1. Introduction and review of the literature

The analysis of disinformation and fake news has been a major trend in recent years in scientific research in several fields. Since Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 election and the Brexit referendum in United Kingdom, the bulk of researchers’ attention has gone to revealing the causes, formal characteristics, production and propagation patterns as well as possible solutions to the phenomenon, seen as one of current democracies’ biggest problems (Elías, 2021). In liberal democratic systems, interest in disinformation “lies in its presumed capacity to raise levels of political polarization, and at the end of the day, damage the principals which underpin coexistence“ (Fernández-Roldán, 2021: 60), this explaining the concern this problem causes among scientists, particularly in the field of communication.

Though digital environments were initially welcomed as offering emancipating and democratic possibilities (Jenkins, 2006; Shirky, 2010) and to drive social movements (Castells, 2012) and the blossoming of so-called “citizen journalism” (Gillmor, 2004), over the last five years there has been a proliferation of research which places new digital technical developments applied to communication as one of the chief causes of the current phenomenon of disinformation. Most of these studies have focused on how to put a stop to the production and diffusion of false content in digital spaces (Margolin, Hannak & Weber, 2018; Zhang et al., 2019), the analysis of disinformation campaigns in virtual settings (Endsley, 2018) and how to detect false rumours on social networks (Zubiaga et al., 2018). These studies also cover the evaluation of the quality of the sources in these environments (Kim, Moravec & Dennis, 2019; Pennycook & Rand, 2019) and even, the appropriateness of censuring content on these platforms (Citron, 2018).

Research into disinformation has also looked kindly on technology, seeing digital tools as allies in the struggle against disinformation. In fact, an increasingly important area of analysis in recent years has been the effectiveness of algorithms and automated solutions for the detection of fake news (Soe, 2018; Ko et al., 2019). Some of these studies, such as that of Del Vicario et al. (2019), focus on the analysis of predictive models which help to better understand the production patterns of fake news. Research into the detection of false content on the networks has been particularly prolific, building on proposals for automatic identification and visualization tools for fake news (Shu, Mahudeswaran & Liu, 2019). These approaches have come from two points of view. Firstly, there are numerous studies which analyse content characteristics in order to train the algorithms in the detection of disinformation via machine learning techniques (Wang et al, 2018), textual analysis (Horne & Adali, 2017), stylometric tools (Potthast et al., 2018) and quantitative methods for an evaluation of the message’s credibility (Fairbanks et al., 2018). Other work proposes deep learning techniques as an approach for the identification of malicious content (Riedel et al., 2017; Popat et al., 2018). Secondly, studies focused on the detection of disinformation from the contextual characteristics of its place of production (Tacchini et al., 2017; Volkova et al., 2017) and circulation (Wu & Liu, 2018).

Also within the area of technology, studies by Fletcher, Schifferes and Thurman (2020) seek to analyse the effectiveness of algorithms in performing automated evaluations of source credibility. Other research in the same field has focused on algorithmic moderation of content (Gorwa, Binns & Katzenbach, 2020), the use of big data to detect disinformation (Torabi-Asr & Taboada, 2019), the automatic identification of bots in digital contexts (Beskow & Carley, 2019) and the applications of the blockchain against false information (Chen et al., 2020).

Apart from the technological implications of this phenomenon, the communication strategies used to fight against disinformation have also generated a considerable number of studies. Specifically, these studies have analysed the effective communication of science (Rose, 2018), counterpropaganda against disinformation campaigns in certain countries (Haigh, Haigh & Kozak, 2018) or how to combat populist discourse (Bosworth, 2019). A large number of the papers on this question focus on the role of the media in disinformation crises, in particular as regards fact-checking. Numerous studies have been caried out in this field about the efficacy of these entities in disproving fake news concerning science (Peter & Koch, 2016), health (Vraga & Bode, 2017), and in electoral (Nyhan et al., 2020) and highly polarized contexts (Zollo et al., 2017). The study of fact-checking has also been done from an analysis of its mechanisms of transparency when explaining the verification process to citizens (Humprecht, 2020), its effects on politicians’ credibility (Agadjanian et al., 2019) or the use of social networks or real-time messaging services (Bernal-Triviño & Clares-Gavilan, 2019). Other research has evaluated the role of collaborative investigative journalism (Carson y Farhall, 2018), the establishment of limits and journalistic standards that can contribute to clearly differentiating between true information and content that is malicious and of doubtful quality (Luengo & García-Marín, 2020), strategies that the media themselves can put into place to improve their credibility and citizens’ trust (Vos & Thomas, 2018; Pickard, 2020) and the adoption of more horizontal and participative communication models for their relationship with their audiences (Meier, Kraus & Michaeler, 2018).

As we can see, disinformation is an object of study that can be analysed from different perspectives and areas of knowledge. The multidimensional character of the phenomenon (Aparici & García-Marín, 2019) requires the adoption of approaches from different fields, as well as that of communication (and in combination with this latter), such as computational sciences, psychology, sociology or education. Citizens, different levels of government, researchers, technology companies and news organizations must, therefore, join forces to mitigate false content which circulates in digital spaces and the traditional media (Dahlgren, 2018).

