1. Introduction

The Arab Spring was one of the most unpredictable political episodes of recent times (Atlas, 2012). Above all, having developed in a region characterized by an iron control of information, with freedom of the press and expression widely restricted (García-Marín, 2017). And then, because it invalidated the theses which claimed it was highly unlikely that Arab societies were the epicenter of great social mobilizations. In other words, culturalist postulates who spoke of Islamic exceptionalism (Abu-Tarbush, 2015: 31). Of course, the protests which began at the end of 2010 have given rise to an enormous amount of academic literature from various disciplines, among which, obviously, there is no lack of political science and, specifically, political communication (Durán-Cenit and García-Marín, 2015; Altourah, Chen and Al-Kandari, 2021).

One of the most talked about elements of the Arab Spring was the role played by the media and, above all, social networks (Meraz and Papacharissi, 2013). The self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi in Tunisia was not the first, nor the only, of the year, but it was the one which triggered the mobilizations which overthrew the Ben Ali regime, and subsequently spread throughout the region. The explanation is perhaps found in the information addressed to the international press, although not to citizens (Martínez-Fuentes, 2011) thus conjoining two extraordinary events, social networks (internal) and media (external). This fact is really important if we take into account that many of the international journalists were prohibited from entering the Maghreb country. A ban which also occurred in other countries, such as in Syria at the beginning of the revolution.

Currently, the area continues to have very restrictive scores in terms of social rights and civil liberties, except in the Tunisian case (Freedom House, 2020; The Economist, 2019); closing those debates which have speculated that there could be a fourth wave of democratization (Priego-Moreno, 2011). Although, it is true that the effects of the Arab Spring have affected virtually every country in the Arab-Muslim world. Effects that can be framed within a wave of political change (Szmolka, 2013). Of course, within the academic debate around the lessons learned from these revolts, the role of the media, the object of study of this research, must be included.

This research attempts to study how the headlines of the Spanish press have been constructed, specifically in the cases of El País, ABC, El Mundo and La Vanguardia, during the post-Arab Spring period (2012-2020). To this end, the press headlines of each media have been analyzed, exploring the frequency of news publication, the importance given to the different countries and the main frames when reporting on the region. In the opinion of the researchers, the analysis of headlines is pertinent, although they may not fully reflect the content of the news, the need for users to click on the links has favored the use of attractive and impactful headings ( popularly called clickbait). To do this, the unsupervised algorithm LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) will be used, as it is very useful to summarize large volumes of data with uniform texts.

The present paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, there will be a theoretical review of the importance of the media during the development of the Arab Spring. Subsequently, the methodological approach used and the main results of its application will be explained. Closing the investigation, the last section is dedicated to drawing the most relevant conclusions.

2. The Arab Spring and the media

The Arab Spring, or Arab Awakening, has been one of the most important events of political change of the twenty-first century. Nine years after the overthrow of Ben Ali in Tunisia, Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Abdullah Saleh in Yemen there are few elements which can affirm that there has been a democratization of the region (Álvarez-Ossorio, Barreñada-Bajo and Mijares-Molina, 2021). Even in recent years, mass protests in other countries, namely Algeria, Sudan, Lebanon and Iraq, where the first mobilizations took a back seat, have led to the debate about whether there is still a continuation of the Arab Spring or simply a new regional political development (Truevtsev, 2020). Although, the main indices on democracy and freedoms show skeptical results on this issue, authors such as El-Haddad (2020), claim that one of the effects of the Arab Spring has been the reconfiguration of the social contract between civil society and political elites.

One of the most important aspects when addressing the mobilizations in the Arab world has been the use of the media and social networks. However, it should be noted that there is no unanimous answer about its importance. In other words, in each country the media took on a different but interrelated role. For example, in the case of Tunisia, social networks served as an external information channel, with Al Jazeera being the first network to show almost all the videos which came from the country (Sarnelli, 2013). Meanwhile, in the case of Egypt, social networks not only supplied information but served as an organizing and coordinating factor. (Wilson and Dunn, 2011). However, several authors point out that the importance of the media and social networks as a democratizing way has been mythologized. In the words of Moldovan (2020): “The aftermath of the Arab Spring demonstrated that significant political change in the MENA1 region cannot be brought about by mobilization through social media and televised protests alone” (p. 268). Alluding to the need for other factors, such as a correct democratic political culture, control over the separation of powers, amongst many others.

