1. Introduction

Teaching creativity in Advertising and Public Relations undergraduate degrees is a subject of study in the university community. On the one hand, the current professional advertising environment requires more specific digital competencies from graduates (Álvarez-Flores, et al., 2018) and creative and strategic abilities (Altarriba & Rom, 2008). On the other hand, lecturers have often been found to have had little contact with creativity in the professional environment (Farfán Montero & Corredor Lanas, 2011), or they do not have any training in pedagogy and tend to embrace traditional teaching practices (Morales Bueno & Landa Fitzgerald, 2004, pág. 146).

In this context, “the need to address the lines of research and action to improve the creative advertising market situation linked to university teaching” (Llorente Barroso et al., 2021: 112) arises. Although research shows that lecturers are unlikely to change teaching-learning methodologies from one course to the next since it is a slow and demanding process (Sanz-Marcos et al., 2021), the innovation proposals in higher education in the area of creativity in advertising show that the professional sector’s experiences with graduates have been adequate and satisfactory. (Llorente Barroso, et al., 2013).

Teaching innovation uses inductive methodologies with which “the student learns while facing specific problem situations in specific contexts and from these experiences the knowledge is induced by applying it in other circumstances” (Navarro Asencio et al. 2017: 194). Among these methodologies, we find problem-based learning (PBL), which challenges the students to work on a problem during a period. Next, they need to research, discuss, choose, reflect, correct and defend their proposals. This approach makes the students participants in the lesson- they are not mere receivers of information-thus taking responsibility for their own learning (Giné Freixes, 2009). This dynamic is experimental, which the creative environment requires. In these cases, the lecturer’s primary function is to design the learning experience through strategies and techniques that facilitate the student’s understanding and personal development (Gargallo López et al., 2007).

Most of the didactic innovation proposals in university education focus on the use of digital technology (Elías Zambrano et al., 2021). It has become even more significant due to the situation brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, acquiring creative skills is not only limited to digitised creative tools but can also be achieved through traditional channels (Sanz-Marcos et al., 2021). In this sense, educational experiences based on storytelling reveal its strength as it can be used as a didactic tool and creative stimulus (Roig Telo et al., 2021), and teaching innovation in advertising using methodologies oriented to problem-based learning have proven their viability (Llorente Barroso et al., 2013). In this context, it is hypothesised that classical disciplines such as narrative, focused on analysing and creating stories and their multiple discourses, offer techniques and helpful didactic resources: the objective is to integrate them into a teaching programme to learn the creative advertising process using a PBL model.

Narrative thinking is complementary to creative thinking, as it provides ways of organising information, is responsible for creating plausible and symbolic realities, cognitively structures thought, and gives meaning to our life experience; it is an innate ability adaptable to any media and the foundation of educommunication (Bermejo-Berrós, 2021; Roig Telo et al., 2021). Narration is an established tool in the advertising area and is persuasive, functional, memorable, emotional, experiential and didactic (Jiménez Gómez, 2013; García López & Simancas González, 2018). The question is, how do we create a story? Moreover, how can a story connect with advertising interests? And how can we teach how to create advertising narratives? Integrating storytelling as a didactic tool in the training programme for creatives presents an opportunity to improve the quality of university education, and this research aims to prove this.

2. Research methodology

The research uses an applied innovative teaching approach that aims to resolve problems in an educational context. One of the typologies of applied innovative research is action research, which

“is what the lecturers do themselves to analyse their performance in the classroom and incorporate changes to improve (…), The lecturer designs innovation in the classroom and at the same time asks whether this innovation produces the expected results and proposes an investigation to answer this question” (Navarro Asencio et al., 2017: 43-44).

The action research procedure is adapted to this research’s general objective: to rethink teaching-learning practice in the creative advertising subjects in higher education. Therefore, the methodology guides the research process to design a teaching methodology and implement it practically. The guidelines of this research are the following:

2.1. Situation analysis

The basic situation of a creative advertising subject from the Advertising and Public Relations degree was studied. The strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) of the teaching experience from the 2017-2018 academic year were analysed. The need to develop a didactic proposal arose, which solved the teaching-learning process’ deficiencies and improved its opportunities.

2.2. Designing a didactic proposal

A teaching proposal was designed to help the students understand the creative process in advertising and foster their creative abilities. This methodological proposal is based on PBL models and integrates narrative techniques to convey students’ creativity. The teaching programme design is detailed in the following sections, which this research’s authors created. It preceded the implementation of the methodology in the classroom. A documentary and literature review have been used to design this methodology. We have also analysed its didactic viability.