The need to implement digital and news literacy programmes using critical pedagogy (Higdon, 2020) has considerable presence in research into this question. The contributions of Roozenbeek and Van der Linden (2019) as well as Roozenbeek et al. (2020) stand out here. They studied the effectiveness of inoculation strategies in putting citizens in the place of the creators of disinformation with the object of detecting it. From a more general perspective, other researchers have demonstrated the efficiency of news literacy projects in the fight against malicious content (Amazeen & Bucy, 2019), on social networks such as Twitter (Vraga, Bode & Tully, 2020) and in specific countries, such as United States and India (Guess et al., 2020). Khan & Idris (2019) have shown the correlation between the news education of the population and their capacity to identify fake news, while other studies such as those of Gómez-Suárez (2017) and Buckingham (2019) put the onus on the importance of critical thinking in any media education project against malicious content. Additionally, the outbreak since early 2020 of made-up and misleading news about Covid-19 has led to calls for action to be taken to strengthen citizens’ scientific education (Hughes, 2019; López-Borrull, 2020; Sharon & Baram-Tsabari, 2020).

In recent years, there have also been numerous studies into the regulatory frameworks which some countries have introduced to minimize the impact of fake news, especially in digital media (Baade, 2018; Perl, Howlett & Ramesh, 2018). A smaller number of papers have looked at the role of libraries as content curators (Walter et al., 2020), action designed to regain trust in and the credibility of political (Hunt, Wang & Zhuang, 2020), social (Bjola & Papadakis, 2020) and educational institutions, and the ethical implications of the struggle against disinformation (Bjola, 2018).

This prolific academic output over the past five years has favoured the publication of numerous reviews of the scientific literature focused on the study of disinformation. Some of this work, such as that of Tandoc (2019) and Jankowski (2018), has been performed non-systematically. The -few- systematic reviews are characterised by their wide range of subjects and approaches. Of particular interest are those studies on fake news (Ha, Andreu-Pérez & Ray, 2019), research into fact-checking (Chan et al., 2017; Nieminen & Rapeli, 2019), analysis of disinformation in the social media (Pierri & Ceri, 2019), false product reviews in the framework of electronic commerce (Wu et al., 2020) and, finally, definitions of the different types of disinformation in order to draw up a unified classification of information disorders (Kapantai et al., 2020).

In line with these studies, ours consists of a systematic literature review (SLR) concerning the phenomenon of disinformation, from a general and quantitative perspective. However, as explained in the following section, our study presents clear differences from previous work of this nature. On one hand, it is not focused on one single aspect of the question but covers it from a multi-dimensional and multi-disciplinary viewpoint, integrating various perspectives and areas of study. Moreover, the sample includes a far higher number of papers analysed (n=605) than in the aforementioned reviews. Finally, it integrates a statistical analysis of the impact of this research (measured by the number of references made and normalised by the respective year of publication) from the intersection of several variables: subject matter, fields of study, types of work and country of origin.

2. Research questions & methodology

Our work, eminently quantitative, seeks to answer the following questions:

- Q1. What topics were researched in the field of disinformation over the period 2016-2020? Which had most impact (number of references made and normalised by year of publication)? Is the topic under research a determinant variable of the impact?

- Q2. What is the frequency of these studies by year of publication? Which topics were published most each year?

- Q3. Which fields of knowledge conduct studies on disinformation? Which have most impact? Is the field of knowledge a determining variable on the impact of the work?

- Q4. What types of studies are they and what methodology is utilised? Which types have greatest impact? Is the type of work a determinant variable on the impact?

- Q5. In which countries are most studies carried out? Which accumulate most impact? Is a study’s country of origin a determining variable on its impact?

- Q6. Which are the most frequent case studies? Is the carrying-out of the case studies a determinant variable of their impact?

- Q7. Which types of work and research methodologies are used in the different countries?

- Q8. What types of work / methodologies are used depending on the topic under study?

To answer these questions, a systematic literature review has been performed following the principles proposed by Kitchenham (2004), characterized by transparency and systemization in each of its phases (Codina, 2020). This approach allows us to deeply study, to evaluate and to interpret the scientific work conducted on a specific object of study in a previously established timeframe (Ramírez-Montoya & García-Peñalvo, 2018).

Our methodological process was based on the contributions of Higgins et al. (2019), Brereton et al. (2007) and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination of York University (2009), which divide studies with systematic reviews into three stages: (1) work planning from a pre-ordained definition of a series of research questions, (2) carrying-out of a documentary search and the creation of a definitive data base following the application of a set of criteria for inclusion and exclusion, and (3) drawing-up of a results report to answer the previously established questions.

To identify the articles to be analysed, we focused our study on the Web of Science (WoS) data base. Just as in previous studies of a similar nature, such as that of López-García et al. (2019), we use this data base exclusively as it is the most relevant scientifically and because it seeks to gather together research published in the journals of greatest impact and visibility internationally. For the first stage of compiling publications, the following criteria of inclusion were adopted:

- Studies published in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) data base of WoS.