Beyond the debate about the possible effects which could condition the development of the protests, an issue which has worried academics around the world has been how the media projected their image. Hence, we find a considerable amount of work on various issues with significant results. For example, Dastgeer and Gade (2016) point out how women played a leading role in the coverage of media such as Al Jazeera, despite the fact that the Arab media have a clear male orientation (Engineer, 2008). Meanwhile, Sik Ha and Shin (2019) indicate that Chinese media downplayed the accounts of citizens and social activists accusing Western nations of imposing a self-serving concept of order and security.

The revolts in the Arab world did not go unnoticed by the Spanish media either, although such coverage has not been without criticism. One element to highlight was the belated coverage of events in Tunisia, the epicentre of the protests. Corral-García and Fernández-Romero (2015) point out that the main Spanish press newspapers took more than a month, coinciding with the fall of Ben Ali, to publish the mobilizations on their front pages. And, in the case of TV3, in Catalonia, the use of social media as a source of information was practically non-existent (Elena and Tulloch, 2017) when they reported the protests against the Mubarak regime.

In general, it can be said that the Spanish press saw, in a positive way, the fall of dictatorial regimes (Sanz-Ocaña, 2018) although Irakrak (2017) adds that this image was conditioned to pre-established concepts about Arab society and culture. Pre-established images, which in some cases, transcend beyond the Arab Spring, see the case of Saudi Arabia (Omar Alsalem, 2016). However, the subsequent drifts in some countries, such as the war in Libya after the fall of Gaddafi, or the victory of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, has rescued the old pessimistic image that the Spanish media projected of the Arab countries (Vidal-Valiña, 2013). In other words, the Spanish newspapers supported the popular sectors when they mobilized against the established regimes, see the case of Libya, (Soria-Ibáñez, 2013), but framed the conflicts from other aspects (such as security), when these were prolonged, see the case of Syria (Moreno-Mercado, 2018).

If we review the most recent literature on the object of study, it can be inferred that the research focuses more on the consequences of the revolts than the foundations that came to motivate them. Among these consequences we highlight the appearance of Islamophobic discourses which point out the incompatibility of democracy with Islam as an explanatory factor (Corral, Fernández-Romero, García-Ortega, 2020), the frames used in the refugee issue (Sánchez-Castillo and Zarauza-Valero, 2020) or the informative interest on terrorist groups operating in countries of the Arab world (Plaza, Rivas-Nieto and Rey García, 2017), among others.

3. Methodology

This article has been based on a quantitative analysis, without abandoning qualitative elements, of the Spanish press; specifically in four newspapers of national circulation, El País, El Mundo, ABC and La Vanguardia in its digital version. This version allows us to have an important number of analysis units and adapt more to the digital reality of Spanish society (Luengo and Fernández-García, 2017). The study period covers 8 years, specifically from 2012 to 2020, taking as a reference the beginning of the year after the revolts of 2011. The selection of news has been extracted from the MyNews database, which has yielded a considerable sample (n = 4,629) which reflects a faithful image of the Spanish coverage during the post-Arab Spring period. Although this research aims to analyze the headlines, the following terms have been extracted from the news that appeared in the content: *Spring and *Arabic. The reason is not to over-limit the sample.

The study of press headlines has been a recurring element in research on political communication. According to Van Dijk (1990), these represent a concise and summarized image of the news and define the orientation of the medium before the question is raised. In our opinion, this study is very pertinent since the current informative logics suggest that the need to obtain visits and clicks has forced the media to elaborate more attractive headlines for audiences, a process which reaches almost all European media (Orosa, Santorum and García, 2017). In other words, the emotional element is being overlaid on the informational factor.

