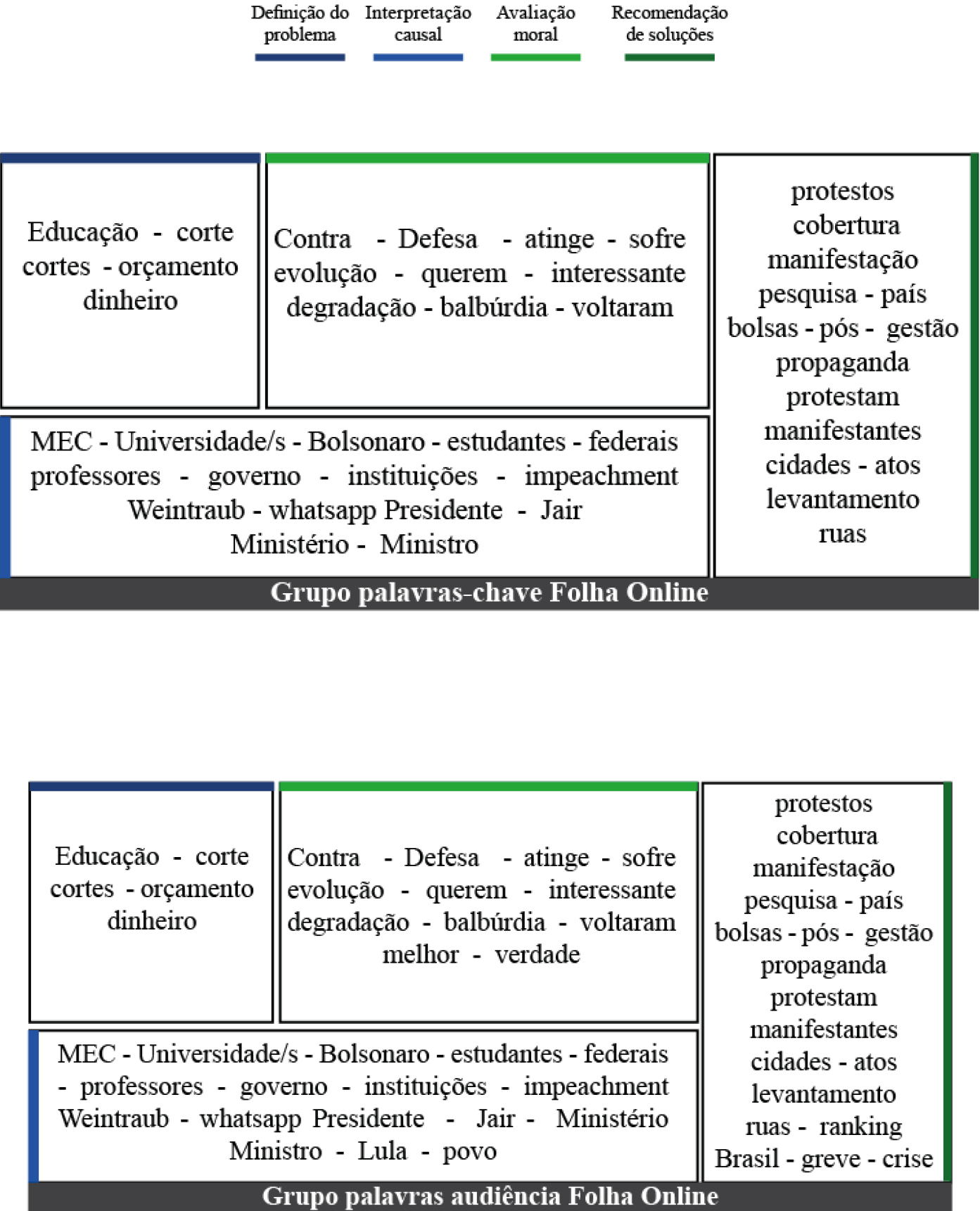

Following data collection, to verify the posts of the audiences of each medium, we carried out an identical procedure when examining articles from Folha Online and Estadão.com. We started with a word count, selected the 110 words with the most repetitions, and excluded articles and connectors. The words collected were 78 in the tweets of the audience of Folha Online and 96 in the tweets of the audience of Estadão.com. In a first projection, we made a probability distribution by comparing the use of words according to each source or author (newspapers and audiences of each medium) as explained in Figures 1 and 2. We use at least one keyword to define each function.

Figure 1. Group of keywords published in Folha Online and in the tweets of its readers

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

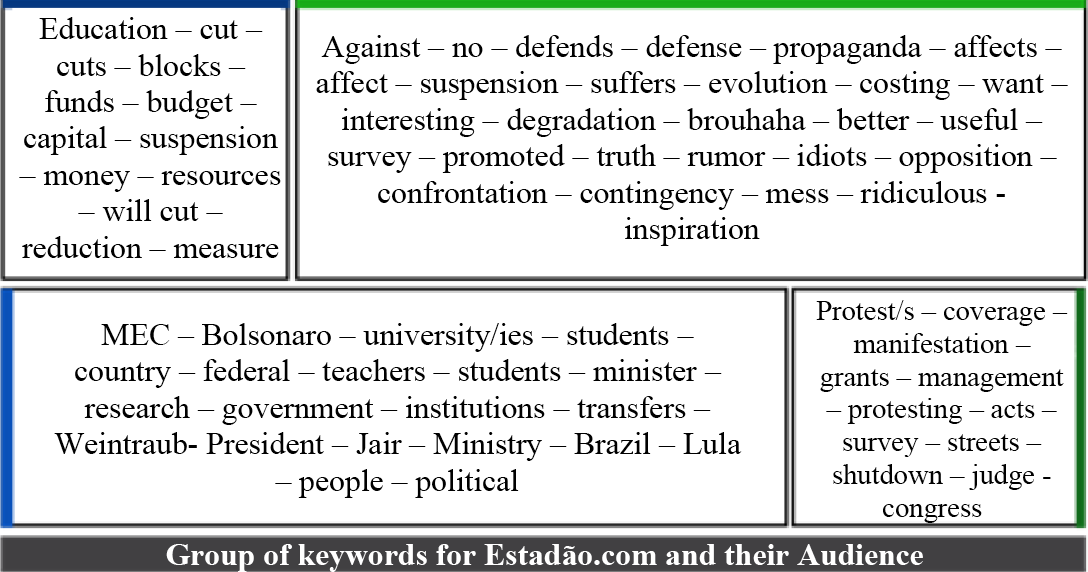

Figure 2. Group of keywords published in Estadão.com and in the tweets of its readers

