1. Introduction

Television production has evolved and expanded its possibilities as technology has provided the necessary infrastructure to overcome barriers that until recently were almost unthinkable. Live connections have always been one of the pillars of television, nowadays they are of even greater importance due to the large amount of content available to the public on a large number of platforms. Consumption has become fragmented and viewers, except on special occasions, are no longer captive to channels’ programming and schedules, being able to choose the way they consume content, when, on what platform and which device. Which is why certain programs, such as newsmagazines, use live connections to show viewers that their reporters are on the street, where the news is happening. According to Araceli Infante Castellanos, director of Espejo Público aired on Antena 3, in an in-depth interview carried out by the authors of this paper, nowadays it is not only necessary to comply with the very essence of live TV, which is to be in the places where things happen, but to “establish a certain relationship with the viewer so that they understand that we are on the street. That we don’t just stay on the set” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p.1).

Live connections have evolved alongside technology, and this has also led to an evolution in the narrative. Innovation requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines qualitative and quantitative methods to connect with the needs of users (de Lara et al., 2015).

Traditionally, the infrastructure necessary for its production had been expensive and required complex logistics: a major deployment of technical resources, equipment, budgets and transportation, among other things. Reducing this complexity has been one of the challenges tackled by new technologies that sought to implement a digital system in which a high-quality signal could be sent directly to production control rooms of the different television channels. According to Infante, “When technology works well, it gives you almost everything and that is where the journalist’s criteria come into play to choose what to broadcast and what not to, what to prioritize and what not to” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 1). Technology has improved a great deal it has allowed us to go much further and contact more people.

Over the last ten years, thanks to mobile communication systems, it has been possible to reduce logistical deployment, costs have been lowered, the size of technical teams and human resources have been reduced, compared to sending a signal by satellite and radio frequency. This new technology is embodied in lightweight 3G, 4G and 5G link encoder devices, which can be carried in a small backpack. They are lightweight devices, weighing less than a kilogram, that allow the sending of signals in H264 and H265. The camera is connected to the device via a BNC connector and SDI output, and this sends all the audio and video signal to the control centre. These devices have streamlined the production process without affecting the quality of the broadcast. Satellite technologies have not disappeared and in fact “are increasingly diverse and omnipresent”, (Maniewicz, 2019) but in the case of live television they are used only in specific events, prioritizing the use of mobile connections that speed up production processes.

Television projects based on mobile communication systems allow broadcasting from the indoor set and practically anywhere outdoors, something that with traditional and heavy DSNG equipment -Digital Satellite News Gathering- or mobile units, was not always possible. In addition, these mobile units have an optimal life of just ten years.

A very good example can be found with the greatly reduced infrastructure needed to broadcast races, such as cycling and marathons, where a helicopter is often needed to send the signal. Currently live production over IP allows direct delivery through a standalone camera rig. Systems in turn evolve and outdo themselves. One of the IP-based video streaming companies called LiveU using its proprietary technology of the same name, has released a latest model LiveU800 HEVC which provides multi-camera coverage in a single unit. This system was used for the first time in the Cartier Queen’s Cup 2020 Polo Cup in August 2020 in an event covered by four cameras whose signal was sent from Windsor Park, United Kingdom, to the production studio in South Africa of the Polocam.tv chain. (LiveU, 2020). As with other brands, these devices are commonly called by the name of a representative brand, such as LiveU.

Possibilities offered by live connections from the studio, the capacities and evolution of 3G, 4G systems and the potential of 5G, offer the possibility of launching new and effective challenges in the television landscape.

The advantages of live connections that broadcast the image via mobile signal compared to the DSNG mobile unit are several: cost, size, reduction of equipment, simplification of resources and mobility of the reporter and camera operator. The DSNG is heavier and requires a parking space and location for the unit and permits. Live shows also need to set up in a physical space at the scene of the news. With DSNG you need a cable, and that cable can be accidentally hit by a vehicle, cutting off the broadcast. For Nuria Donate, producer of Espejo Público on the Antena 3 television network, interviewed in depth by the authors of this article, a DSNG “is static and is limited and the reporter cannot stage an impromptu interview or connection, but a mobile system like LiveU -Ip-based video transmission company with technology of the same name- allows the cameraman and reporter to move wherever they want.” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p.1). This system allows immediacy and movement of the editor and operator during the live connection. “Moments such as the release of Iñaki Undangarín from jail or the entry of Luis Bárcenas to prison, could not have been broadcast live if it were not for this system”, explains Nuria Donate (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 1).