2.3. Implementing and evaluating the teaching proposal

Once the teaching methodology had been designed, it was implemented during the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 academic years in the same subject that was audited the previous academic year. We gathered qualitative information through a tutorial diary, observation, the lecturer’s experience as a witness, and the participants’ self-evaluation of the student work groups to evaluate how innovation in the classroom functioned. Quantitive data was gathered through the grades and lecturer satisfaction survey results. This data will allow us to test the methodology designed and find ways to improve it.

The teaching innovation’s methodological development is explained below, and the results are obtained from its implementation.

3. Methodological development of a teaching innovation for the creative area in advertising

3.1. Situation analysis and specific objectives

Opportunities for improving teaching were detected in a SWOT analysis of the teaching experience from the 2017-2018 academic year, in which traditional teaching methods were used. This analysis reflects the master class as a threat- aimed at teaching and transmitting structured knowledge (Gargallo López et al., 2007)- hinders the students from gaining insights. Students are also doubtful of their own creative abilities, or, as Elena González Leonardo informs (et al., 2020), they do not know what makes something creative. These reasons motivated the need to reformulate the methodology used in the subject of Advertising Creativity since students must recognise and evaluate the creative and carry out a complete creative process to exercise their profession. Therefore, we proposed to design teaching innovation to teach creativity in advertising at university following some specific objectives:

- SO1) To simulate a real working environment in the classroom for the student to experience the different stages in an advertising production process.

- SO2) To design a teaching-learning method that prioritises practical collaborative exercises and achieving an objective.

- SO3) To bring the students closer to accessible techniques and tools to create with which to create, plan and provide solutions to real projects and cases.

- SO4) To make the students aware of their own creative and strategic abilities.

- SO5) To make the students responsible for their work, decision-making, and learning.

3.2. Design of the didactic proposal

We have designed a teaching programme using the PBL methodology, which integrates knowledge from two disciplines: creativity and narrative. Unifying these disciplines is novel since narrative techniques are used as a creative tool and applied to the didactic and advertising process. If creative thinking is activated to solve a problem in a novel and helpful way (Pacheco Urbina, 2003) narrative thinking is activated to understand and respond to the environment (Bermejo-Berrós, 2021) to construct a symbolic and plausible reality around it. Both disciplines are adapted to a methodological framework and aim to spark new ideas and allow students to approach resources and implement them in an organised, coherent and understandable way. Both disciplines are adapted to the teaching guide, and it is based on the phases of the creative process in advertising (Hernández Martínez, 2012; Berzback, 2019), in which the student experiment the roles from the professional environment and their main functions in the classroom (table 1)

Table 1. Phases of the advertising creative process

|

The creative process |

The creative process in advertising |

|

|

Phase 1 |

Preparation |

Receive advertising briefing and evaluation of the problem. |

|

Phase 2 |

Incubation |

Advertising research, analysis, and strategic planning: definition of the objectives. |

|

Phase 3 |

Illumination |

Design of the creative idea: definition of the essence of the message to be transmitted, etc. |

|

Phase 4 |

Production |

Development of the campaign, elaboration of the advertising messages, etc. |

|

Phase 5 |

Verification |

Evaluation of the campaign, presentation, and sales, etc. |

Source: created by the authors

The initial premise of PBL is that the student creates an advertising campaign during the fourth-month period. They must complete the different phases of the creative process with the lecturers help, which will determine their final work. In this dynamic, the lecturers advise the students instead of transmitting information, “they become consultants to the students” (Morales Bueno & Landa Fitzgerald, 2004, p. 148)

The phases of this teaching methodology for subjects in creativity in advertising at the university level are set out below.

3.2.1. Phase 1. Preparation: the brief

An advertising project begins by receiving a briefing from the advertising agency. It outlines the advertising company’s commercial or communicative needs. It contains essential information about the company or the product and the objectives for the situation or problem (Muela Molina, 2018). The agency evaluates the brief and, if necessary, writes a counter briefing 1. The case is assessed in this advertising pre-production phase linked to the account department. The didactic case begins by asking the students to prepare this document; to complete this task, they must choose a brand or advertiser in a situation of change or crisis. It is carried out in groups, and each group works on its brief throughout the term. It is essential that the team detect a communication problem and set out specific objectives as a starting point for the advertising campaign since a part of the final evaluation will depend on this. The lecturer can also approach this phase by briefing each team to prepare a counter briefing of the case they will work on during the four months.

3.2.2. Phase 2. Incubation: the strategic planning of the advertising project

In this phase, the students take on the role of planner, whose function and professional responsibility is to apply research to approximate the brand experience to the consumers’ expectations (García Guardia, 2009).

The advertising strategy needs to be detected and defined: the consumer’s insights, the strategic advertising concept, and the media consumption trends. We draw up a plan with this data to reach the advertising campaign’s objectives resulting from the research; they must be outlined in a document that some authors call creative brief.