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

2.3. Categorization of keywords according to framing functions

After identifying a similar distribution between the highlights made in the Estadão.com articles and the opinion of its readers in the tweets, we sought to understand more specific relationships. Therefore, we categorize the words of each newspaper and those of its audiences into four groups. The criterion was the correspondence with any of the four functions of the frames; this classification included both the number of repetitions of each term, as well as the contribution that each term made to the debate. In other words, what aspect of the issue at hand was addressed or defined by a particular actor. We counted the total number of repetitions in the groups (according to the function) and obtained the percentages in relation to the total sample. From this percentage number, we verified the match between each author of the post (media and audience) and the nominal variable determined, in this case, the functions of the frame. Then, we cross-referenced the percentages of keyword usage between: (a) the two newspapers; (b) the two newspapers and their respective audiences; and (c) the audiences of both newspapers. We plotted the data in line graphs to identify significant meeting points in the results obtained (see results).

By making a distinction between the author of the post and word usage that might involve problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and treatment recommendation (Entman, 1993), we sought to test our hypotheses. These are based on the assumption that, in a polarized political situation, the framing functions that appear in media discourses are also enhanced in the opinion of the Twitter audiences of said media. After a compilation of results, and the submission of the corpus and the methodological process that resulted in the selection of this content, we proceed to filter the content analysis.

2.3.1. Content analysis

We use elements of the methodological model established by Zhou and Moy (2007) to evaluate the effect of media framing on Twitter comments. The units of analysis in framing studies are varied; This can include a word, a metaphor, an example, a slogan, a representation, or an image (Gamson, & Modigliani, 1989); a paragraph (Akhavan-Majid, & Ramaprasad, 2000); or a newspaper article (Callaghan, & Schnell, 2001; Yang, 2003). Here, the units of analysis were the keywords. We considered, for each medium, the words that involve any of the four framing functions established by Entman (1993), according to the reasoning that we explain below.

2.3.2. Problem definition

To define the nature of the problem related to the event described, the audiences and the media used one of the two perspectives raised: in the first, the cutting of resources was emphasized as a factor that impacts Brazilian education as a whole, reiterating the need for public, free, and good-quality education. Second, the activity of the federal universities was investigated and questioned; At this point, the balbúrdia10 [brouhaha] and the alleged lack of commitment of the students of these institutions stand out (attributing the need for the government to act in the face of the situation). Thus, we considered words that articulated with one of the two positions mentioned above and that answered the question: What is happening? In other words, we seek to “[…] determine what a causal agent is doing, with what costs and benefits; generally measured in terms of common cultural values” (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

2.3.3. Causal interpretation

Tweets and news stories also tended to attribute the event to various factors. The structure of the media suggested three main causal factors: the government is unaware of the country’s educational problems, social inequality is a privilege to the rich and not the poor, and the “balbúrdia” and the lack of commitment by federal universities motivate the cuts. In this function, we include those words that mentioned actors or causal elements: - What/who is causing the problem? That is, the effort was “to identify the forces that create the problem” (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

2.3.4. Moral evaluation

Given the political nature of the situation, the moral evaluations of the event and the actors expressed in the posts on Twitter recalled the need for good-quality public education, while discussing the lack of commitment of the students to education. Likewise, they emphasized the role of the media and the public opinion in the “supervision” of the minister of education and in evaluating the current government’s management with respect to education. We included in this function words that answer the following question: - How to qualify the situation? Or, in other words, what terms were used to “judge the causal agents and their effects” (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

2.3.5. Solution recommendation

Most of the frames suggested solutions for good-quality public education and emphasized the need for educational reform, or even encouraged changes in the government structure. Others demanded civil actions in support of some of the currents to face the situation. In this function, we considered those words that answered the questions: - What can be done? What effect and impact will the measure have? That is, those who sought to “offer and justify treatments for the problem and predict its possible effects” (Entman, 1993, p. 52).

2.4. Quantitative variables

In addition to the nominal variables, the study considered as a quantitative variable the reiteration that the press gave its articles on the subject. The measurement was made effective through the frequency (%) of each frame11 congruent with the existence of keywords in the articles of Folha Online and Estadão.com and in the responses of the users in their tweets. With this and other variables, we make four correlations. The objective was to examine whether the opinion of Twitter users on the subject is associated not only with a type of frame function, but also with the intensity of the use of words in this category in media coverage. We further this discussion in the results.

3. Results

We aimed to identify both the similarities and the differences in the discourses on funding cuts in higher education in the newspapers Folha Online and Estadão.com, as well as the acceptance of the frames proposed by the media in the opinion of users in their tweets. Taking into account that the writing space on Twitter is only 280 characters –in addition to the platform’s update speed– we concentrated the analysis on keywords as a starting point for the analysis to understand these frames on the social network.

A first experimental test showed us a probability distribution of the most used words in each conduit, during the two months of data collection, in relation to its audiences. There were some points in common in the descriptive words about the problem in the two newspapers, although they were distant in the proportion of use, as shown in Graphs 1 and 2.