The risks or disadvantages of broadcasting with a portable 4G transmission kit in a backpack, can be that the image is pixelated, the signal may fail in basements, for example, or there may be a small delay between the set to the live location. These problems occurred more at the beginning of the use of backpack equipment, when there was only 3G. In the case of Espejo Público the first broadcast of this kind was used in 2011. The delays, pixilation or signal failure all disappeared with the emergence of 5G. Another risk posed by this system can occur with very important news coverage in difficult locations. “Sometimes all backpack services have been rented if not requested in advance” explains Donate (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 4).

Another of its advantages is its greater cost effectiveness, not only because costs have dropped, but because a backpack service can be used for several connections on the same day. On Espejo Público a single service has been used for 3 live connections, which means high-cost effectiveness. Although today satellites are not so expensive and equipment sizes have shrunk, it is a slower process. Lines have to be booked with the corresponding department. They have to be confirmed and others need to be found if they are busy. This signal is always going to be safer than a backpack, but it will depend on the usefulness of that live connection and the type of program. According to the producer of Espejo Público, “If you wanted to do ten live connections, you couldn’t because you don’t have time with DSNG. But with LiveU it is possible. You can start at nine am in Madrid and finish at noon in Toledo” (Santana y Sanz, 2021, p. 2).

1.1. Recording, sending and receiving signal in live connection in Espejo Público

On Espejo Público, usually, the rundown can vary throughout the afternoon and until early the next day and during the program itself. If there are no changes, the next day production contacts the camera operators.

Once the connection has been confirmed, the work process begins with the editor and camera operator going on their own to the location. The production team calls the camera operator one hour before the broadcast to check the quality of image and sound reception. The image and the sound are sent to control and are verified for their output to broadcast. Planning is done an hour in advance to “have time, what they call “air” in case there is a change in the rundown on the fly and if two skypes fail the piece gets bumped up the rundown”, argues Donate (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 4).

In live connections on Espejo Público dynamism is achieved by telling stories and this is achieved by informing and involving the camera operator as well. For the program producer “production and direction have to go hand in hand and in the end that can be seen in the broadcast, if there is a good connection between the two nuclei” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p.3). The live broadcast rundown should specify date, place, subject, needs, type of service, information on the programs and contact information.

Technical needs depend on the type of program or connection you want. Generally, this should include camera, neck microphone and handheld microphone. Also, two mobile telephones, one for the reporter’s communication with the set and another for coordination with the camera operator. On other occasions other needs are specified and elements are added to the equipment, such as LED torches and panels, boom microphone, etc.

Image 1. Camera device and broadcast backpack

Source: Author’s work

1.2. Characteristics of live connections

The technological advances in broadcasting mobile signals have influenced the production of live connections and streamlining, but also the narrative of the discourse. In early television journalism, according to Cebrián (1978, p. 217) live televised connections meant it was possible to broadcast events as they were happening, creating a new space by linking spaces located at a distance and in different places (Cebrián, 1978, p. 217). “Logic made live connection necessary because news had to be covered where the events were occurring” (Mateos, 2013). But today in fact, many connections do not show live action news, because nothing is occurring at that moment, the events having already occurred. According to Infante, “it is about saying, “I am here”, because I am on the street, in a newsworthy location, although it is very relative because basically nothing ever happens” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 1).

Live connections replace the news production process and showcase technological power, something that attracts viewers. Furthermore, if spectacularisation is the use of form and background resources that appeal to emotions and feelings rather than reason (Lozano, 2004), the importance of the image and the greater presence of the reporter are factors that contribute to it when broadcasting live.

Live connections are used by all programs, but especially news and current affairs programs. This includes newscasts and, our case study, the morning newsmagazine Espejo Público. According to Marín (2006, p. 91), “just as the news program is the most representative program of the news and current affairs segment, it can be said that the newsmagazine is the most representative of the entertainment program”.

Live connections take the viewer to where the news is happening. “It is the primacy of the image, of live broadcasts and orality, which give television a sensitive, affective and emotional logic above that of the written media or radio” (González Requena, 2009, p. 14). Before, you could be at an event, film it and broadcast it. “Now this has expanded, and the aim is to broadcast live all the time regardless of how long it lasts,” adds the director of Espejo Público (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 1).

We understand that live connections entail four moments that run in parallel: that of the event, that of narrative, that of the broadcast and that of reception-reading (Cebrián, 1992) or three, according to the categorisation by Concha Mateos (2013): that of the event, that of the enunciation of the story and that of reading. According to Barroso (1996), live connections “takes place when the program signal - television discourse - is broadcast simultaneously to its capture” (p. 40).

Location is another key element, “the reporter is in the place where something has happened, is happening or will happen” (Mayoral et al. 2006 p.250). The location will help structure the discourse and the words are supported by what is seen.