The extraction of topics from the headlines has been possible thanks to the automation of text analysis from the unsupervised algorithm LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation). LDA is probably the most widely used generative probabilistic model of the so-called Topic Models (Hovy, 2020). Before applying the algorithm the texts have been preprocessed (tokenized) eliminating elements that can alter the analysis. Among them, white spaces, scores, prepositions and common words (stopwords). The LDA algorithm allows you to group the headlines in certain clusters from the association of keywords that represent the main topic of each group. The model starts from the hypothesis that the person who writes a document has certain key issues in the mind (Ostrowiski, 2015). This is reflected graphically in a series of boxes inserted one on the other. “The boxes are “plates” that represent replicas. The outer plate represents the documents, while the inner plate represents the repeated choice of themes and words within the document” (Blei, Ng and Jordan, 2003: 997). That is, the task of the algorithm is simply to present a series of topics, at the choice of the researcher, which group words according to their frequency in them (and absence in other topics).

The software used has been Orange Data Mining, under Python 3, thanks to its usefulness to work with large volumes of data (text mining). This package allows multiple modalities, such as sentiment analysis, neural networks, topic models, Twitter data extraction, among many others (Demšar et al., 2013).

The topics extracted from the LDA analysis have been redefined under the classic premise of framing (Entman, 1993). These usually meet these four characteristics: 1) they define problems; 2) identify the causes; 3) propose solutions; 4) establish moral judgments. Although, in the case of this study, it has opted for the definition of the problem, since the Arab Spring is an event of international politics. Of course, this does not mean that the other characteristics are not present, but that the phenomena of foreign policies are usually raised from the delimitation of the problem as direct contact with the phenomenon addressed is much less plausible. In short, it has been chosen to structure the analysis in a simple but theoretically consistent way. The operationalization of frames has traditionally been carried out from the extraction of conglomerates or clusters. This operationalization has been conventionally proposed from classical research techniques, such as content and factor analysis. The proposed proposal goes a step further by allowing structured data to be extracted automatically and massively.

Therefore, the research question that this document raises is: How has the Spanish press’s treatment of the Arab reality been during the post-uprising period 2011? From here, we try to answer this question from the conjugation of political communication and computational science. The objective is to make an empirical contribution after more than nine years of the mobilizations. To do this, the study does not focus on a specific country, but aims to shed light on what issues the Spanish press has dealt with when it has reported in a general way on the Arab Spring. In short, to carry out an analysis of large volumes of information, which allow inferences to be made, without forgetting that the Arab world, encompasses 22 countries with very diverse political and sociological realities.

4. Findings

The development of the protests in the Arab world has left very different scenarios, depending on the country you want to analyze. These scenarios have also depended on their inclusion in the media agenda, some experiencing extraordinary coverage and others a smaller presence, leaving in some cases testimonial appearances. In other words, reporting on the waves of Syrian refugees and their impact on Europe has not been the same as Omar Al-Bashir’s departure from power in Sudan, a country geographically and culturally distant from Spain. This reality coincides with the study of Árdevol-Abreu (2015), where he affirms that the media privileges information on international politics which has an impact on national economic and strategic interests.

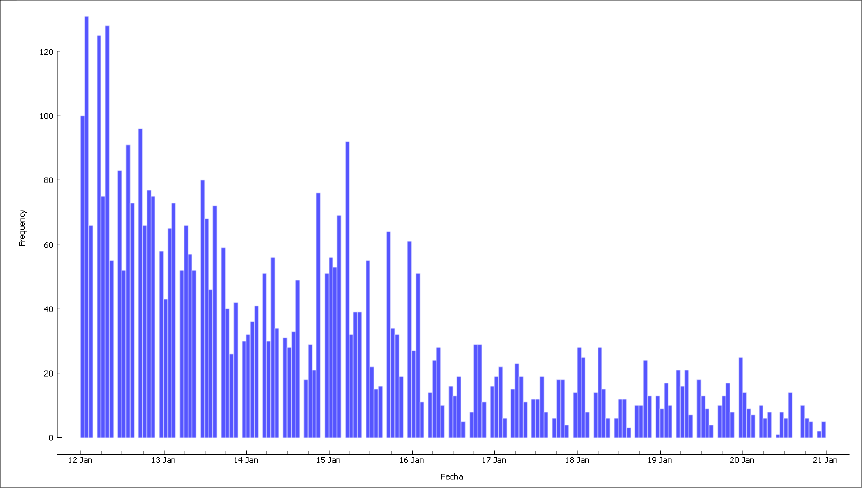

The first aspect of the media relevance of a political event is the number of appearances of that event in the media. In this regard, figure 1 visually shows the media relevance of the Arab Spring. As mentioned in the previous section, the graph is not a representation of the coverage of countries that experienced revolts, in some cases much higher than that shown here (such as the Syrian conflict), but at the times that the concept of Arab Spring was explicitly mentioned.