Graph 1. Keyword probability distribution among Folha Online (light blue) and its audience (dark blue)

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

Graph 2. Keyword probability distribution among Estadão.com (light blue) and its audience (dark blue)

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

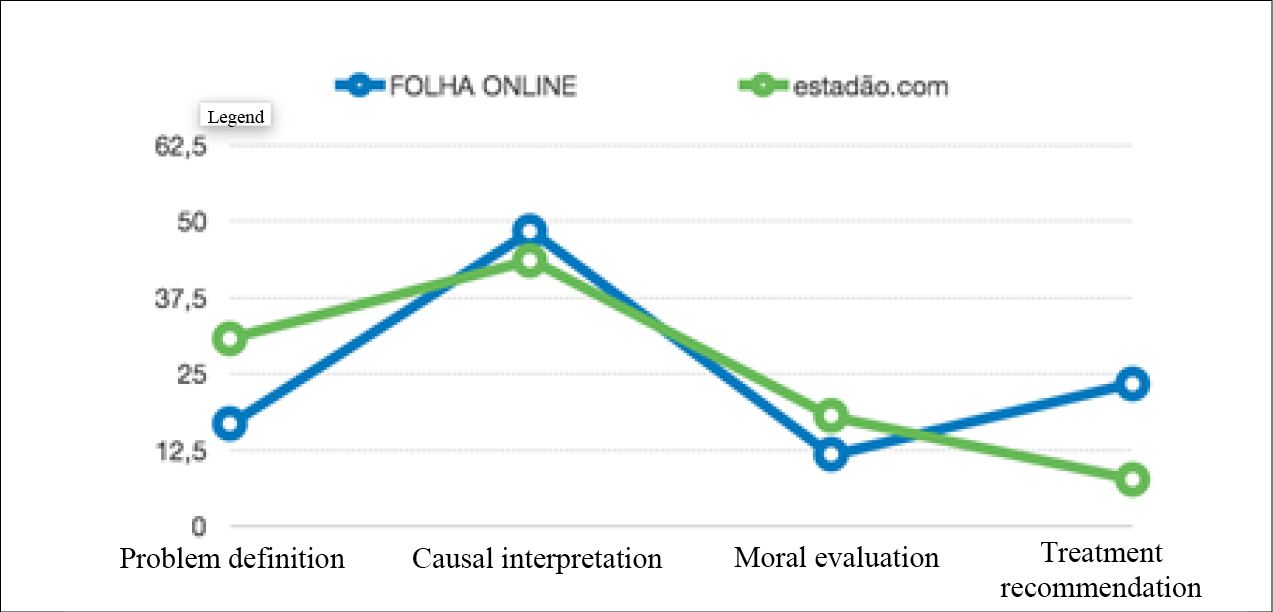

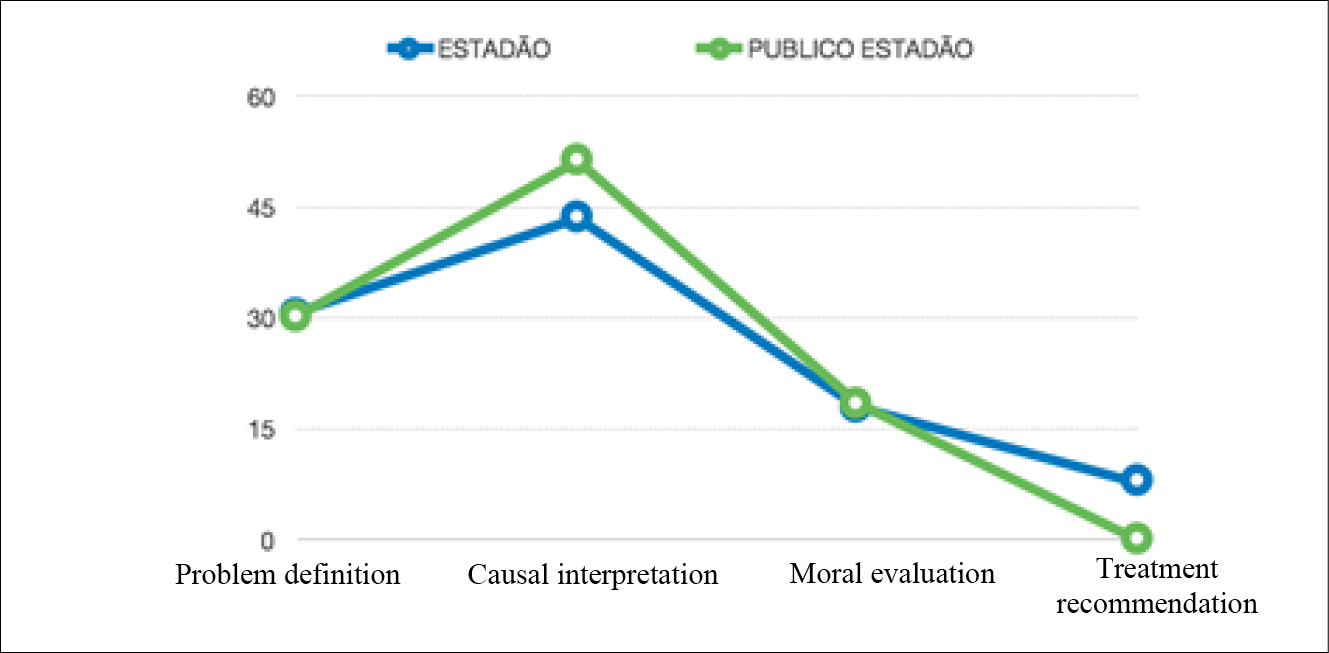

Based on the above, our first hypothesis stated that there would be an approximation between the discourses of Folha Online and Estadão.com and that this would favor the acceptance of the frames in the opinion of their audiences (H1). After pointing out the words in each function of the frame, we crossed the percentages of use of each group of words in the respective media. Both followed a similar line (with respect to percentage of use) only in the second and third functions of the frames (causal interpretation and moral evaluation). In this evaluation, Folha Online had 48.29% and Estadão.com had 43.51% of words that evoked the causal agents of the problem. Regarding the moral evaluation, both used similar words that judged the cuts in funds or any of the parties involved in the process: 11.74% in Folha Online and 18.06% in Estadão.com.

In the other two functions of the frames (definition of the problem and recommendation of treatment), we observed that the corresponding words were used in a different proportion in each newspaper, with a percentage of 16.66% in Folha Online to define the problem and 30.70% for Estadão.com in the same role. Regarding treatment recommendation, Folha Online used 23.29% of words related to issues of problem treatment and possible consequences compared to Estadão.com, which used only 7.71% (see Graph 3).