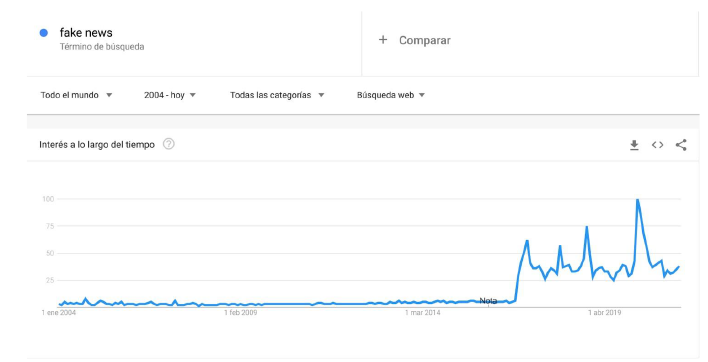

- Period of publication: 2016-2020. 2016 was chosen as our start point as it saw the emergence of this phenomenon as we now know it (Aparici & García-Marín, 2019), with Donald Trump’s victory in the American presidential election and the Brexit referendum in United Kingdom. The term post-truth was elected word of the year by the Oxford English Dictionary. Following Trump’s victory in late 2016, use of the term fake news “started to become common in the media, and from there, in society in general” (Rodríguez-Fernández, 2021: 48), as shown by the graph of searches for the term on Google between January 2004 and May 2021 (figure 1). The growth in the number of searches became significant from November 2016.

- Studies that approach any aspect of the phenomenon of disinformation and from any field of knowledge (communication, psychology, sociology, education, political science, etc.).

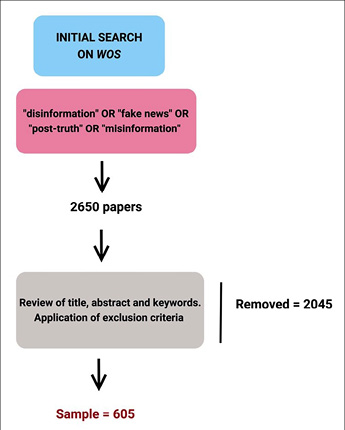

- Inclusion in the title, abstract or keywords of at least one of the following terms: “disinformation”, “fake news”, “post-truth” or “misinformation”. To this end, advanced searches were made using the Boolean data type operators: “disinformation” OR “fake news” OR “post-truth” OR “misinformation”.

- Not only empirical work was included, but also studies of theoretical review and essays published by scientific journals.

The initial compilation of papers took place on December 7, 2020. 2650 publications were amassed (figure 2), which were then analysed by an exhaustive review of the title, abstract and keywords. From this first corpus of papers, a filtering process took place using two criteria of exclusion:

- Editorials presenting monographs and special editions.

- Papers not related to the object of our study were excluded, although they may have included some of the search terms. The search for the term “misinformation” was particularly problematic, as the concept encompasses papers on how some collectives (people with disability, for example) establish communication, and communication with non-human actors (information transmission between machines and/or digital technological devices), considerations that have nothing to do with the object of our study. Numerous papers containing the term “post-truth” were also discarded as the word is employed in many articles to characterise current times, but, in reality, were not dealing with disinformation.

Following the review phase, the definitive sample was reduced to 605 papers. Coding categories were now identified (see table 1) for each of the seven variables present in our research questions: (1) subject, (2) year of publication, (3) areas of study, (4) types of study / methodology, (5) country of origin of the study, (6) case studies and (7) normalised impact. In the case of countries of origin, the nationality of the institution of the lead researcher was taken as a reference. The data extracted was analysed using descriptive and referential statistics with the SPSS v.26 statistical package.

To measure the studies’ impact, the absolute number of references received was not used, in order to avoid distortions deriving from the year of publication. In its place, the number of references to each article was relativized with regard to the average number of references in each of the publication years (2016, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020). This average of annual references was taken from the sample analysed. Therefore, the normalised impact of each article is the result of dividing the number of references by the average number of references in its year of publication. It was decided to normalise the impact using this procedure instead of utilizing the figure for worldwide references in that specific area of knowledge due to the non-availability of such data corresponding to the years 2019 and 2020 (see the updated tables of worldwide references at this link: https://cutt.ly/3Ejykus).

Figure 1. Searches for the term “fake news” in Google between January 2004 and May 2021

Source: Google Trends

Figure 2. Process of systematic review adopted for this paper

Table 1. The relationship of each variable to its coding categories

|

Variable |

Coding category |

|

Subject |

General Solutions & strategies Cognitive & ideological bias Production of disinformation Consequences / impact Propagation of misleading content Causes of disinformation Definitions of key concepts Perceptions of disinformation Role of journalism Emotions & disinformation Deepfakes Negationism Cybersecurity |

|

Year |

2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 |

|

Academic field |

Communication (no related area) Psychology Politics Analysis of social networks Health Education Science Sociology Philosophy Economics |

|

Type of study / methodology |

Quantitative Experiment Qualitative Mixed (quantitative-qualitative) Review of theory Essay |

|

Country |

The country of affiliation of the researcher who signed the article was taken into consideration |

|

Case study |

Yes / No. Indicate the case. |

|

Normalised impact |

Number of times the article was cited as of 07/12/2020, divided by the average number of references in the year it was published (obtained from the sample). |

Source: created by the author

To perform the inferential statistical calculations and, that way, check for the existence of significant differences in the variables of the study, we had previously carried out a normality test of the sample in terms of normalised impact. This is necessary to choose the application of parametric and nonparametric tests in the statistical calculations. Kolgomorov-Smirnov tests were performed to determine the absence of normal distributions in the variable relative to the normalised impact of the studies (p < .01). It was decided to use Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U nonparametric tests for this, to discover major differences on the impact in terms of the different categories of the variables, and, where necessary, to conduct multiple comparisons between these categories.