According to Marín (2006, p. 91), “Just as the news program is the most representative program of the news and current affairs segment, it can be said that the newsmagazine is the most representative of the entertainment program.” Espejo Público is a newsmagazine, which contains journalistic genres such as debate, panel discussions, interviews and also news and reportage. Since they are different formats, it is logical that news and live connections should be presented differently in news programs and newsmagazines. The latter is more spectacular, despite its equally informative content. It should be said that Espejo Público began in 1996 as a weekly news reportage program and it was not until 2006 that it became a morning newsmagazine presented by Susana Griso, airing Monday through Friday from 8.55 to 13.30.

2. Objectives

The general objective of the study is to extract the fundamental characteristics of live broadcasts featured on the Antena 3 program, Espejo Público.

This aim then breaks down into the following specific objectives:

- Understanding the fundamental characteristics of live broadcast using a mobile HD signal over the week of July 20 to 24, 2020 on Espejo Público aired by Antenna 3. These characteristics include such things as the duration of the broadcast; transmitter displacement; breaking news; interviews; types of shot; camera movement; composition and type of frame; the type of action being reported on in the live connection and the category of the live connection according to location. They also include mobile HD signals of live broadcasts of up to one minute in duration; between one and two minutes; between two and three minutes and of over three minutes.

- To sum up, the patterns of live connections of the newsmagazine Espejo Público.

3. Methodology

This study uses a two-stage method in which the authors use “both quantitative and qualitative analysis techniques”, in this case “sound or visual […] documents” (De Miguel, 2005, p. 280), which correspond to Espejo Público programs from July 20 to 24, 2020. The first phase of the study is descriptive and is approached using primary qualitative sources in the form of in-depth interviews, as described by De Miguel (2005, p. 253), also called a “semi-standardised” interviews, with the current director of the Espejo Público newsmagazine, Araceli Infante Castellanos, and her producer Nuria Donate. This is added to the author’s professional experience with TV studio technology at different media outlets, as well as secondary newspaper and bibliographic sources. Regarding the professional work of the authors, we have resorted to direct participant observation or global observation “in which the researcher is integrated into the environment of the group studied and intervenes in their daily practices and rituals” (De Miguel, 2005, p. 279).

The second phase of the work is empirical and consists of the detailed study of live connections from 20 to 24 July on Espejo Público through content analysis. Said analysis has been prepared according to the key characteristics mentioned by Infante “the reporter must be able to move around and show their surroundings, if possible, in an outdoors setting that can be easily observed by viewers, giving an overall assessment of the situation, moving around to better outline the story and including an interview if possible” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 1):

With this idea in mind, the following analysis sheet was prepared:

Connection duration: minutes and seconds

Location: indoor or outdoor

Type of emitter: correspondent or reporter

Emitter displacement: Yes or no

Content: topic

Breaking news: Yes or no

Interview: Yes or no

Analysis of the audio-visual image:

- Types of shot

- Camera movement

- Composition and type of framing

- Lighting

- Sound

The nature of the action being covered by the live connection. According to the categorization by Concha Mateos (2013), this is determined by whether it occurs at the time of connection or not and “then the reporter covers something that either has already happened or that they have made happen” (p. 71).

The variables are:

- Live action news: “We are witnessing something that is happening at that moment” (p.71).

- Live connection describing off-camera or past events: “Nothing happens, except our presence as reporters on the scene. It may have happened beforehand (pp.71-72)”.

Live connection category according to where the action takes place as set forth by Concha Mateos (2013, p.73) to which we have added the category of “synchronous live connection”, a term coined by the authors of this study, in which the action continues to occur while the news is being reported live.

- Synchronous live connection. When the action takes place at the same time as the news is broadcast.

- Illustrative live connection. When the action has already occurred, but the location helps to illustrate the news. “It approaches a real live connection: the meaningful action has already occurred but showing the scene of the action is newsworthy at that time” (Mateos, 2013, p. 73).

- Ongoing live connection. When the news has ties to the location, but it is ongoing. Nothing newsworthy is happening at that time (Mateos, 2013, pp. 73-74).

- A supposed event is occurring at the time, we imagine. An unseen newsworthy event is taking place, but it is out of view (Mateos, 2013, p.74).

- Arbitrary live connection. When the connection could have been broadcast from anywhere (Mateos, 2013, p. 74).

- Contrary live connection. When you are in one place, but you talk about action that occurred in other places. (Mateos, 2013, p. 74).

Video only set narration: if the live connection is accompanied by video only voiceover narration or not.