Consequently, the first hypothesis (H1), which anticipates a more or less homogeneous percentage line, is partially confirmed, since the points of similarity in the discourses of both are only close in two of the four functions of the frames used as nominal categories. This also shows us that Estadão.com used more words that tried to define the issue such as educação, cortes, suspensão, dinheiro [education, cuts, suspension, money], related to articles on the measure per se and on what was announced by the government. On the other hand, Folha Online attributed additional weight to the articles that referred to the actions of the students and the government after the announcement of the measure, by including words such as greve, protestos, manifestação and bolsa [strike, protests, manifestations and grant].

At this point, it is worth mentioning the relationship of these results with the editorial lines of each of the analyzed media. The sociologist Gisela Taschner explains that the current Folha Group was created in opposition to the main newspaper in the city, O Estado de São Paulo, representing the more conservative, traditional, and rigid rural elites (Almeida, 1993). On the Group’s website, the editorial line is described as “[…] the search for critical, non-partisan, and pluralist journalism. These characteristics, which guide the work of the professionals of the Folha Group, have been detailed since 1981 in different editorial projects.”

Taschner clarifies that the appearance of the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo –currently Grupo Estado, of which Estadão.com is a part– is linked to a political struggle, that is, it already had a predefined editorial line: “[…] the business organization was a material framework to achieve the political objective” (Taschner, 1992, apud Almeida, 1993, p. 30). In the author’s evaluation, Estadão maintained its traditional stance by uniting political conservatism and economic liberalism in its editorials. Notas e informações is one of the most emblematic columns of the medium to date. However, since the military coup of 1964, and especially after 1968, the newspaper has taken more liberal positions also in the social and political sphere” (Almeida, 1993, p. 32).

Graph 3. A comparison of percentages of keyword use in each frame function between Folha Online and Estadão.com