3. Results

Given the number of questions our study seeks to answer and with the aim of easing understanding of this section, the results are presented after first introducing the relevant research question.

Q1. What topics were researched in the field of disinformation over the period 2016-2020? Which had most impact (number of references made and normalised by year of publication)? Is the topic under research a determinant variable of the impact?

The most prevalent studies are those that analyse possible solutions and strategies for dealing with the problem of disinformation (n=144; 23.80%) (table 2). These studies focus on a total of 12 subcategories: (1) solutions related to social networks and platforms, (2) communication strategies, (3) the role of the media, (4) policies against disinformation, (5) technological, algorithmic and automated solutions, (6) education against fake news, (7) the role of libraries, (8) the regaining of trust in institutions, (9) the role of art against disinformation, (10) ethical implications in the fight against fake news, (11) fact-checking and evaluation of news sources and (12) meta-analysis of the proposed solutions. The appendix features all the solutions and strategies against disinformation covered by the studies analysed.

Table 2. Average and standard deviation from the normalised impact by subject

|

Subject |

Frequency |

Normalised Impact |

|

|

Average |

SD |

||

|

Solutions & strategies |

144 (23.80%) |

0.84 |

0.92 |

|

Cognitive bias |

119 (19.67%) |

0.96 |

1.41 |

|

Production |

84 (13.88%) |

0.69 |

0.78 |

|

Consequences. impact |

57 (9.42%) |

1.17 |

1.91 |

|

Propagation |

47 (7.77%) |

2.29 |

5.38 |

|

Causes |

46 (7.60%) |

0.90 |

0.99 |

|

General |

34 (5.62%) |

0.95 |

1.25 |

|

Definitions |

22 (3.63%) |

1.33 |

2.24 |

|

Perceptions (of disinformation) |

22 (3.63%) |

0.73 |

0.73 |

|

Role of journalism |

11 (1.81%) |

0.38 |

0.19 |

|

Emotions |

7 (1.16%) |

0.45 |

0.31 |

|

Negationism |

5 (0.82%) |

0.65 |

0.50 |

|

Deepfakes |

5 (0.82%) |

0.91 |

0.48 |

|

Cybersecurity |

2 (0.33%) |

0.43 |

0.41 |

|

p value (χ2) |

< .00* |

||

|

p value (Kruskal-Wallis) |

.19** |

||

* Very significant differences are observed when p < .01.

** Significant differences are observed when p < .05.

Source: created by the author

After solutions, the most common studies are those related to cognitive and ideological bias (n=119; 19.67%). The analyses of the production mechanisms of disinformation come to 13.88% of the studies (n=84), while those relative to the repercussions or consequences of the question make up 9.42% (n=57). Chi-squared distribution tests determine highly significant differences in the frequency of this variable [χ2(13, N = 605) = 595.41, p < .00].

The papers with the greatest impact are those which address propagation patterns of false content (M=2.29; SD=5.38). In the next place are the studies which analyse the definitions of the key concepts related to this question (fake news, disinformation, post-truth, information disorders, etc.) from a theorical perspective, with an average impact of 1.33 and a standard deviation of 2.24. The studies on the consequences or repercussions of disinformation form the third most referenced topic (M=1.17; SD=1.91). The Kruskal-Wallis tests observe that the topic of a study does not constitute an important variable of its impact [H(13) = 17.12, p = .19].

Q2. What is the frequency of these studies by year of publication? Which topics were published most each year?

Studies on disinformation published in WoS have grown in number during the period 2016-2020. 37 studies published in 2016 have been compiled (6.11%), 84 in 2017 (13.88%), 151 in 2018 (24.95%), 198 in 2019 (32.72%) and 135 in 2020 (22.31%). Between 2016 and 2020, research published on this object of study multiplied five-fold.

Table 3 covers the topics in our sample by year. Two opposing tendencies stand out. On one hand, the percentage of studies on solutions and strategies against disinformation grew notably over the period. This topic represented 8.10% of the studies published in 2016, while by 2020 this aspect was addressed in 28.89% of that year’s research. In the opposite direction, the percentage of papers on cognitive bias, which made up 35.13% of research in 2016 had fallen considerably to only 17.03% by 2020. We infer from this that before the proliferation of studies on disinformation that started in 2017, there was already notable interest in psychological bias and news credibility.