The teaching staff must show the students the external sources of information and how to devise their own research methods for planning the advertising project. The following are the goals to be achieved by the students in this phase.

a) Consumer profile analysis

The psychological term insight is used in the advertising industry to connect emotionally with users instead of generating messages with rational, persuasive arguments (Ayestarán Crespo et al., 2012). An advertising insight is the consumer’s insignia, a characteristic feature that defines them. An advertising story captures people’s interests through allusions since they will relate to the content of the message (De Miguel Zamora & Toledano Cuervas-Mons, 2018; Castelló-Martínez, 2018). However, it is not easy to detect this project’s main aim. Planning the advertising process is based on insight, but planning also requires a social-storytelling narrative or creative idea through which all the campaign messages will be elaborated.

Lecturers have ethnographic and social research tools to guide the students to detect the insight (Castelló-Martínez, 2019). These include interviews, questionnaires, discussion groups, observation of the case as an active participant, persona method, or empathy maps. The last two techniques are recommended in the classroom due to their accessibility.

Empathy maps and the persona method (Gasca & Zaragozá, 2019) are tools that help to define a user’s profile, and they follow the guidelines of persona design. In other words, this exercise is devised for the student to design a character with the target audience’s qualities to understand them intimately by internalising their needs projectively. It collects the same consumer data as those needed to create a character in a novel (Páez, 2010: 158-159): what they do, what they think, what they say, how they speak, what they think of other characters and their peculiarities.

Once the type of ideal consumer has been researched, their profile is concluded by defining the target –sociodemographic variables– and their personality traits or characteristics –insights–. It is essential to detect the character’s personality, frustrations, and motivations since this is the source of the conflicts that give rise to an advertising narrative. The insight must possess a unique and conflicting feature to tell a story; they must project a motivation to nurture or frustration to overcome. Focusing the advertising strategy on detecting this means integrating narrative techniques into the creative process from the start and creating the main character of a story that the consumer can relate to.

b) Corporate profile analysis

The corporate profile is the differential feature that defines the brand (Castelló-Martínez, 2018), a concept that the consumer associates with the brand. It expresses what the brand wants to communicate and is a symbolic element that the brand takes on so that the ideal user will identify with it. Therefore it should be complementary to the insight.

To find the concept, we must define a value- or character- to enhance the insight’s motivations or mitigate their frustrations, depending on how it is previously described. It is about finding a Sancho for a Quixote.

The concept provides insight into the ideal strategic conjunction to create advertising messages from narrative techniques. They complement each other to create a psychological narrative that leads to persuasive action. The value proposition tool of the canvas model is useful (Design Thinking Spain, 2019b) to define the corporate profile linked to the target audience’s profile. With this technique, the student establishes the symbolic and affective ties a brand should have with its ideal user.

The brand concept materialises in the form of a word or short phase, offers a focus to the advertising message, narrows its content, and specifies the positioning with which the brand wants to present itself to the public. It must be concise, symbolic, or denotative of an emotional or rational benefit to the insight (De Miguel Zamora & Toledano Cuervas-Mons, 2018).

c) Media profile analysis

The analysis of media creation and consumption trends is important strategic data. The decision to broadcast the message on one platform or another must be deliberate and agreed upon by the work group according to the interests of the insight and the brand, hence the need for this study. Lecturers should guide students towards managing and finding external sources of information: indexes, trend studies, or audience analyses.

3.2.3. Phase 3. Illumination: the creative idea

The student already takes on the role of the creative, whose responsibility is to generate original ideas that provide solutions to the initial brief. In this phase, the previously defined strategic variables are unified in what is called: creative idea. This is the core of the communication campaign, a hypothesis that gathers the essence of the advertising promise. The creative idea encompasses the new perception, positioning, or dynamic that the brand wants to establish in the social context and the consumer’s mind. It promotes a change of attitude, hence its narrative conception, since all narrative text is a structure of ordered elements with an evolutionary nature, and its function is transformation. The change from one situation to another is the basis of every story and, therefore, the advertising narrative seeks to change the consumer’s mind (Escribano Hernández, 2018).

The assumption that the creative idea is a narrative makes it a functional tool. The creative advertising idea is a narrative that shapes a new reality, attitude, or belief. As an idea, it is intangible, it mentally captures what the brand wants to be or communicate, and it materialises through messages in different media. The idea at first is initially mental or symbolic- referential- and requires techniques for its landing or sensory perception.