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

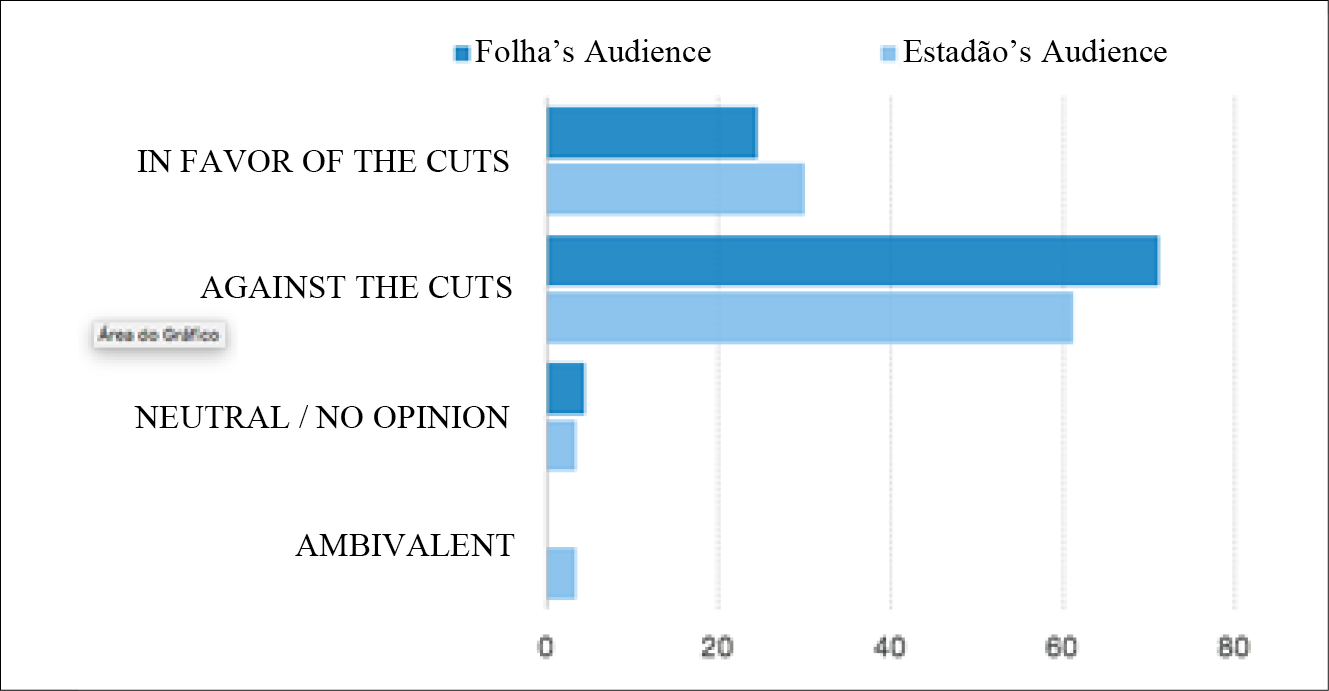

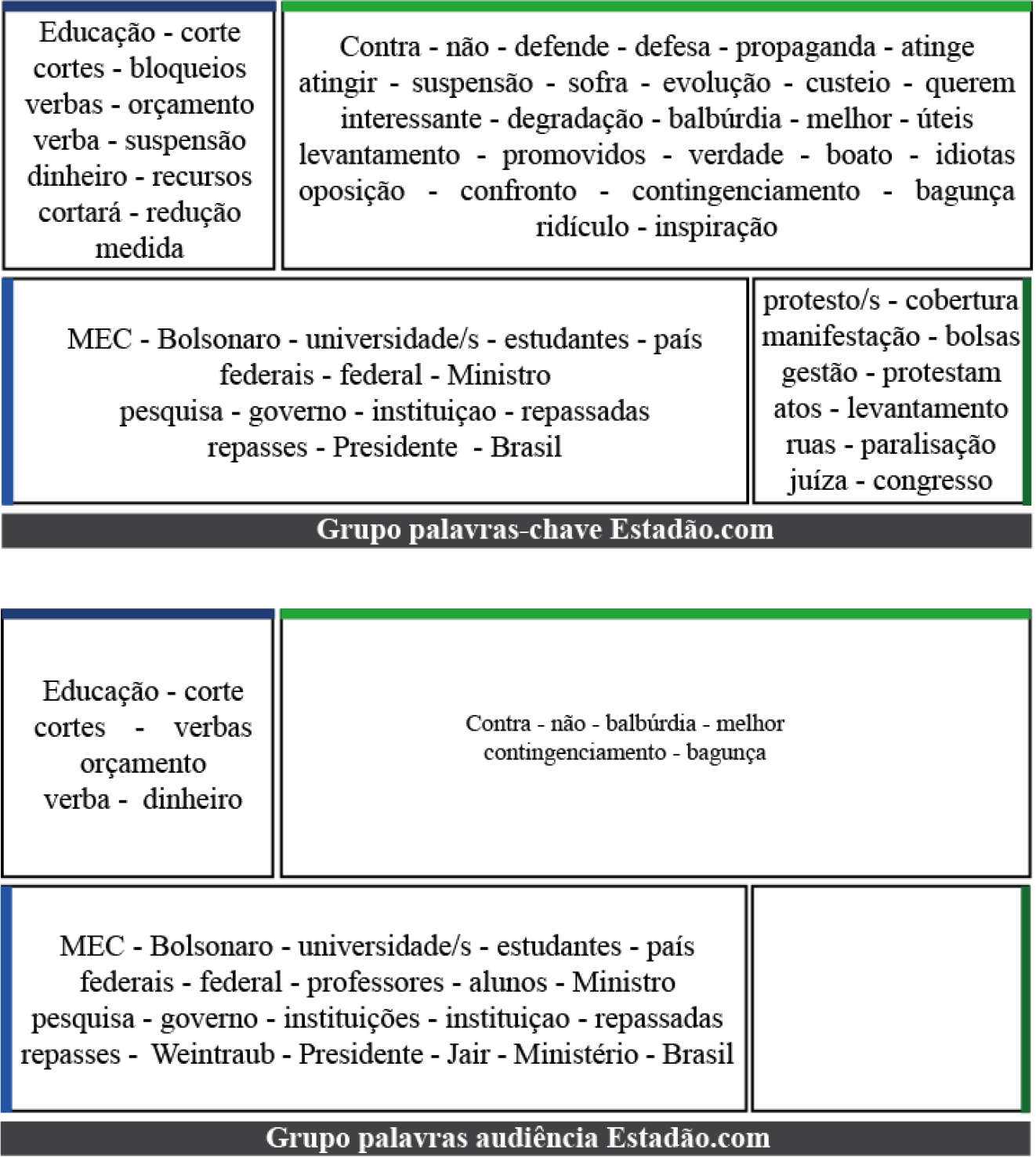

To test the relationships of media discourses with those of their audiences and determine frame acceptance –considering the environment of political polarization in Brazil– our second hypothesis predicts that the audience on Twitter would probably accept more the words related to the functions of causal interpretation (F2) and Moral evaluations (F3) presented by the media, in which Estadão.com and Folha Online had similar percentages of use.

Likewise, we anticipated that the audiences would use these words in their Twitter posts in a similar proportion, to represent their positions in a situation in which at least 95% of the collected sample had an opinion on the measure, as shown in Graph 4.

Graph 4. Trend in the comments: disapproval, approval, neutral, or ambivalent regarding the cuts of funds of federal universities