Espejo Público was chosen for this study since it is a good example of a long-lived newsmagazine in Spain - it was aired weekly from 1996 and daily since 2006 - and due to its numerous awards and recognitions. These awards include the National Prize from the Alares Foundation, for preserving work/life balance and social responsibility; the Ondas Television Award to Best Presenter in 2010 (Ondas Awards, 2019), and the Iris Award for the best current affairs program in 2014 (Antena 3, 2020). The sample is of one week’s duration, which means a total of 1,375 minutes of viewing, as daily programs are aired from 08:55 to 13:30.

4. Discussion / Results

On Espejo Público guidelines that are given from the management in terms of content are basic, “that the reporter transmits the news, that they tell the story well and from all points of view and that they talk with the guests so that they know that time is limited and that they have to be specific in the message” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 3). Regarding audiovisual language, the guidelines are that the reporter should move around, be outside and easily locatable in terms of settings, that they give the fullest picture possible of what is happening, the live connection should be leveraged as much as possible.

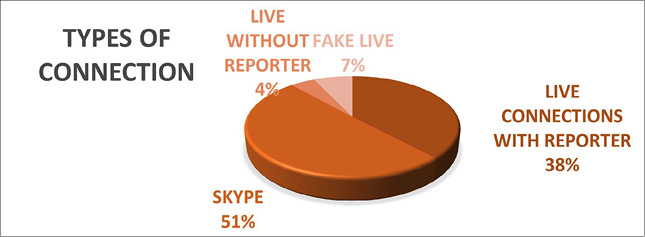

4.1. Types of connections

Of all the live connections on Espejo Público from 20 to 24 July, this study focuses on those in which we see a reporter and camera operator with a giving a live account, whether or not there are ‘live’ or ‘breaking news’ tickers on screen. Our analysis focuses on how images and accounts reach viewers. Therefore, the connections in which the reporter does not appear have not been used and fake live connections where a lead in simulates a live broadcast but is followed by an edited VTR have also been discarded. This study focuses on live connections, their narrative, staging and significance in the discourse. In total, we analysed 44 live connections, and we discarded five connections without a reporter and eight fake live ones. Video calls using Skype have not been studied either (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 4), since they do not belong to the object of our study.

Figure 1. Types of connections

Source: Author’s work

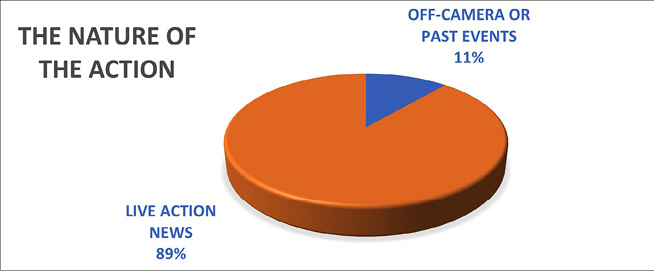

4.2. The nature of the action being covered by the live connection

Most connections according to the nature of the action are live action news stories, 39 overall. These live connections comply perfectly with what was set forth by Mateos (2013), since in these cases the viewer witnesses something that is happening at that very moment. “That is the essence or purest type of the live connection” (p.71). On the contrary, only nine live connections cover events off-camera or happening in the past.

Figure 2. The nature of the action

Source: Author’s work

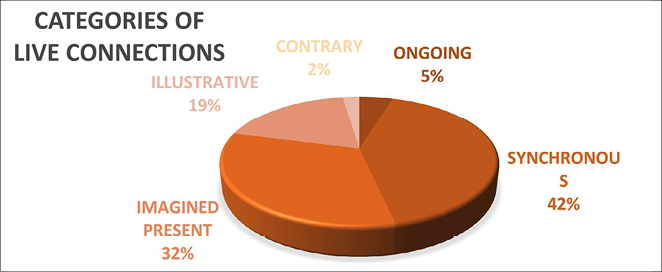

4.3. Category of live connection according to the location of the news being reported on

In this category we analyse whether the location where the action takes place is related to the news or not. The most common live connection is that of the ‘synchronous’ connection, with 18 cases, where the action occurs at the very moment the news is captured and broadcast and lasts for the entire time. Among live action news reports, the “synchronous live connection” is the purest. Some of the scenarios of the 18 live connections include the protests by medical students; protests by bullfighters and gym owners; a sports hall used for emergency PCRs; inside a school with the new Covid signage for the beginning of the school year; the inside of a chemists in Andalusia where free masks were handed out to the elderly; the stalls at the yearly book fair in Madrid; the place in Aguilar where a real-time excavation is being carried out to search for the body of Ángeles Zurera, or inside Terminal 4 of Adolfo Suárez airport where the reporter talks about new safety checks.