Coverage could be divided into three distinct stages. The first (2012-2014), is where the largest number of news is concentrated (especially in the first year). However, this concentration is not uniform, as there is a progressive decline in news, with small upswings, as the years develop. The upswings could refer to key moments in the political drift of the countries in question. For example, there is an increase in news in July 2013, when Mohammed Morsi was overthrown in Egypt. A second stage (2015-2016) marked by a new upward trend, although of less relevance if we compare it with the beginning of the first period. During this stage there are significant events in Europe such as the refugee crisis or attacks of great relevance, such as those in Paris or Brussels. And a third stage (2017-2020) which we could classify as a stable descent with small increases. These small promotions also coincide with very concrete political events, to name a few: January 2020, the death of the Sultan of Oman Qabus Bin Said Al-Said or April 2019 with the resignation of Abdelaziz Bouteflika in Algeria.

Figure 1. Evolution of post-Arab Spring coverage

Source: prepared by the authors

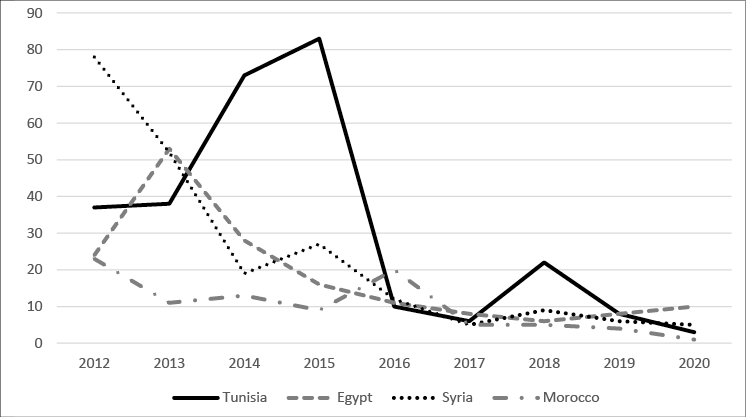

At this point, the question arises about which Arab countries have made the biggest headlines in the Spanish press. Figure 2 and Table 1 are quite clarifying about the importance that each media has given to political events in the Arab world. The results show a similar behavior without major differences between the media analyzed, suggesting that the reason lies in shared cultural elements. The table includes all Arab countries (in addition to Iran) which were mentioned once. The Arab countries which had no mention were Chad, Comoros and Mauritania. As in the division of periods, the presence of countries in the headlines can be divided into well-differentiated groups.

First of all, Tunisia is the most mentioned country in the media which was studied (except in the case of El Mundo). That its presence is majority, falls within the expected results since it was in the Maghreb country where the revolts began and later spread through the MENA region. In addition, the results obtained suggest that the Tunisian political process, as an issue on the media agenda, probably has specific journalistic dynamics. The possible explanations can be found in the way that Tunisia has been the only country which has obtained positive scores in the main democracy indices. Likewise, we consider that the Tunisian experience can present highly newsworthy elements since despite having produced legal reforms that suppose a greater guarantee in terms of public freedoms and civil rights (Pérez-Beltrán and García-Marín, 2015) the consolidation of democracy still presents important challenges (Farag, 2020).

Secondly, it should be noted the important coverage devoted to the case of Egypt, being after Tunisia and Syria, the third most mentioned country. It is difficult to establish strong statements in this regard since there is no extensive bibliography on the Egyptian subject. At first glance it can be established that the Egyptian case has been followed with great interest by the Spanish media. Something logical if we take into account that during this period President Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood was overthrown. This interest may be related, among other reasons, to the Spanish diplomatic rapprochement with the Cairo executive. In fact, Azzaola-Piazza and González-González (2017) point out that the behaviors of Spanish diplomacy towards the government of Abdel Fatah Al-Sisi are very similar to the period of Hosni Mubarak.