Table 3. Number of papers published by topic over the period 2016-2020. The relative frequencies refer to

the percentage of papers published on the topic in that year

|

Topic |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Causes |

2 (5.40%) |

9 (10.71%) |

14 (9.27%) |

17 (8.58%) |

4 (2.96%) |

|

Consequences, impact |

2 (5.40%) |

6 (7.14%) |

15 (9.93%) |

16 (8.08%) |

18 (13.33%) |

|

Definitions |

0 (0.00%) |

5 (5.95%) |

10 (6.62%) |

5 (2.52%) |

2 (1.48%) |

|

Propagation |

4 (10.81%) |

7 (8.33%) |

9 (5.96%) |

16 (8.08%) |

11 (8.14%) |

|

Cognitive bias |

13 (35.13%) |

24 (28.57%) |

23 (15.23%) |

36 (18.18%) |

23 (17.03%) |

|

Solutions & strategies |

3 (8.10%) |

13 (15.47%) |

36 (23.84%) |

53 (26.76%) |

39 (28.89%) |

|

General |

0 (0.00%) |

5 (5.95%) |

9 (5.96%) |

14 (7.07%) |

6 (4.44%) |

|

Production |

6 (16.21%) |

7 (8.33%) |

23 (15.23%) |

24 (12.72%) |

24 (17.78%) |

|

Perceptions |

3 (8.10%) |

4 (4.76%) |

6 (3.97%) |

7 (3.53%) |

2 (1.48%) |

|

Negationism |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (1.19%) |

1 (0.66%) |

3 (1.51%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

Role of journalism |

1 (2.70%) |

1 (1.19%) |

3 (1.98%) |

3 (1.51%) |

3 (2.22%) |

|

Emotions |

3 (8.10%) |

2 (2.38%) |

1 (0.66%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (0.74%) |

|

Deepfakes |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

3 (1.51%) |

2 (1.48%) |

|

Cybersecurity |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (0.66%) |

1 (0.50%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

Total |

37 |

84 |

151 |

198 |

135 |

Source: created by the author

Q3. Which fields of knowledge conduct studies on disinformation? Which have most impact? Is the field of knowledge a determining variable on the impact of the work?

Very clear differences can be seen in the number of studies by area of knowledge [χ2(9, N = 605) = 310.62, p < .00]. The field of psychology (especially the studies on cognitive biases) is the area which has provided the highest number of papers (n=131; 21.65%) (table 4). Research from political science (n=119; 19.67%) and studies about social networks (n=112; 18.51%) have also been prominent. Following them, come papers on health (n=71; 11.73%), doubtless as a consequence of the proliferation of research analysing disinformation deriving from the Covid-19 pandemic, a matter greatly studied throughout 2020.

It is precisely these papers from the health field which have the greatest impact (M=1.17; SD=1.39). Studies about disinformation on social networks and digital platforms also had a major impact (M=1.13; SD=3.33) as well as those relative to politics (M=1.10; SD=1.90). Papers found exclusively in the area of communication (therefore, without another related area) reached an average impact of 1.05 (SD=1.66). The nonparametric tests conducted determine that the field of study is not a relevant factor in the impact of these papers [H(9) = 13.60, p = .13].

Table 4. Average and standard deviation of the normalised impact by fields of knowledge

|

Areas |

Frequencies |

Normalised Impact |

|

|

Average |

SD |

||

|

Psychology |

131 (21.65%) |

0.92 |

1.36 |

|

Politics |

119 (19.67%) |

1.10 |

1.90 |

|

Networks |

112 (18.51%) |

1.13 |

3.33 |

|

Health |

71 (11.73%) |

1.17 |

1.39 |

|

Communication (no related area) |

56 (9.25%) |

1.05 |

1.66 |

|

Education |

38 (6.28%) |

0.70 |

0.59 |

|

Science |

32 (5.29%) |

1.04 |

1.12 |

|

Sociology |

26 (4.29%) |

0.52 |

0.41 |

|

Philosophy |

12 (1.98%) |

0.42 |

0.30 |

|

Economics |

8 (1.32%) |

0.80 |

0.44 |

|

p value (χ2) |

< .00* |

||

|

p value (Kruskal-Wallis) |

.13** |

||

*Highly significant differences are observed when p < .01.

** Significant differences are observed when p < .05.

Source: created by the author

Q4. What types of studies are they and what methodology is utilised? Which types have greatest impact? Is the type of work a determinant variable on the impact?

The essay is the commonest type of paper (n=168; 27.77%), followed by quantitative (n=159; 26.28%) and experimental studies (n=135; 22.31%) (table 5). Note that experiments are also quantitative, and therefore quantitative methodologies appear in almost half of the sample analysed (48.59%). The publication of qualitative studies is far less frequent (n=55; 9.09%) as is that of those conducted with mixed methodologies (articulation of qualitative and quantitative methods) (n=48; 7.93%). As occurred in the case of topics and areas of knowledge, there are highly significant differences in the frequencies of this variable [χ2(5, N = 605) = 175.09, p < .00].

Non-experimental quantitative studies receive a greater number of relative references and, therefore, achieve greater impact (M=1,42; SD=3.18). Following these come review studies of the literature (M=1,24; SD=1.90), which have considerable impact despite being the most infrequently published type of paper. The studies with least impact are the qualitative ones (M=0,75; SD=0.94) and essays (M=0,76; SD=0.86). It can be seen that the type of study or methodology employed constitutes a determinant factor on its impact [H(5) = 15.78, p < .00]. Table 6 shows the specific types of study where the differences in the impact are significant (p < .05) or highly significant (p < .01).