The “synchronous live connection” is followed by imagined or assumed present, (Mateos, 2013, p. 71-72) in which something is happening, but we cannot see it, such is the news that occurs inside the hotel where the Fuenlabrada players are quarantined due to Covid, while the reporter broadcasts from outside the hotel; or the imagined present where an assaulted minor is admitted to the La Princesa hospital in Madrid, while the reporter interviews her mother outside the hospital. According to the categorization by Mateos (2013), these were followed by eight illustrative live connections and two ongoing live connections. In the illustrative live connections, the action has already occurred, but the location is still newsworthy, such as the case outside the Santomera prison, in Murcia, where a man convicted of murdering his parents is being released or outside of a burned shop in Torrox. Undoubtedly the reporter did not capture the moment of the fire, but the burned shop and the remains of the tragedy illustrate what happened. In the ongoing live connection, there is a relationship with the location, but it is invariable. Nothing is happening in the place where the connection takes place, such as was the case of the outbreaks of covid at the end of term party in Córdoba. In this case we see the reporter on the outside landing of a building that, although it could be a Security building, does not have any signage, so it could be any building on any street. The other ongoing live connection is a report in the news about the European Union Summit and the subsidies to Spain. On this occasion, the correspondent is in a city street in Brussels with the background of what could be an emblematic building of the EU but is not easily identifiable. For this reason, we consider that if the viewer cannot appreciate that they are in front of an EU building, the place is no longer illustrative, but an ongoing live location. Only the connection in Gandia does not comply with this categorisation because the live connection takes place in one place and refers to actions that occurred in other settings.

Figure 3. Live Connection Categories

Source: Author’s work

4.4. Breaking news live connections

Of the live connections analysed, there is a high percentage of “breaking news” connections, a total of eighteen out of forty-four. All are live action news stories in terms of the nature of the story, except one: a news item, reported on by a prominent correspondent in Brussels in front of the European Parliament and reports on the Covid aid package concluded the previous morning. In this case, the live connection does not show the action directly since nothing happens, other than the correspondent being at the location even though the event took place before.

These “breaking news” connections are characterised by maintaining the original essence of the live connection from the location where events took place. Therefore, the news is narrated from the location, whether it be a demonstration of by junior doctors at the headquarters of the General Directorate of Human Resources of SERMAS, a pavilion where PCRs are being done in Santa Pola, a protest by gym and sport centres owners against their closure, or a demonstration by bullfighters in front of the Ministry of Labour.

Despite being live action news stories, the category of live connections depending on location is varied. There are eight live connections that take place in an imagined present, another eight that are “synchronous”, and only one ongoing and one illustrative live connection. Combining live action news and “synchronous live connection” is the live formula par excellence: we are witnessing something that is happening at that very moment and also the action occurs at the moment of capture and broadcasting of the news. Since they all are live action news stories, there are no arbitrary live connections, where nothing happens except that the reporter is at the scene.

Figure 4. Breaking news live connections

Source: Author’s work

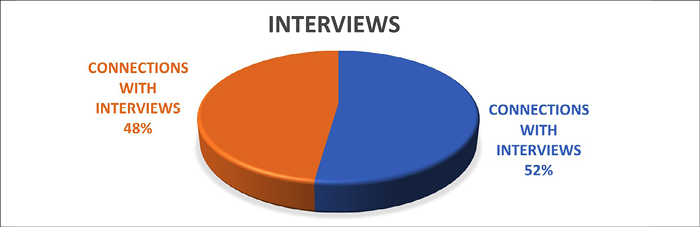

4.5. Connections including interviews

The live interview provides first-hand information from a protagonist of the news. These occur in a high proportion, 21 out of 44 live connections. As for the dynamics of the interview, in all cases it is the same. It begins with a medium-long or general shot with a reporter and interviewee moving to a medium close up of the interviewee answering. Then the cameraman takes the reporter’s position, leaving them foreshortened or only leaving the mic in shot. When a new question is asked, the shot is sometimes reframed to include the reporter. At the end of the interview, the reporter is reframed for his to give a sign off, panning out from the interviewee.