Thirdly, we can establish another bloc of countries which have experienced armed conflicts which persist today. As can be seen, Syria is the second country which devotes the most headlines to the press. The differences with Yemen are significant, although in our view, the poor results on Libya are powerfully striking. The most plausible explanation may be the difficulty of the press to report on this conflict since neither the government of Spain nor the European Union have shown a unanimous position towards it. In addition, Spanish coverage of the Libyan conflict has been very uneven, experiencing its moments of maximum media attention with dramatic humanitarian events (Moreno-Mercado, Luengo and García-Marín, 2021).

Finally, in fourth place are the rest of the countries present in the coverage. Among these, the one with the most significant results is Morocco; something to be expected due to the geographical proximity and the multiple Spanish interests in the country. In addition, the regional powers that have a fundamental role in the political development of the Middle East, Saudi Arabia and Iran. The rest of the countries experience a minor role strongly dependent on political events of great significance, as in the cases of Algeria, Bahrain or Iraq.

Table 1. Frequency of countries in the headlines by newspaper

|

Country |

ABC |

El País |

El Mundo |

La Vanguardia |

Total |

|

Tunisia |

83 |

89 |

45 |

71 |

288 |

|

Syria |

49 |

50 |

60 |

61 |

220 |

|

Egypt |

34 |

40 |

46 |

52 |

172 |

|

Morocco |

30 |

29 |

22 |

17 |

98 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

16 |

20 |

16 |

16 |

68 |

|

Iran |

16 |

13 |

18 |

20 |

67 |

|

Yemen |

14 |

16 |

17 |

20 |

67 |

|

Libya |

12 |

19 |

9 |

15 |

55 |

|

Algeria |

5 |

18 |

17 |

7 |

47 |

|

Bahrain |

8 |

9 |

15 |

7 |

39 |

|

Western Sahara |

9 |

4 |

11 |

10 |

34 |

|

Jordan |

10 |

9 |

10 |

2 |

31 |

|

Iraq |

11 |

3 |

9 |

4 |

27 |

|

Qatar |

8 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

23 |

|

Kuwait |

3 |

6 |

8 |

4 |

21 |

|

Oman |

6 |

3 |

6 |

4 |

19 |

|

Lebanon |

5 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

17 |

|

Palestine |

2 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

17 |

|

UAE |

1 |

6 |

3 |

4 |

14 |

|

Sudan |

4 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

12 |

|

Djibouti |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Somalia |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Source: prepared by the authors

Figure 2. Presence of selected countries in the grouped headlines

Source: prepared by the authors

It should be noted that not only the amount of information and the actors mentioned is enough to be able to measure how the media behavior has been. The way of informing, and the topics discussed is one of the most important elements in any analysis of coverage and information dimension. Table 2 shows the main topics-frames extracted from the application of the LDA algorithm. The topics have been exposed from the framing theory, especially from the definition of the problem, as mentioned earlier in the methodological section. However, we want to emphasize that although the LDA is an illustrative technique, it could be convenient to combine it with other complementary techniques, such as vector support machines (SVM) to locate frames. One of the characteristics of the LDA model is that they must be applied to very uniform texts, which implies that some caution must be taken when establishing casualties. For this reason they should be used in an exploratory or descriptive way (objective of this work). From the extraction of topics that the Orange software allows (from one to twelve), we consider that three is the most pertinent number for this study after ruling out other possibilities. The reason is that the division of the sample into more topics did not yield more results that would increase the explanatory potential of the research. However, we must emphasize that, to give meaning to the research, the qualitative interpretation of the authors is necessary since the application of the model itself is not enough.

The first of these could be defined as the Syrian Conflict. The set of terms that composes it is quite clarifying in how the media have approached the problem of the Syrian crisis. Special emphasis is placed on the regime’s brutality in suppressing protests and thus the responsibility of President Bashar Al-Assad, as well as the involvement of regional actors such as Israel and Iran. The elements indicated here are clearly identifiable with generic frames such as Conflict, Security and Responsibility: “Syria, the first world war of the XXI century, El País, 15/03/19”, “Assad the monster without dictatorship, El Mundo, 12/03/12”, “Syria accuses Israel of bombing Damascus, La Vanguardia, 05/05/13”, “Iranian paramilitaries shield Al Assad, ABC, 03/04/14”.