Table 5. Average and standard deviation from the normalised impact by type of study

|

Type of study / methodology |

Frequency |

Normalised impact |

|

|

Average |

SD |

||

|

Essay |

168 (27.77%) |

0.76 |

0,86 |

|

Quantitative |

159 (26.28%) |

1.42 |

3,18 |

|

Experimental |

135 (22.31%) |

0.84 |

1,06 |

|

Qualitative |

55 (9.09%) |

0.75 |

0,94 |

|

Mixed (quantitative-qualitative) |

48 (7.93%) |

0.93 |

1,83 |

|

Review |

40 (6.61%) |

1.24 |

1,90 |

|

p value (χ2) |

< .00* |

||

|

p value (Kruskal-Wallis) |

< .00* |

||

*Highly significant differences are observed when p < .01.

Source: created by the author

Table 6. Multiple comparatives by the Kruskal-Wallis test on the normalised impact for each of the types of research /

methodologies employed

|

Types / methods compared |

p value (Kruskal-Wallis) |

|

Mixed- Quantitative |

.031* |

|

Qualitative- Quantitative |

.008** |

|

Experiment- Quantitative |

.007** |

|

Essay- Quantitative |

.002** |

*Significant differences are observed when p < .05.

**Highly significant differences are observed when p < .01.

Source: created by the author

Q5. In which countries are most studies carried out? Which accumulate most impact? Is a study’s country of origin a determining variable on its impact?

As might be expected, papers from the English-speaking world make up the bulk of this area, with the vast majority of research coming from United States (US). The four countries with the largest number of studies are English-speaking: US (n=272; 44.95%), United Kingdom (UK) (n=74; 12.23%), Canada (n=34; 5.61%) and Australia (27; 4.46%). Following them we find Germany (n=27; 4.46%) and Spain, with a total of 25 papers (4.13%). Table 7 shows the data from the countries which registered over 10 studies published.

Among the nations with more than 10 studies published, the country with the greatest impact is Italy, with an average of 1.51. Nonetheless, their high value for standard deviation on this variable (SD= 2.56), warns us of the existence of a highly unequal distribution in the number of references, thus Italy publishes some research of great impact but others of much less relevance. After Italy come US (M=1.23; SD=2.56), Canada (M=1.04; SD=1.23), UK (M=0.80; SD=0.99) and Australia (M=0.80; SD=0.64). They are followed by Germany (M=0.75; SD=0,66) and Holland (M=0.73; SD=0.90).

There are notable differences in the number of papers published by country [χ2(47, N = 605) = 5937.99, p < .00]. On the other hand, the country of origin of the studies is not a determining variable on its impact [H(47) = 54.53, p = .21].

Table 7. Average and standard deviation of normalised impact by country

|

Country |

Frequency |

Normalised Impact |

|

|

Average |

SD |

||

|

United States |

272 (44.95%) |

1.23 |

2.56 |

|

United Kingdom |

74 (12.23%) |

0.80 |

0.99 |

|

Canada |

34 (5.61%) |

1.04 |

1.23 |

|

Australia |

27 (4.46%) |

0.80 |

0.64 |

|

Germany |

27 (4.46%) |

0.75 |

0.66 |

|

Spain |

25 (4.13%) |

0.50 |

0.58 |

|

Italy |

18 (2.97%) |

1.51 |

2.56 |

|

China |

12 (1.98%) |

0.44 |

0.22 |

|

Holland |

11 (1.81%) |

0.73 |

0.90 |

|

p value (χ2) |

< .00* |

||

|

p value (Kruskal-Wallis) |

.21** |

||

*Highly significant differences are observed when p < .01.

** Significant differences are observed when p < .05.

Source: created by the author

Q6. Which are the most frequent case studies? Is the carrying out of the case studies a determinant variable of their impact?

A total of 120 case studies were found in our sample, representing 19.83% of the total. Disinformation linked to Covid-19 is the most analysed case (n=26; 21.66%), followed by the 2016 American election (n=15; 12.505), Donald Trump’s mandate in the White House (10.83%) and Russian interference in American politics (n=8; 6.67%). A geographical bias is apparent in the most analysed cases, given that all of them (except the Covid-19 pandemic) are related to political processes linked to US, the leading country in the scientific production in the field of disinformation. The complete data on the frequencies of the case studies analysed is available at the following link: https://cutt.ly/Bb9Ms5d

The case studies have greater impact (M=1.35; SD= 2.01) than the papers that do not include studies of this type (M=0.91; SD=1.91). The nonparametric tests (in this case, Mann-Whitney U as we are only comparing two groups) detect highly significant differences in the normalized impact of both types of study (z = -2.895, p = .004).

Q7. Which types of work and research methodologies are used in the different countries?

Considerable differences can be seen in the types of research published in different countries (table 8). In this section we seek to highlight some of the more noteworthy questions. Firstly, the high percentage of quantitative studies carried out in US (57.35% of research from that nation). 29.41% of research in this country are experimental studies. In general, we can see a greater tendency in the English-speaking countries towards quantitative and experimental research, being 37.82% of studies in UK, 35.29% in Canada and 40.74% in Australia.