Figure 5. Connections including interviews

Source: Author’s work

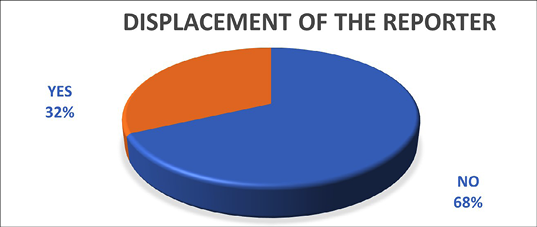

4.6. Reporter displacement

The displacement of the reporter during the connections is one of the factors that support Araceli Infante’s thesis on the importance of the program being able to say it is ‘at the scene’ (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p.1). It seeks to broadcast the moment, but also these displacements give the audience something to watch when there is no action per se. In the fourteen displacements, the news is reported on live, while it is happening. Of these, in the category of the connection according to the location of the news being reported on, there are a total of eight “synchronous live connections”, and these are the most common. This is followed by imagined present and illustrative live connections, with a total of two each. On the other hand, arbitrary live connections and contrary connections make up just one each.

Figure 6. Connections with or without reporter displacement

Source: Author’s work

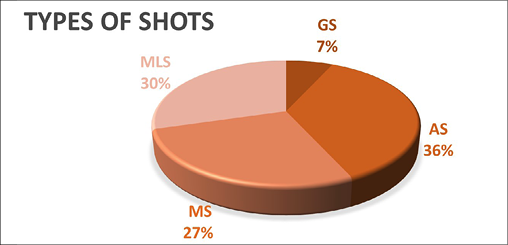

4.7. Types of shots

The majority of shots are American shots (AS), 16; medium-long shots (MLS), 12; medium shot (MS), 13; and general shots (GS), three. The use of a type of shot during the course of the news piece is counted once, not the number of times the shot is used. American shots, showing the main protagonist and their surroundings, appropriate when there is significant movement around the scene, appears in three live connections. American shots that show the reporter from the head to knees is widely used. It is fact that medium shots, normal sized and in the broadest terms version, account for almost all the shots used, a total of 57% and appearing in 25 live connections.

We have not included sequence shots in the selection of shots since it requires different shot sizes and camera movements. In the whole study there is only one sequence shot, appearing on 21 July, which lasts 1 minute and 45 seconds. This sequence shot shares characteristics of a fully live connection, given a spectacular sheen. It begins with a sequence shot of the reporter at the entrance of a school. A tracking shot with the reporter walking backwards as she enters the premises and stops where the head of the school is waiting to be interviewed. At the end of the interview there is a side-on tracking shot following the reporter as she moves to her right and the school head moves out of the shot. This is followed by tilt down for a close up of the signage on the ground, a tilt up and the tracking shot continues, with a second tilt down a close up of the reporter’s back climbing the stairs. In this case the camera takes a low angle shot from below. This is followed by a travelling in shot of the reporter entering a classroom. Inside, the camera takes several side-to-side and up and down panoramic shots to illustrate the classrooms dimensions. The camera tilts up and the shot is reframed with the reporter in an American shot to sign off the live connection. This example of a pure live connection, according to the nature of the action, a live news report, and according to the scene of the action it is a “synchronous live connection”. This is one of the examples in which video only voiceover images are not possible since everything is being shown in real time.

Figure 7. Types of shots

Source: Author’s work

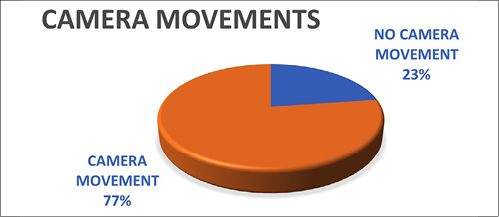

4.8. Camera movements

According to Millerson (2008), if we do not guide the eye through the scene, it will tend to wander through the image. In this sense, camera movements simulate what the human eye would see if it were on the scene.

Of the 44 live connections studied, only nine do not include camera movements. One of them is on a road near the Santomera prison, another in front of the façade of the European Parliament, another in front of the Eibar Police Station, another outside the Durango Court House and one inside Aranau Hospital in Villanova. In all these cases the location does not allow for movement and the importance of the news is to show that particular location where the events are happening or have happened. There is a majority of live connections with camera movements, accounting for 35 total cases.

Next, we will mention the most common camera movements, counting only their appearance in the live connections and not their successive appearances within it. Among the most common movements is the in and out tracking shots, circular and lateral tracking; left to right and up and down panoramic and panning shots and zooming in and out.

Of the 44 live connections analysed, the movement that appears mostly is the tracking shot, where camera and the support move together. In these cases, the support is the camera operator himself with a hand-held camera. The majority of tracking shots are tracking out shots, appearing in a total of 24 live connections. There are eight tracking in shots, seven side-on tracking shots and 2 circular tracking shots. As for panning shots, in which the camera moves on a support that remains fixed, right to left panning shots appear in 27 live connections, while panning up and down appear in a total of four. The camera zooms in and zooms out in nine and ten live connections respectively.