The second issue, Islam, has extensive roots and professional routines in the Spanish press. In fact, if we pointed out before that the bibliography on Spanish coverage and Arab Spring is scarce, this is not the case, in the case of Islam. This issue is strongly related to the debate on whether Islam is compatible with the democratic development of Arab countries, hence Tunisia is an essential information element. On this issue, reports about the Tunisian elections and Ennahda candidates occupy an important place on the media agenda: “Tunisia elects a conservative Islamist as mayor, the first in the Arab world, ABC, 04/07/18”, “Tunisia after the Arab Spring, El País, 02/16/17”, “Tunisia shows that Islamist and secular movements can work together, El Mundo, 10/09/15”, “Islamist anger spreads with violent assaults in Tunisia and Sudan, La Vanguardia, 09/15/12”.

The third issue has been categorized as Regional Instability and refers to political developments in general in the Arab world. The terms it encompasses refer to the case of various countries and the different effects that the Arab Spring has had on them. Unlike the other two, we could say that it is a more generic theme about the reality in the Arab world: “The 20 years of Mohammed VI on the throne of Morocco: from courageous openness to stagnation, El País, 28/07/19”, “The plagues that await Al Sisi in Egypt, El Mundo, 27/05/14”, “They arrest the opposition leader in Bahrain, El Mundo, 29/12/13”, “Violence comes to the Revolt of the Rif, ABC, 17/06/17”.

Table 2. LDA Analysis

|

Priority |

Syrian Conflict |

Islam |

Regional Instability |

|

1 |

“Syria” |

“Arab” |

“Syria” |

|

2 |

“Deaths” |

“Spring” |

“Year” |

|

3 |

“Israel” |

“Islam” |

“Morocco” |

|

4 |

“Iran” |

“World” |

“Egypt” |

|

5 |

“EEUU” |

“Elections” |

“New” |

|

6 |

“Government” |

“Tunisia” |

“Bahrain” |

|

7 |

“Assad” |

“Democracy” |

“Delation” |

|

8 |

“Weapons” |

“Revolution” |

“Uprising” |

|

9 |

“Regime” |

“Crisis” |

“2011” |

Source: prepared by the authors

Finally, it was considered relevant to see if the four media used similar or different language when constructing their headings. To shed light on this question, a simple analysis of frequencies was carried out by means, materialized in Table 3. The results show a very similar use of language although we can highlight some differences. First, how in the case of La Vanguardia the terms “tourists” and “Obama” appear. These results indicate that the economic and international aspects have a significant relevance: “Tourists can already make “selfies” for free with the mummies of Egypt, La Vanguardia, 01/08/19”, “Obama takes a first step to channel relations with the Persian Gulf, La Vanguardia, 05/15/15”. And, second, the importance of Saudi Arabia in the case of El País is highlighted. This importance translates into the relevance of the House of Saud in the regional environment as well as a critical approach to the country’s policies: “Iran measures its forces with Saudi Arabia in the Middle East, El País, 28/03/15”, “Amnesty documents the harassment of civilian activists in Saudi Arabia, El País, 10/10/14”.