In this phase, the student faces the development of the idea from an imaginary perspective to sensitise it in the later phases. The strategy for disseminating the ideal is also outlined. The goals to be achieved by the students in this phase are detailed below.

a) The architecture of the advertising narrative

The Lecturer has basic narrative strategies that provide didactic and operative structure to the ideas: the actantial narrative model by A.J Greimas (1976), which presents a methodological framework for the analysis and creation of narrative messages and the understanding of factors involved in them (Pineda, 2018).

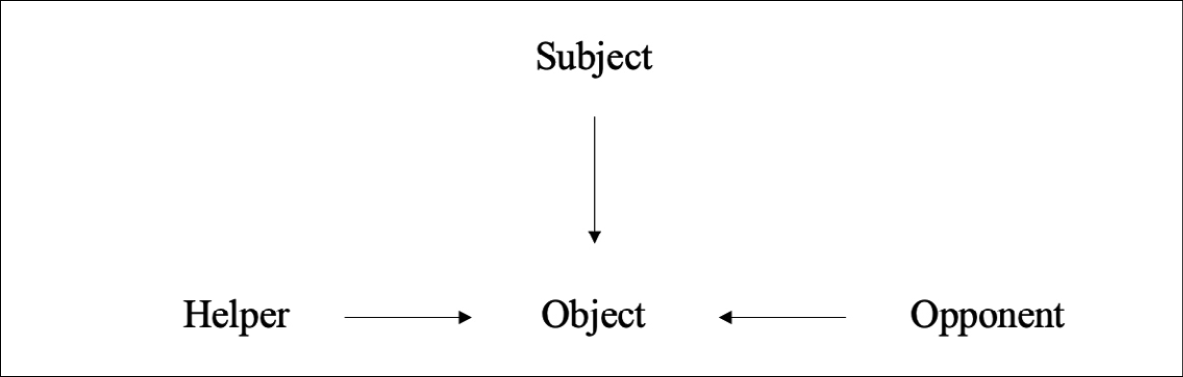

The actantial model posits a subject’s conflict whose object of desire is surrounded by a helper or an opponent (Pineda, 2018). This structure facilitates the shaping of an argument or advertising microstory that integrates the previously detected variables: insight and the concept. Figure 1 provides the architecture that takes the creative idea into a narrative, supporting the brand’s argument and favoring the insight.

Figure 1. Actantial advertising model

Source: created by the authors based on the reformulation of A.J. Greimas’ actantial model

The students’ mission is to create a micro-story or advertising narrative using this model and the strategic variables specified in table 2. The subject, object, and the opponent are related to the consumer profile. At the same time, the helper is related to the corporate profile, i.e., the brand is to be remembered by the helper, which is the concept. The content of the message is based on this model, which offers a dynamic of working for the project and a social narrative that must be made tangible in the subsequent phase by elaborating of messages adapted to a specific format and means of dissemination.

Table 2. Strategic values acquired by the actantial advertising model

|

Actantial variable |

Strategic value |

|

Subject |

Target demographic. |

|

Object |

The element that motivates the subject’s action is extracted from the insight. It is a desire, need, or expectation. |

|

Opponent |

The element that frustrates the subject from gaining their object of desire. It is also extracted from insight. It is frustrating or an impediment to achieving their desires or needs. The receiver of the message has a satisfactory experience by overcoming the narrative action of the message. |

|

Helper |

The advertising concept –associated with the brand– is represented as the helper of the subject aimed at achieving their desire. Thus, the brand gains a positioning in the consumer’s mind. |

Source: created by the authors

b) Dissemination map of the advertising narrative

Once the content of the advertising narrative has been defined, the student must decide the medium on which it will materialise. To do so, they rely on the media consumption trends investigated in the strategic phase and studies on how to integrate the advertising narrative in the media related to the insight, in other words, in those media territories where the potential user usually interacts (De Miguel Zamora & Toledano Cuervas-Mons, 2018). The solution involves finding advertising spaces in which to tell the story. In this way, the creative idea takes on a tactical functionality and can be managed more operationally.

As a teaching tool, it is useful to use mind maps to teach how to plan the ideal means of disseminating a campaign. A mind map, for example, whose epicentre is the insight provides algorithms of the potential user’s consumption and media behaviour and, therefore, facilitates decision-making regarding the channels for disseminating messages. Designing a mind map is to strategise with the creative idea to optimise the reach of the messages and the interaction with the campaign.

3.2.4. Phase 4. Production: design of the advertising message

The student creates, specifically writing and graphic design functions, under an aesthetic coherence and a tone appropriate to the campaign objectives. This is a landing phase where the creative idea is given tangible form. The advertising narrative must be reflected in the different types of messages.

The lecturer can guide this practice using scripts, step outlines, storyboards, mood boards, sketches, etc., to support the design process according to the format of each item. It is a practical phase for the student and a guided work by the lecturer. A constant dialogue is established between both the student and the lecturer, like in any professional creative team, to establish the aesthetic lines for the campaign and its final integration in each format.