Types of tracking shots are usually combined in the same live connections with panning shots to different effect. The most common case is the walk and talk tracking shot out with the reporter moving towards the camera as they recount the news and a slight zoom in that serves to reframe and go from an American shot to a medium to long shot or medium shot. Sometimes the journalist’s walk and talk lasts the entire live connection and in others it is combined with other types of tracking shot. In terms of combinations, there are walk and talk tracking shots to a final stopping point from where, retrospectively and in another direction, the reporter walks backwards and the camera operator follows them. This choreography is the most common. Sometimes a side-on or circular tracking shot is added. At other times side-on or circular tracking shots are added to the walk and talks. The circular tracking shot is used to pan from the reporter to scene of the news and end up at the reporter with an interviewee again. Panning shots appear frequently following the reporter’s lead in or at any time during the connection to show part of the scene and even zooming in to some details. There are live connections in which only panoramic appear and others that combine panoramic with tracking shots. Zoom ins are often used in tracking shots to get closer to the reporter or interviewee, or to see some detail. The zoom outs enable the camera to go from an American shot to a medium to long shot or medium shot.

Figure 8. Camera movements

Source: Author’s work

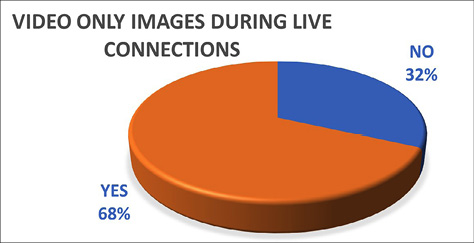

4.9. Video only voiceover images during live connections

Video only voiceover images in Espejo Público are of great importance. They are intended to be illustrative, the program uses video only voiceover images as much as possible in its production. When this does not happen, it is because the event is happening live and no images with voiceover to go with it, or because the event is so important that it should cover the screen as much as possible. In fact, when the image “is very good, it goes to full screen with a sign that helps the viewer to get hooked,” explains Infante (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 5).

Thirty live connections have video only voiceover images compared to 14 without. The video only voiceover images run from the start of the news piece or enter later. The most common ‘hook’ was a screen divided in two with the left half with the reporter and / or interviewee in a quarter of the screen and video only voiceover images on the right-hand quarter. When the presenter or collaborators intervene from the set, they go to split screen and then split the screen in four for the answers. The screen can be divided into up to five parts. These divisions alternate throughout the live connections.

Connections without video only voiceover images are illustrated with live images and have more camera movement, mostly scene-setting panoramic and tracking shots. Sometimes when there is an interview, the video only voiceover images are dropped when the reporter asks a question.

Figure 9. Connections including video only voiceover images

Source: Author’s work

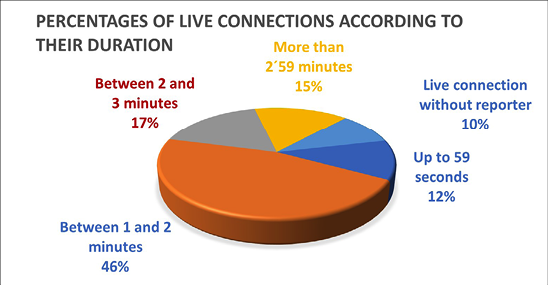

4.10. Characteristics of live connections according to their duration

The 44 connections studied have been divided according to their duration, the most numerous being those of between one and two minutes, with 22 live connections. They are followed by those of between two and three minutes with nine connections and then those of over three minutes with seven live connections. The last place is occupied by those of less than one minute with six live connections.

Figure 10. Live connections according to their duration

Source: Author’s work

4.11. Live connections of up to one minute

Of the live connections of less than one minute, the shortest lasts 46 seconds and the longest lasts 58 seconds. It should be noted that four of them are “breaking news” and that all are live action news reports. In half of them the reporter moves around and in all there is camera movement. All types of shot sizes are used. There are three synchronous lives connections, three imagined presents and one ongoing live connection.

4.12. Live connections of between one and two minutes

Live connections of between one and two minutes occur the most in this study, a total of 22 times. The shortest lasts 62 seconds and the longest 1 minute and 59 seconds. Only six of them are “breaking news” connections. During 16 of these live connections the reporter did not move around the scene. All but two are live action news reports. The camera moves around in 14 of these live connections. All types of shot sizes are used. According to the action occurring during the live connection there are nine “synchronous live connections”, six where the present is imagined, one arbitrary live connection and five illustrative live connections.