It is also worth pointing out the extremely high percentage of non-experimental quantitative research performed in Italy (72.22%). The trend in that country towards the publication of quantitative studies may explain the high average impact of Italian papers; as quantitative studies are those which receive the most references. Over half the studies published in Germany (51.85%) are essays, while Spain is the country with the highest percentage of mixed approach studies (36.00%). In comparative terms, Spain publishes far fewer quantitative studies (only 16.00%, 8.00% of papers are experimental and another 8.00% are non-experimental and quantitative). It is noteworthy that the types of research with greatest impact (quantitative and theoretical reviews) are the least common in Spain.

Table 8. Types of paper by country. Relative frequencies refer to the type of paper published in each country

|

Country |

Quant. |

Qual. |

Exper. |

Mix. |

Rev. |

Essay |

|

United States n=272 |

76 (27.94%) |

15 (5.51%) |

80 (29.41%) |

11 (4.04%) |

14 (5.88%) |

74 (27.20%) |

|

United Kingdom n=74 |

14 (18.91%) |

10 (13.51%) |

14 (18.91%) |

6 (8.11%) |

2 (2.70%) |

28 (37.83%) |

|

Canada n=34 |

9 (26.47%) |

1 (2.94%) |

3 (8.82%) |

3 (8.82%) |

2 (5.88%) |

16 (47.05%) |

|

Australia n=27 |

7 (25.92%) |

5 (18.51%) |

4 (14.81%) |

2 (7.40%) |

1 (3.70%) |

8 (29.63%) |

|

Germany n=27 |

2 (7.40%) |

3 (11.11%) |

6 (22.22%) |

1 (3.70%) |

1 (3.70%) |

14 (51.85%) |

|

Spain n=25 |

2 (8.00%) |

5 (20.00%) |

2 (8.00%) |

9 (36.00%) |

1 (4.00%) |

6 (24.00%) |

|

Italy n=18 |

13 (72.22%) |

1 (5.55%) |

1 (5.55%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (11.11%) |

1 (5.55%) |

|

China n=12 |

7 (58.33%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (8.33%) |

1 (8.33%) |

1 (8.33%) |

2 (16.66%) |

|

Holland n=11 |

1 (9.09%) |

2 (18.18%) |

4 (36.36%) |

1 (9.09%) |

2 (18.18%) |

1 (9.09%) |

Source: created by the author

Q8. What types of work / methodologies are used depending on the topic under study?

Finally, our results indicate that studies about solutions to the question of disinformation generally take on an essay form (33.33% of publications on the topic) and come via experimental methods (25.00%) (table 9). The causes of and the consequences of disinformation and the definitions of key concepts are generally analysed in essays (47.82%; 35.08% and 81.81% respectively). The studies on bias are conducted, fundamentally, with experimental designs (65.54%), while propagation patterns of false content are considered with non-experimental quantitative research (65.96%). Also notable is the percentage of this type of quantitative methodology utilised to analyse the production of disinformation (40.47%).

Table 9. Topics covered by research type. Relative frequencies refer to the topic of each type of research

|

Topic |

Quant. |

Qual. |

Exper. |

Mix. |

Rev. |

Essay |

|

Causes n=46 |

13 (28.26%) |

4 (8.69%) |

1 (2.17%) |

2 (4.34%) |

4 (8.69%) |

22 (47.82%) |

|

Consequences. impact n=57 |

16 (28.07%) |

8 (14.03%) |

7 (12.28%) |

3 (5.26%) |

3 (5.26%) |

20 (35.08%) |

|

Definitions n=22 |

1 (4.54%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (4.54%) |

2 (9.09%) |

18 (81.81%) |

|

Propagation n=47 |

31 (65.95%) |

3 (6.38%) |

6 (12.76%) |

3 (6.38%) |

2 (4.25%) |

2 (4.25%) |

|

Cognitive bias n=119 |

25 (21.01%) |

0 (0.00%) |

78 (65.54%) |

3 (2.52%) |

6 (5.04%) |

7 (5.88%) |

|

Solutions & strategies n=144 |

25 (17.36%) |

15 (10.415%) |

36 (25.00%) |

7 (4.86%) |

13 (9.02%) |

48 (33.33%) |

|

General n=34 |

1 (2.94%) |

1 (2.94%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

6 (17.64%) |

26 (76.47%) |

|

Production n=84 |

34 (40.47%) |

16 (19.04%) |

2 (2.38%) |

21 (25.00%) |

2 (2.38%) |

9 (10.71%) |

|

Perceptions n=22 |

9 (40.90%) |

2 (9.09%) |

4 (18.18%) |

5 (22.72%) |

1 (4.54%) |

1 (4.54%) |

|

Negationism n=5 |

1 (20.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

4 (80.00%) |

|

Role of journalism n=11 |

1 (9.09%) |

6 (54.54%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (9.09%) |

0 (0.00%) |

3 (27.27%) |

|

Emotions n=7 |

1 (14.28%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (14.28%) |

1 (14.28%) |

1 (14.28%) |

3 (42.85%) |

|

Deepfakes n=5 |

1 (20.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

1 (20.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

3 (60.00%) |

|

Cybersecurity n=2 |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0 (0.00%) |