The design and the discussion of the suitability of the message is the student’s responsibility in this phase. To dynamise the generation of ideas and decision-making, the SCAMPER method can support this practice, which allows for exploring creative ways about something that already exists (Design Thinking Spain, 2019a). It is executed by formulating: substitutions, combinations, adaptations, modifications, proposing other uses, eliminating or reorganising elements of the message.

3.2.5. Phase 5. Verification: evaluation and defence of the project

In the professional environment, the presentation of the campaign is made to the client or advertiser who has commissioned the advertising services, and it is the last stage of selling and defending the project. Therefore, it is essential to outline the arguments that support the campaign’s effectiveness according to the initial objectives and to generate expectations. This work is eminently persuasive, and its approach is based on narrative formulas for elaborating the discourse. Each work group will defend their project before a lecturer and classmates as a didactic exercise.

The speech requires organisation, planning, and order. Connecting the ideas and conveying them persuasively means establishing a link with the interlocutor, grabbing and maintaining the receiver’s attention during the speech.

The story’s classic structures are used to elaborate this discourse: beginning, middle, and end. Screenwriters and narratologists add turning points to this basic structure to captivate the receiver’s attention (Field, 1995; Páez, 2010). Rajas (2014) explains that three strategies are used to manage the focus of the delivery of a speech: intrigue, surprise, and suspense, whose application to the advertising message produces persuasive effects.

Intrigue is a mode of delivery used as a hook since the receiver will try to find out how the speech continues, which keeps them attentive. Surprise allows the receiver and emitter to relate to each other and is part of the speech in which arguments are presented. Suspense provokes tension in the receiver since they anticipate the solution to the initial conflict. In general terms, the basic speech in three acts should be governed firstly by uncertainty or intrigue, secondly by surprise, and thirdly by suspense2 (Rajas, 2014). Presenting the project with an oral speech based on this structure makes the defence dynamic and convincing.

3.3. Programming the teaching project and the didactic viability analysis

Integrating the creative advertising process into the teaching programme is feasible due to its timeline and the competencies under a project-based learning methodology. The proposed design aims to make lessons an exercise of practical internalisation for the student, as a professional simulation, based on the lecturer’s tutoring with work techniques and support in theoretical materials.

The approach of this programme is that the creative process itself shapes the learning process, in phases in which techniques and procedures are proposed to promote the students’ creative abilities (López-Fernández & Llamas-Salguero, 2016).

The starting point is a practical case: designing and implementing an advertising campaign. This work is carried out in small groups of students (3 or 4 members), and based on this initial assignment, the route to be followed by the student during the four months is drawn up3 (table 3).

Table 3. Timing of the course in action phases

|

Area |

Timing |

|

|

Phase 0 |

Presentation of the subject. |

Week 1 |

|

Phase 1 |

Elaboration of the briefing and/or counter briefing. Detection of the problem and definition of the project’s starting point, etc. |

Week 3 |

|

Phase 2 |

Contact with the challenge. |

Week 5 |

|

Phase 3 |

Design and architecture of the creative idea. |

Week 8 |

|

Phase 4 |

Development of the campaign. |

Week 11 |

|

Phase 5 |

Evaluation of the designed campaign. |

Week 14 |

Source: created by the authors

The first sessions of each phase were dedicated to contextualising the task to be performed and the specific objective: the theoretical framework is introduced, the associated supporting documentation is given, and example advertising cases are analysed. Master class and case study methodologies are used for this purpose.

In the intermediate sessions of each phase, students worked in groups on their projects using tools and techniques offered by the lecturer in class. They are dynamic sessions in the form of a workshop in which the lecturer demonstrates the use of a technique and the students put it into practice to develop their project. They explore and discuss this technique’s possibilities in their creations and make decisions.

The final sessions of each phase involve an evolution, and therefore, the objectives must be achieved to move on to the next milestone. In these sessions, tutoring dynamics check that the goals have been completed. The lecturer requires, at this point, a tutoring diary in which they collect the follow-up of the guided work in the classroom itself, achieving objectives and/or reorienting results if necessary.

For the project’s final evaluation, a rubric is used with items for each phase of the project. However, the final results of the work are quantified. There is also a marking percentage related to monitoring the continuous assessment that the lecturer has gathered in their tutoring diary.

4. Results of the implementation of the teaching innovation

The methodology designed arose from the audit and reflecting on the teaching experience in the 2017-2018 academic year and was implemented in the same subject in the following years. Thus, we have been able to test its functioning and verify its flaws. During the 2018-2019 academic year, there were 17 work groups in the classroom, and during the 2019-2020 academic year, there were 20. In total, we have the results from 37 groups of students who have worked using this methodology. Below are the evaluation results in each of the phases of action according to the lecturer’s tutoring diary data record and from the conversations held with the groups of students after asking them for their self-evaluation at the end of the fourth month period.