Table 3. Ten most used terms by newspaper

|

ABC |

El País |

El Mundo |

La Vanguardia |

||||||||

|

Term |

n |

% |

Term |

n |

% |

Term |

n |

% |

Term |

n |

% |

|

Arab |

98 |

8.91 |

Tunisia |

89 |

9.05 |

Syria |

80 |

6.21 |

Arab |

101 |

8.00 |

|

Tunisia |

83 |

7.55 |

Syria |

65 |

7.27 |

Arab |

53 |

4.11 |

Syria |

84 |

6.65 |

|

Spring |

76 |

6.91 |

Arab |

56 |

5.69 |

Spring |

50 |

3.88 |

Spring |

72 |

5.70 |

|

Syria |

66 |

6.00 |

Islam |

56 |

5.69 |

Egypt |

45 |

3.49 |

Tunisia |

71 |

5.62 |

|

New |

43 |

3.91 |

Spring |

44 |

4.47 |

Tunisia |

45 |

3.49 |

Egypt |

52 |

4.12 |

|

Spain |

41 |

3.73 |

Egypt |

40 |

4.06 |

Deaths |

44 |

3.41 |

Country |

39 |

3.09 |

|

Deaths |

39 |

3.54 |

New |

33 |

3.35 |

Egyptian |

38 |

2.95 |

Tourists |

36 |

2.85 |

|

Years |

35 |

3.18 |

Politics |

30 |

3.05 |

Years |

34 |

2.64 |

Years |

34 |

2.69 |

|

Egypt |

34 |

3.09 |

Saudi |

30 |

3.05 |

Islam |

33 |

2.56 |

Obama |

34 |

2.69 |

|

Morocco |

30 |

2.72 |

Morocco |

29 |

2.95 |

Spain |

33 |

2.56 |

World |

33 |

2.61 |

Source: prepared by the authors

5. Discussion and conclusions

This research has had two clearly differentiated but compatible objectives: on the one hand, to prove that the new quantitative analyses are useful to, at least, describe the reality that surrounds us. Although, we again highlight the need for authors to find an explanatory meaning to the data extracted from automatic processing. And, on the other hand, that the media usually behave according to shared cultural references when there are no underlying ideological differences (one of the theses of the indexing theory proposed by Lance Bennett, see, for example, his definition of 2015). The combination of both, has served to show, in broad strokes, the coverage of the selected Spanish media on the Arab Spring (whatever the meaning of the term) for eight years. In this regard, the analysis does not yield great surprises: the media analyzed covered on more occasions and in a deeper way, those striking and culturally close events. Data which invites us to think that the principles of gatekeeping are still as valid now as they were 70 years ago when they were proposed. An absence of surprises which can constitute a wake-up call. The information which citizens receive, even in this time of information overabundance, continues to be governed by patterns which limit its scope: there are still gaps, stereotypes and, in this case at least, a patent absence of pluralism. Although these conclusions may be due to the specific choice of the sample chosen, we consider that it is an element which should invite academic reflection in future research.

Indeed, the information that the selected media have produced can be characterized by being very similar, to the point that, with only three groupings of terms (elaborated by the algorithm) we can summarize the coverage for eight years of four apparently diverse newspapers, although with common singularities. Actually, there are countries which are barely mentioned, even when examples of political change are recurrent and the government reaction is very violent, as is the case in Bahrain. These are data that invite reflection on the quality and variety of the information available to citizens and the prejudices and value judgments that may give rise. In this sense, we can establish that this research aims to shed light on an object of study that has had more statements than demonstrations. In fact, it can be framed within the general reflection of where international journalism is going in the Spanish media complex. In conclusion, this work can help the scientific debate about the lessons learned and the challenges posed by Spain’s relations with the Arab world after the 2011 revolts. Debate that is still very current within the Spanish academy as evidenced by works and scientific meetings of recent elaboration, such as Movilizaciones populares tras las Primaveras Árabes (2011-2021).

Likewise, as we have mentioned, one of the contributions we intend to make with this research is methodological. At present the number of media has multiplied and the channels through which they broadcast are digital. This makes it unstructured information, in text form, and available to researchers. See the ability to extract large volumes of data from digital media (via MyNews or Lexis UNI) and social networks, such as Twitter (REST API) but which need to be treated and categorized. Never before have academics had so much information or so much capacity for analysis at a ridiculous price. Therefore, methodological techniques must necessarily adapt to a new, varied environment in which the analysis on a medium or channel is becoming less and less significant. It is necessary to expand the data set to have an accurate picture of the informative (or social) reality. Of course, this methodological innovation has been accompanied by technological development in recent years. So we can say that this work uses a current methodology in a field of research (international communication) which still suffers from ambitious quantitative studies. What we propose here is nothing more than an exploratory, descriptive, but valid technique to make that type of work increasingly common among the scientific community. Classification and analysis algorithms (supervised or not) and the so-called artificial intelligence must become common tools for researchers in the social sciences. Only in this way will we be able to approach increasingly fragmented and digital realities.

6. Acknowledgments

Laura Jane Aitken has translated this article into English.