2 (100%) |

Source: created by the author

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study establishes a complete cartography of the subject matter, types of research, areas of knowledge, countries of origin and the impact of the scientific literature on disinformation between 2016 and 2020, so far, the period of greatest attention paid by researchers to this phenomenon. The commonest topics are (1) those that look for solutions to the question and (2) experimental studies into psychological and ideological biases in the reception processes of false content. As for solutions, the studies show a wide variety of focuses over the period observed (a total of 12 different aspects have been found, from which this challenge can be met). The number of studies analysing ways of facing fake news have increased remarkably since 2016. These results show the concern generated by the problem, as well as the emergence of the search for mechanisms to contain it. On the other hand, the studies into cognitive bias, highly prevalent at first, have decreased in number since 2016. This decrease is not an obstacle to placing the field of psychology as one of the areas that generates most papers, confirming previous studies such as that of Ha, Andreu-Pérez and Ray (2019). This research from the field of psychology offers extremely valuable knowledge for analysing the differences in the perception of false content and true information. The bulk of these papers analyse how psychological and ideological biases are activated when citizens tend to believe all that which fits with their worldview (Elías, 2021). These biases also act on the subjects when believing false content, even after having been refuted by fact-checkers (Chan et al., 2017). Processes like backfire effect of fact-checking and motivated reasoning (creating alternative explanations to make reality compatible with ideological bias) have been used to explain resistance to verified information (Cook, Lewandowsky & Ecker, 2017; Swire et al., 2017).

However, none of these aspects -solutions and cognitive bias- are amongst the most referenced. The topic of greatest impact is that focused on the propagation patterns of false content. In this area, the study by Vosoughi, Roy and Aral (2018) is the one that registers the highest number of relative references. The definitions of the key concepts linked to the phenomenon of disinformation is the second category with greatest impact. These definitions are usually dealt with in essays, the most published type of paper. From this last fact it can be inferred that disinformation –in its current form – is a new object of study which still requires the establishment of clear conceptual limits agreed by a scientific community which over the last five years has held incessant discussions about the theoretical underpinning of this phenomenon.

After the field of psychology, political science and the analysis of the social networks are at the forefront in terms of number of papers published. The utilization of misleading strategies in electoral processes and, in general, for political ends, and the importance of digital platforms in these strategies explain these results. The considerable number of papers on health is justified by the avalanche of studies on disinformation which the Covid-19 health crisis has generated since March 2020. The diversity of fields from which the phenomenon has been approached shows its multi-dimensional nature, that has necessitated the collaboration of experts from different disciplines.

Another important aspect is the large number of quantitative papers, especially from the English-speaking world. It would however be preferable to see a greater amount of research using mixed methodology (very little incidence in the studies analysed), whose qualitative perspective could provide greater depth and detail to the statistical results obtained through quantitative methods (Jankowski, 2018). Neither are reviews of the literature particularly common, despite having (after non-experimental quantitative studies) the greatest impact.

From a geographical point of view, our study confirms the leadership of the United States in the study of this question. Previous research had already pointed to the hegemony of US in the scientific and academic approach to false content (Ha, Andreu-Pérez & Ray (2019). In reality, the leadership of the North American country can be extrapolated to the whole English-speaking context (UK, Canada and Australia). Likewise, US provides most of the case studies, focused on the political processes of the American agenda, such as the 2016 election, Donald Trump’s mandate and Russian interference in their politics. This aspect coincides with the results obtained by other studies, such as that of Nieminen and Rapeli (2019).

Calculations made using inferential statistics determine that the type of research (methodological approach) is the only important variable effecting impact. Neither the topic being studied, nor the area of knowledge from which it is approached, nor the country in which it is studied are determining factors.

To finish, it is useful to identify some of the aspects related to disinformation that have not yet received enough attention, and which, therefore, may become lines of research to be explored in future work on this phenomenon. Firstly, there is a noteworthy lack of studies on the legal aspects related to the tagging and elimination of fake news and misleading sources, be they on digital platforms or in other spaces. It is also puzzling that, as opposed to the predominance of research from a political standpoint, the other great motivation behind the generation of false content (economic interest) does not have greater presence in this type of research. It would be interesting to see a strengthening of the approach to such important aspects as black PR –fictitious comments and reviews of products and services available online (Rodríguez-Fernández, 2021)– and, in general, the utilization of disinformation with reputational ends and commercial interests. Neither has there been great prevalence of the study of disinformation in audio formats. The growing importance of audio content in the media environment would make it especially interesting to see an analysis of false content circulating through voice notes on instant messaging services like WhatsApp or Telegram (García-Marín, 2021) or on media such as podcasts, which are increasingly popular. Additionally, it is foreseeable that research into other areas of new technological development, such as deepfakes, or the use of the blockchain as a weapon against disinformation (Tapscott & Tapscott 2016; Dickson, 2017) may acquire heightened importance in coming years.

5. Acknowledgements

This article has been translated into English by Brian O’Halloran.