4.1. Phase 1 evaluation

In an introductory phase in which the groups worked autonomously, their task was to research the media and consumer news, searching for an entity or brand with reputation, sales, or credibility problems. With this information, they must draw up an advertising brief that includes the detailed crisis and the specific objectives that they would like to achieve.

Each group presented its report, and both the lecturer and classmates intervened with questions, initiatives to broaden the scope, or requests for rectification. All the proposals were about real current cases, which fulfilled the exercise’s statement requirements and offered a dimension close to reality. Only 8% of the groups had to rectify the content and propose new objectives to move on to the next milestone.

Skills such as predicting changes in the environment, detecting problems, analyzing, and formulating objectives are practiced in this phase. All of them are associated with the personality traits of a creative.

4.2. Phase 2 evaluation

The detection of insights was the most challenging part of the project for all the groups. The difficulty stems from the definition of the term and how to detect them since it is not a tangible element that makes it difficult to use. Insights are often detected through intuition, but this is not a didactic argument. Therefore the use of narrative character design techniques through empathy maps and the persona method were the tools chosen for working on the target audience profile in the classroom. It has been proven that the research of insights through empathy maps allows for introspection. However, it turned out to be confusing and unreliable for students. They did not trust that the audience profile could be valid because they had made them up.

A hundred percent of the groups doubted the results obtained with this technique. They had to rely on the lecturer’s guidelines and move forward in the project to realise that they were actually working on a solid foundation. The feedback shows that only 13% had poorly detected the ideal consumer’s profile.

Something similar occurred with the definition of the corporate profile. As an identity in the proposed methodology, the brands are defined through a concept that, as another intangible element, adds complexity to the strategic advertising model presented in the didactic model. In this section, the students centre on defining qualities of the product as it was a tangible element, which is erroneous when seeking to communicate persuasively in a narrative and, therefore, emotional nature. The value proposition technique of the canvas model to link the user profile helped aid students in detecting the concept associated with the brand. This technique materialises both the public’s needs and the brand’s, allowing them to establish links between them to create synergy arguments. The students understood this tool better and its functionality and worked autonomously. Despite this, 16% of the groups could not define the concept optimally according to the feedback obtained.

The analysis of media trends was the less problematic objective in this project phase. Only 1% of the groups forgot to include it as a strategic variable. This phase allows for acquiring the competencies such as the ability to analyse the social environment and planning and managing information.

4.3. Phase 3 evaluation

The architecture of the creative idea was a more straightforward exercise for the students than the previous phase of the investigation, which indicates that the formula and the process designed worked coherently. The most complex part of the advertising process is finding the entire campaign’s idea. According to the strategic variables, planning that idea enabled the students to pass this thinking of an idea phase satisfactorily and without complications. Around 14% of the groups had shortcomings in this milestone, but it coincides in all cases with the groups that had defined their insight and/or concept inadequately.

The effective resolution of this phase shows that conceptualising the creative advertising idea through narration makes it operative instantly. In conjunction with the advertising strategy, the narrative strategy is a successful didactic tool and a valid formula for creation.

The exercises in this phase allow for working on competencies such as synthesizing, concretizing ideas, order and defend arguments, and finding new ways of interpreting reality.

4.4. Evaluation phase 4

This phase is considered a new start because it is a turning point in the project. It has been confirmed that the work groups needed a break to assimilate what they had developed and what needed to be done. Some groups, around 10%, thought that this break was a setback and even experienced the need to reelaborate the creation they had already designed. They evaluated the situation with the lecturer, and it was the students themselves, under their responsibility and agreed on decisions, who decided how to go on. Only two groups rectified the idea in the previous phase, which did not lead to them losing marks since the students realised that they could learn from their mistakes.

This phase is very dense and technical. Until the previous stage, the process was mental, but they did not need technical knowledge from that moment on with which to elaborate the final advertising messages. In this sense, the Creative Advertising subject gathers students’ abilities which they had previously acquired either in parallel in subjects such as graphic design, art direction, audiovisual language, or copywriting. Basic notions of these subjects were introduced into the classroom to guide the work process.

The integration of the creative idea in the different media formats required sketching and scripting techniques to visually and textually capture the matrix narrative on a specific canvas. The first sketches and scripts were debated with the lecturer until receiving improved versions in the final items.