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

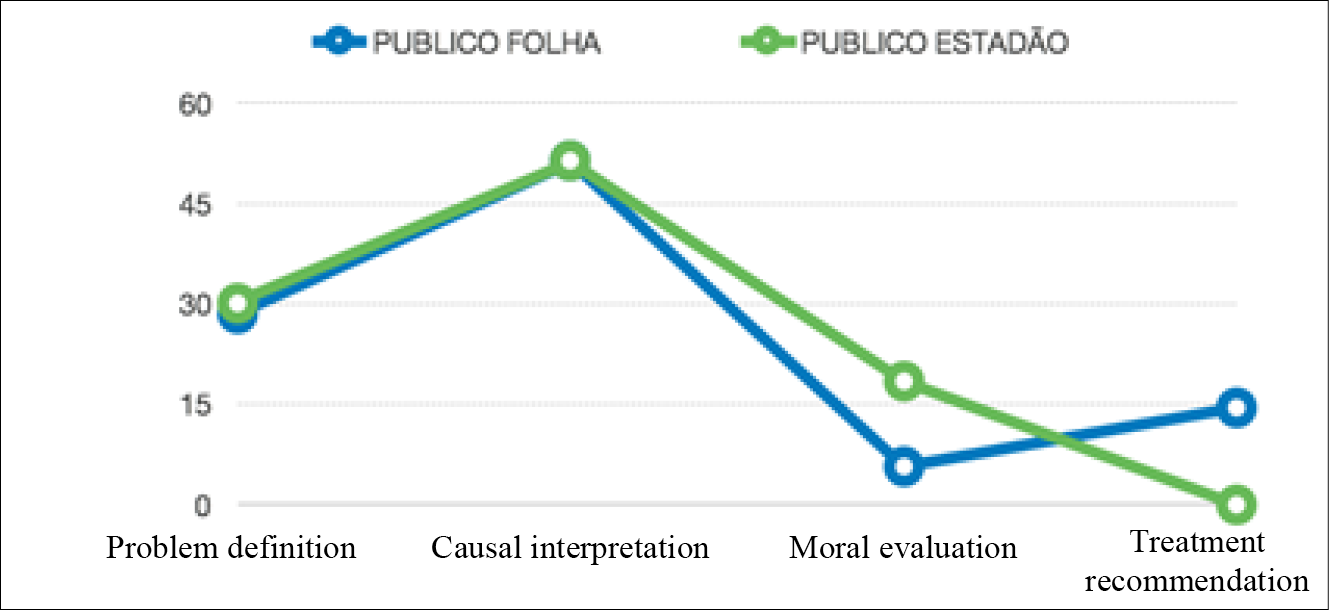

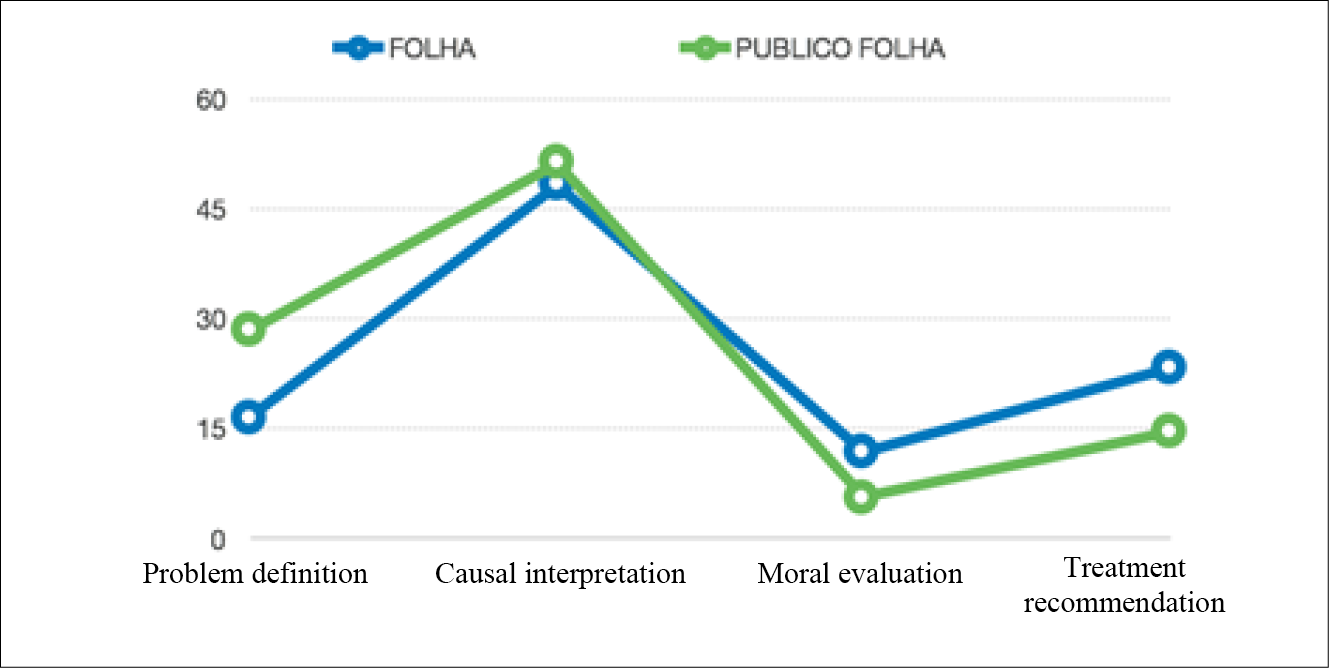

The intersection of percentages between the uses of each medium and their audiences, obtained in each of the nominal categories (frame functions), are shown in Graphs 5 and 6. In Folha Online (Graph 5), the behavior was similar. However, the use measurement shows only a significant correspondence in those words that belong to the causal interpretation: the medium used them 48.29% of the time and its audience, 51.24%. The words corresponding to the moral evaluations pointed to a distance of more than 5 percentage points between the uses of Folha Online (11.74%) and those of its public (5.69%). Furthermore, the distances in the other categories did not show a close relationship between the words used by the newspaper (F1: 16.66%; F4: 23.29%) and by its audience (F1: 28.46%; F4: 14.59%).

Graph 5. Comparison of percentages in the use of keywords between Folha Online and its audience

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

The same procedure was carried out to examine Estadão.com (Graph 6). There were meeting points in two of the four nominal categories. When defining the problem, the newspaper used a percentage of 30.70% of the words corresponding to this function. In their audience responses, this group of words was used by 30.25%.

In the categories mentioned in our second hypothesis, a relevant relationship was found between the use of words of the medium and their audience in the moral evaluation variable. The words categorized in the moral evaluation function were found in a percentage of 18.06% in the newspaper and 18.48% in its audience. On the other hand, the causal interpretations indicate a percentage of 43.51% in Estadão.com and 51.26% in its audience. Therefore, our second hypothesis was supported in the causal interpretation frame (F2) only in Folha Online and in the moral evaluation frame (F3) only in Estadão.com.

Graph 6. Comparison of keyword usage percentages between Estadão.com and its audience

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

To have an additional perspective on the relationship between the use of the identified keywords in each of the media audiences, we compared the percentages of use between the two audiences in relation to each nominal category, the results of which can be seen in the Graph 7. We found significant approximations only in the first two functions of the frames that referred to the use of keywords in the definition of the problem, which in the audience of Folha was 28.46% and in the audience of Estadão.com, 30.25%.

Graph 7. A comparison of percentages of use of keywords between the audiences of Estadão.com and Folha Online

Source: prepared by the authors (2019)

The words that mentioned or “identified the forces that created the problem” (Entman, 1993, p. 53), and corresponded to the second function of the frames, were used by the audience of Folha Online in a percentage of 51.24% and by the audience of Estadão.com in 51.26%. The almost exact match is related to the fact that audiences produce discourses that are more consistent with each other when defining the situation and identifying causal agents in it, not in moral evaluations or in the ways of addressing the problem or its possible consequences.

This is understandable in a polarized political situation in which the adoption of frames that suggest changes in the evaluations and attitudes depends on the level of engagement with the event. Therefore, and returning to Graph 3, the percentage of the audience that could be considered without or with little interest and commitment to the situation does not reach 5%. In summary, most of the people in our sample had, in their comments, some kind of position with respect to the measure, which corroborates the statement by Entman (1993, p. 55) that “[…] the power of the news can be self-reinforcing.” It is possible to infer that people found arguments in each medium that coincides with their way of interpreting the cuts in resources to federal universities. According to Ancelovici (2002, p. 434), “[…] new interpretive frames are not simply invented out of nowhere. They are based on family values, categories and symbols, and it is this familiarity that allows them to resonate with the target audience.”

In short, the acceptance of media frames by the audiences of Folha Online and Estadão.com, when taking into account the use of keywords in their publications on Twitter, showed points of agreement to define the situation. In the causal agent variables and, to a lesser extent, in moral evaluations, it was more difficult to find coincidences in the use of keywords in the opinions of the users in the tweets. A priori, we postulate that this context would benefit the adoption of frames that would mainly explain moral evaluations, but this was rejected, because, although there are points in common, the readings and perspectives of Twitter users were different, which shows the plural nature of the frames that circulate within the platform.