The SCAMPER model was used by a few groups, around 21%, since the narrative itself sparked innate patterns for expanding their own creation in different media. This shows that the mind maintains a narrative discourse that facilitates creative work. Therefore, once the student knows that they have to communicate, it is easy to explore how they will present it in the media. The general doubt that arose at this point was not to decide on what option of the various proposals designed conveyed the idea the best. In these cases, the tutorials with the lecturers were directed at evaluating the creativity of each of the elaborations and studying what adapted better to the brief’s initial objectives. This casuistry occurred in 25% of the groups, and the students always made the final choice after discussion. In this way, the responsibility for the project always belonged to the students.

The students acquired competencies in art direction, copywriting, decision-making power, and teamwork. Skills that are also required for developing digital competencies.

4.5. Evaluation phase 5

The presentation and defence phase of the projects was not problematic. It is a dynamic which students are used to. However, the guidelines such as how to structure the speech in acts and expectations enabled 10% of the groups to make dynamic presentations in which the audience could participate actively, which meant that the audience paid more attention. In the staging, the student demonstrates their verbal and non-verbal communication skills, their ability to react to questions from an audience, synthesise, improvise, and respond to the interlocutor’s questions.

4.6. Global evaluation

The students were asked to gather in groups of 4. Groups of 5 people were allowed in exceptional circumstances to prevent students from working individually. However, it has been demonstrated that groups with five students do not work well. In these cases, the students lost the global perspective by ceding responsibilities and sharing different parts of the project. In contrast, they collaborated equally among all the group members in the smaller work groups. It has been confirmed that the ideal situation is that they are composed of 3 members so that there is a balanced workflow and to experience the professional roles of planner, creative writer, and art director.

The timeline of the programming phases required changes because phase 3 was assimilated easily by the students, and it was reorganised so that another week was given to phase 4, which the students appreciated.

The lecturer satisfaction survey results, particularly the questions regarding the following and learning of the subject, show a higher rating in the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 surveys, when this methodology was implemented, than in the previous course, when the sessions had a traditional approach.

All the techniques used in the methodology are free accessible, versatile, and adaptable tools for online and face-to-face teaching modalities.

5. Discussion

5.1. The lecturer’ perspective

Implementing teaching innovation in the classroom has brought about a change in the role and thought of the teaching staff, as the PBL studies advise (Gargallo López et al., 2007). Lecturers have become consultants in the classrooms and, on occasions, the student’s workmate. This requires a change in attitude in class and, in particular, practical preparation and mastery of the material –not only theoretical knowledge– to carry out the exercises with the students and/or guide them in practice.

“The lecturer’s role is fundamental since this is the person who stimulates and compensates the student’s creative talent. The lecturer’s original and creative spirit should prevail at all times, which promotes the incentive to create, invent, imagine and ask” (Pacheco Urbina, 2003: 24).

In this context, the lecturer knows the creative processes and should learn how to teach them and strengthen them. This experience confirms that lecturers in the area of creativity in advertising should have both research skills and professional experience. When these skills are balanced, the possibility of providing training that meets the requirements of the professional sector is maximised.

The PBL has needed other methodologies from a didactic perspective during the term. There have been masterclasses to show the themes of the contents relative to each phase of the project. We have employed learning by doing, focused on students putting the acquired knowledge into practice. It has been useful for reaching objectives in each phase of the project, as previous investigations showed (Llorente Barroso et al., 2013). There have also been reactive and proactive tutorials in small groups (Fidalgo, 2011) and flipped classes when the work groups presented their problems to classmates to seek new contributions and/or resolve their doubts, fostering collaborative learning (Andrade & Chacón, 2018). Adopting and combining these methodologies- which were not all initially proposed in the programming- has also been developed intuitively by the teaching staff as the sessions progressed, requiring investigation and extra time for the organisation. Training in pedagogy for the university teaching staff has been necessary for the day-to-day running and for implementing innovations.

It has been demonstrated that using classical disciplines to design learning models is feasible regarding the didactic model. Moreover, it is easy to implement in the classroom; both face-to-face and online It covers traditional competencies and digital ones since ideas are digitized in the message elaboration phase on different electronic devices. Moreover, both types of skills are those requested in the professional sector (Moreno Solanas, 2017; Perlado Lamo de Espinosa & Rubio Romero, 2017; Álvarez-Flores, et al., 2018).

Regarding the evaluation, we chose a system of evaluation by rubric. The final project results and the following up of the work were evaluated throughout the term; this activity was registered in the lecturer’s tutoring diary. Another option would have been to assess the practice of each stage of the project, which was considered to entail an overload of time correcting that was not operative for lecturers, as Giné Freixes (2009) warns, and it was ruled out.