Therefore, this type of study cannot only be attended to from the media frames, but must also recognize the action of frames of other types of agents. In this regard, the proposal for a methodology in this article becomes important in the effort to address a workspace as dynamic as Twitter. Especially in the face of contexts impregnated with political affections.

Nonetheless, the result allowed us to identify a coincidence in the proportion of use of words according to the functions in each medium. That is, the group of words with the most repetitions in one medium was the most repeated in the other, even following different percentages. This study found no strong similarities between the two newspapers and their audiences. However, we can find relevance in the way that the discussion was addressed in the conversations of the two audiences on Twitter. In other words, the causal interpretation was the most used type of function in all the established relationships, which means that, in the initial stage of the situation analyzed, the opinion focused more on the search for those responsible for the measure.

Although the numbers do not demonstrate a correspondence between the media and the audiences, the general behavior of the moral evaluation function in relation to the others adopted in each test allows us to observe that the discussion varied. Therefore, measuring it with keywords would not allow us to find such significant relationships. Future research to assess moral issues may use, for example, the top hashtags in political controversies as variables.

As a methodological limitation and to carry out a more precise test, according to the general state of the discussion, future researches need to collect data in a period of more than two months to control the evolution of the frame adhesion by the audiences and to verify whether there were also changes of opinion, in addition to cross-checking data from other newspapers and contemplating a broader audience sample. Even so, it would be interesting to consider keywords as a central element in at least three of the functions indicated by Entman, since Twitter posts represent a methodological challenge to identify framing relationships. In fact, most Twitter search engines work from analysis units such as keywords, hashtags, or usernames, so we understand that these are the best elements to look for strong relationships in this type of research.

4. Conclusions

It is worth mentioning that our study did not consider some variables that could have changed the result, such as the location of the users and the tweets that do not use the filters in the TweetDeck tool and that still dealt with the issue. In addition, other elements in some of the tweets were not considered in the research, which could intervene in the conclusions of the study. For example, the use of gifs, memes, and photographs by the media that would complement the perspective on the subject and even give another context to certain words and posts published by the newspapers. These analysis units would also serve a specific interpretation that, as we mentioned, escaped our focus. It would be interesting to examine them in other studies on the subject to identify whether they act as frame reinforcers.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight that studies on media effects are closely linked to technological advances, so moving towards the consolidation of concepts and the delimitation of hypotheses facilitates the task of taking them to the empirical field. Precisely, when observing that framing in social networks is much more immediate, the study on the acceptance of these frames can reach new territories if the (non-journalistic) elements present in a space such as Twitter are considered. The Brazilian political arena showed similarities with other large-scale political movements, which serves to reinforce two points: (a) that the media frames adopted by an individual are directly related to the level of information and importance that that person gives to an issue and (b) that recurring frames can spread biased and often decontextualized information, contributing to political polarization and misinformation. If we accept the idea of Twitter as a space for dialogue and construction of public opinion, we admit the presence of various actors. As a reflection, we propose rethinking the mediacentric perspective of framing on Twitter, precisely because it is insufficient to encompass the influence and convergence of political actors and heterogeneous audiences.

5. Biographical references

Almeida, M. L. N. de. (1993). Folhas ao vento: análise de um conglomerado jornalístico no Brasil. RAE-Revista de Administração de Empresas, 33(4), 106-107. Recuperado de http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-75901993000400010

Ancelovici, M. (2002). Organizing against globalization: the case of ATTAC in France. Politics & Society, 30(3), 427-463.

Akhavan M. R., & Ramaprasad, J. (2000). Framing Beijing: dominant ideological influences on the american press coverage of the Fourth UN Conference on Women and the NGO Forum. International Communication Gazette, 62(1), 45-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549200062001004

Bonone, L. M. (2017). Construção de método para pesquisas de Frame Analysis. Estudos em Jornalismo e Mídia, 13(2), 78-87.

Bronstein, C. (2005). Representing the third wave: mainstream print media framing of a new feminist movement. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(4), 783-803.

Brüggemann, M. (2014). Between frame setting and frame sending: how journalists contribute to news frames. Communication Theory, 24(1), 61-82.

Callaghan, K.,& Frauke, S. (2001) Assessing the democratic debate: how the news media frame elite policy discourse, political communication, 18(2), 183-213. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846001750322970

Cappella, J. N., & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: the press and the public good. Nova York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carragee, K. M.,& Roefs, W. (2004). The neglect of power in recent framing research. Journal of Communication, 54(2), 214-233.

Chong, D.,& Druckman, J. N. (2007). A theory of framing and opinion formation in competitive elite environments. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 99-118.

Colling, L. (2001). Agenda-setting e o framing: reafirmando os efeitos limitados. Famecos, 14, 88-101.

Denzin, N. K. Lincoln, Y. S. (2006). O planejamento da pesquisa qualitativa: teorias e abordagens. Porto Alegre: Grupo A.

De Vreese, C. H. (2005). News framing: theory and typology. Information Design Journal & Document Design, 13(1), 51-62.

D’Angelo, P.,&Kuypers, J. A. (2010). Introduction: doing news framing analysis. In D’Angelo, P.,&Kuypers, J. A. (Eds.). Doing news framing analysis: empirical and theoretical perspectives (p. 1-13). Nova York: Routledge.

D’Angelo, P. 2002News framing as a multiparadigmatic research program: A response to Entman. Journal of communication, 52(4), 870-888.

Druckman, J. N. (2001). Evaluating framing effects. J. Econ. Psychol, 22, 91-101.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51-58.

Eyal, C. H.,Winter, J. P., & Degeorge, W. F. (1981). The concept of time framing in agenda-setting. In:Wilhoit, G. C. (Ed.), Mass Communication Review Yearbook: v. 2 (p. 212-217). Beverly Hills: Sage.

França, V.R.V. (2012). Discutindo o modelo praxiológico da comunicação- controvérsias e desafios da análise comunicacional. Porto Alegre: Sulina.

Gamson, W.,&Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95(1), 1-37.

Goffman, E. (2012). Os quadros da experiência social: uma perspectiva de análise. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Goffman, E. (1986). Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Northeastern University Press.

Koenig, T. (2004). On frame and framing: anti-semitism as free speech: a case study. In: Encontro Anual do IAMCR, Porto Alegre, RS.

Latinobarómetro. (2018). Informe 2018. Santiago, Chile: Corporación Latinobarómetro, 2018. Recuperado el 24 agosto, 2019, de http://www.latinobarometro.org/latdocs/INFORME_2018_LATINOBAROMETRO.pdf.

Leal, P. M. V. (2007). News frames no jornalismo político brasileiro: análise de enquadramento da cobertura do escândalo dos Sanguessugas. En: Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação, 30, Santos, SP. CD-ROM.

López Rabadán, P. (2010). Nuevas vías para el estudio del framing periodístico. La noción de estrategia de encuadre. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico, 16, 235-258. Recuperado de: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ESMP/article/view/ESMP1010110235A

McCombs M., &Reynolds, A. (2002). News influence on our pictures of the world. In Bryant, J., & Zillmann, D. (Eds.), LEA’s communication series. Media effects: Advances in theory and research (p. 1-18). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R.,Kalogeropoulos, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2019). Reuters Institute Digital News Report. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Oliveira, M. F. de. (2011). Metodologia científica: um manual para a realização de pesquisas em Administração. Catalão, GO: Universidade Federal de Goiás. Recuperado em 24 agosto, 2019, de https://adm.catalao.ufg.br/up/567/o/Manual_de_metodologia_cientifica_- Prof_Maxwell.pdf

Valera Ordaz, Lidia. Zer 21(41) : 13-31 (2016). URI. http://hdl.handle.net/10810/41231. El sesgo mediocéntrico del “framing” en España: una revisión crítica de la aplicación de la teoría del encuadre en los estudios de comunicación

Park, J. (2003). Contrasts in the coverage of Korea and Japan by US television networks: a frame analysis. International Journal for Communication Studies, 65(2), 144-164.

Porto, M. P. (1999). Interpretando o mundo da política: perspectivas teóricas no estudo da relação entre psicologia, poder e televisão. In: Encontro Anual da Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação e Pesquisa em Ciências Sociais (ANPOCS), 13, Caxambu, MG. Anais... Caxambu, MG.

Porto, M. P. (2004). Enquadramentos da mídia e política. En: Rubim, A. A. C. (Org.), Comunicação e política: conceitos e abordagens (pp. 73-104). Salvador: Edufba.

Pozobon, R.,& Schaefer, R. (2014). Perspectivas contemporâneas sobre as pesquisas de enquadramento: uma proposta de sistematização conceitual. Revista Fronteiras, 16(3), 157-168.

Rossetto, G. P. N., & Silva, A. M. (2012). Agenda-setting e framing: detalhes de uma mesma teoria? Intexto, (26), 98-114.

Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1), 103-122.

Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming and framing revisited: another look at cognitive effects of political communication. Mass Communication & Society, 3(2&3), 297-316.

Shah, D.V., Kwak, N.,& Holbert, R.L. (2001). ‘Connecting’ and ‘disconnecting’ with civic life: patterns of Internet use and the production of social capital. Political Communication, 18(2), 141-162.

Teixeira, A. V. (2017). Contribuições da análise do enquadramento noticioso para as pesquisas em comunicação. Temática, (13). Recuperado el 24 agosto, 2019, de 10.22478/ufpb.1807-8931.2017v13n5.34307.

Wolf, M., 2012. Teorias da comunicação. 6th ed. Lisboa: martins fontes, p.75.

Zhou, Y.,& Moy, P. (2007). Parsing framing processes: the interplay between online public opinion and media coverage. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 79-98.

Appendix A. Keywords that appeared at least twice in each function

Notes

1 In this article, the term framing refers to the hypothesis of media effects and will be used as the established nomenclature.

2 For greater precision, we adopt the definition given by the Royal Spanish Academy as “an expressive form that introduces representations of values and concepts in the arts, and that from the symbolist current, at the end of the 19th century, and in the poetic schools or later artistic works, uses suggestion or subliminal association of words or signs to produce conscious emotions” ROYAL SPANISH ACADEMY: Dictionary of the Spanish Language, 23rd ed., [version 23.4 online]. <https://dle.rae.es> [March 10, 2021].

3 In Agenda-Setting Theory, attribute is a generic term that encompasses the wide range of properties and indicators that characterize an object (McCombs, 2004, p. 113).

4 “Universities that, instead of seeking to improve academic performance, are making a mess of things, will have their funding reduced,” said the minister. “The university must have enough money to make a mess of things and a ridiculous event.” He gave examples of what he considers a mess: “People from the Landless Workers’ Movement on campus, naked people on campus.” First, three universities have already met these criteria and reduced transfers: the University of Brasilia (UnB), the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), and the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). Retrieved on August 26, 2019, from https://educacao.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,mec-cortara-verba-de-universidade-por-balburdia-e-ja-mira-unb-uff-e- Ufba, 70002809579

5 Source: http://www.latinobarometro.org/lat.jsp. Access: August 24. 2019.

6 We associate ourselves with Oliveira (2011, p. 27), for whom “[…] there seems to be a consensus, therefore, regarding the idea that qualitative and quantitative approaches should be seen as complementary, instead of competing with each other.”

7 TweetDeck is a software that allows you to publish, monitor, and manage profiles on Twitter.

8 Retrieved on August 24, 2019 from http://www.contadordepalavras.com/

9 “Frames exert their power through the selective description or omission of characteristics of a situation” (Entman, 1993, p. 56).

10 In Portuguese, the word “balbúrdia” references disorder, lack of productivity or optimal utilization of public resources. The term with which the Minister of Education addressed the activity inside the federal universities.

11 At this point in the study, we considered frames the keywords which were attributed to the framing function suggested by Entman.

doxa.comunicación | nº 32, pp. 405-430 | January-June of 2021

ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978