The methodological design of teaching innovation has been an uphill task. It has required theoretical and documentation research in pedagogy and the techniques and procedures associated with literary creation to adapt them ingeniously to the process of advertising creation and try them out in the classroom. As Sanz-Marcos (et al., 2021) mentioned, teaching methodology innovations are scarce since it requires effort and dedication that must be combined with the daily running of the university and can increase the lecturers stress and generate burnout (Moreno Jiménez et al., 2009). This is an issue for the quality of teaching and the university’s credibility as an educational institution since methodological innovations are solely the lecturer’s responsibility, which has hardly any funding and requires them to do work activities in their personal time.

Despite all the extra effort made, this project has also been a learning experience for the teaching team, the motivating agent, and the creative personality of the lecturers, who train on their own, which should also be valued.

5.2. The students’ perspective

According to the conversations with the students at the end of the course, the experience they had was somewhat motivating. They evaluated the class dynamics as “different,” the lecturers’ way of working as “friendly,” they had the sensation of professionalism and that the lecturer was invested in their learning. In these conversations, very few negative aspects were identified. Nevertheless, cases of frustration were registered in the tutoring diary by a small number of students who did not understand the inductive work dynamic or the teaching model. This is common due to the students’ role as active agents of the learning process (Gargallo López et al., 2007), but it is an indicator that a change of thought is being promoted (Pacheco Urbina, 2003). These cases usually coincide with more rational students, and thanks to group work, they found a way to respond to the project’s needs and adapt to the pace of the class.

When finalising the project, some students asked with interest whether this methodology is used in advertising agencies, which gives rise to other lines of research since despite proposing it as a didactic model, it could be tested as a strategic creative model in a professional environment.

Students worked actively in class, with enough time to exercise their creative abilities through simple creative techniques applied to advertising. It turned out to “be fun” for most. This shows that storytelling is attractive for students. It has turned out to be an understandable tool, easy to manage, which sparked students’ imagination and fostered technical skills, similar conclusions to those found in the experiment designed by Roig Telo (et al., 2021). Few cases of frustration or disappointment were detected, and a minority felt that the practical activities were “useless,” which is attributed to the lack of habit of flipped classes in which the effort falls on the student and to the lack of familiarity with the active dynamics in the classroom that encourage self-confidence and collaborative work.

The guidelines of the teaching programme set out achievable goals in each of the phases of the process oriented towards avoiding creative blocks, and if this was the case, as was seen, it could be resolved with the lecturer’s support. In this way, we have seen that the student also learns from their mistakes and is conscious that they are responsible for their learning.

6. Conclusions

This investigation responds to the initial objectives. The primary goal of designing a teaching methodology for the Creative Advertising subject has been resolved in section 3 of this article. We have also reached the specific objectives proposed for implementing teaching innovation (section 4), as seen below:

- SO1 proposed simulating real work in the classroom, experience achieved through implementing a PBL methodology that adopts the timeline and themes of the phases of the creativa process in advertising. The designed programme allows the student to explore and experience the different roles and professional profiles. This favours identifying what functional aspects of the profession are more attractive according to their interests and potentialities. The students become aware of the professional areas for themselves.

- SO2 proposes designing an eminently practical learning method, which has also been reached through the students’ different milestones in each phase of the project, which leads directly to achieving SO3, insisting on teaching the students accessible techniques and tools for creating and solving real cases.

- SO4 and SO5 refer to the development of creative abilities, the ability to work in a team, make decisions, and take responsibility for their own learning. According to what has been verified in the implementation results, these objectives have also been reached.

Achieving the objectives thus leads us to verify the initial hypothesis: the viability of integrating the narration as a didactic resource for creatives, which has been confirmed after implementing and evaluating the lecturer’s experience.

Finally, we must highlight that the method designed is presented as an alternative to a lecture in Creative Advertising subject and other similar subjects. It could be helpful in subjects such as Advertising Art Direction, Copywriting or Strategic Advertising Planning since the training programme itself follows the sequentiality of work in advertising. Although they have specific objectives, these subjects are key in advertising production. Therefore the contents can be adapted to the timing of the didactic phases.

Likewise, this research lends itself to new phases and improvements in several aspects from now on. On the one hand, a new cycle of action research is proposed to counteract the deficiencies found in the techniques used, and quantitative evaluation methods are contemplated for each of the tools used. Both perspectives will be covered in future research focused on improving the teaching-learning experience in creativity in advertising at the university level.

7. Acknowledgements

To María José Bogas Ríos for her advice on research methods in education.

To Sophie Phillips for translating this article into English.

8. Funding

The results of this research are part of the project “Narrative strategies of advertising creation” funded by the III Convocatoria de fomento de la innovación y mejora de la docencia 2021 promoted by the Vicedean de Extensión Universitaria y Relaciones Internacionales from the Faculty of Communication Sciences from Rey Juan Carlos University.