4.13. Live connections of between two and three minutes

Live connections of between one and two minutes are the second most numerous in the study. The shortest lasts two minutes and six seconds and the longest 2 minutes and 46 seconds. There are three “breaking news” connections. In seven of them the reporter does not move around. There is camera movement in seven of them compared to two where there is none. All types of shot sizes are used. All but two are live action news reports. According to the action occurring during the live connection there are two “synchronous live connections”, three where the present is imagined, one ongoing live connection and two illustrative live connections.

4.14. Live connections of over three minutes

This section requires special attention since the essence of live connections mean these are shorter. In this section, live connections that exceed three minutes range from 3 minutes and 20 seconds to 11 minutes and 46. There are two connections between three and four minutes, three connections between four and five minutes, and two between 10 and 12 minutes. What justifies such a long duration are three characteristics common to all: they feature interviews with people who are pertinent to the story taking up at least part of the live connection, all are newsworthy, allowing for the story to be told and giving live testimonies from the scene and allowing intervention from the set. These three characteristics define long-term live connections and justify it.

In all these live connections there are video only voiceover images that illustrate and complement them, except for the live connection at the gym owner protest in Catalonia. In this case, the images that the viewer needs to see are those of the demonstration that is taking place in real time and therefore no video only voiceover images are needed.

All of them carry an interview with a protagonist of the news and connect with the set from where they ask new questions and make comments. In the case of 22 July in the three live connections, the interview is the central axis. In the first, they interview the mother of a girl attacked at the doors of the hospital where she is admitted (9’31”). In the second case, they interview a gym owner before the closure of these due to outbreaks of Covid in Catalonia, while the demonstration is taking place (4’49”). And thirdly, a bullfighting impresario is interviewed in front of the protest that is taking place at that very moment at the gates of the Ministry of Labour in Madrid (11’46”). On 22 July, the live connections also carry an interview. In the first live connection, a reporter interviews a client of the NH hotel where the players of the Fuenlabrada soccer team are self-isolating. On the following day (10’), a member of a Casa de Campo neighbourhood association was interviewed to talk about the crime in the area due to young immigrants. The live connection of over three minutes on 23 July (4’4”), also carries an interview with one of the Lleida business owners who are protesting the closure of their businesses. On 24 July there are two live connections over three minutes. The first (4’40”) is with two representatives of youth associations in Mendillori who complain about being criminalized since they are held responsible for the increase in Covid cases. The second (3’35 ”) is a testimony by Dr. Morales, responsible for the Covid wards at the Arnau de Villanova Hospital in Lleida.

These live connections do not involve displacement of the reporter when the interview lasts for the entire connection. They do entail displacement when the reporter walks around the scene before going to meet the interviewee. Only in those cases are there in, out and circular tracking shots. In all of them the camera pans left and right to reframe for the answer or for a new question.

Despite the fact that the nature of the action that the live connection is covering is live action news: “We are witnessing something that is happening at that moment”, the category of the live show varies according to the scene. There are only three “synchronous live connections” in which the action is taking place and covering all the news content. The rest are three live connections that are: an imagined present and two illustrative live connections.

Table 1. Results of daily analysis of live connections

|

IMAGE ANALYSIS |

||||||||||||||

|

<59¨ |

P |

LENGTH |

L |

TE |

BN |

IN |

DE |

TS |

CM |

S |

LI |

NA |

CASA |

VO |

|

20 |

N1. LC1. 48¨ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

N13. LC7. 46¨ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

NO |

||

|

21 |

N2. LC2. 58¨ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

|

|

22 |

NONE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

N3. LC3. 55¨ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

GS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

N6. LC3. 57¨ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

24 |

N2. LC2. 53¨ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

YES |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

|

|

1-2´ |

P |

LENGTH |

L |

TE |

BN |

IN |

DE |

TS |

CM |

S |

LI |

NA |

CASA |

CL |

|

20 |

N2. LC2. 1.02´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

YES |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

ARB |

YES |

|

|

N3. LC3. 1.07´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

YES |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

||

|

N10. LC5. 1.18´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

YES |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

WITH: |

NO |

||

|

N11. LC6. 1.56´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

NO |

GS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

N18. LC8. 1.19´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

NO |

MS |

NO |

D |

N |

VII |

ILU |

YES |

||

|

21 |

N1. LC1. 1.12´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

NO |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

|

|

N4. LC4. 1.29´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MS |

NO |

D |

N |

VII |

ILU |

YES |

||

|

N7. LC5. 1.48´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

N14. LC8. 1.02´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

ILU |

YES |

||

|

N23. LC12. 1.45´ |

E / I |

R |

NO |

YES |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

22 |

N1. LC1. 1.08´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

MLS |

NO |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

N11. LC5. 1.22´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MLS |

NO |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

|

N19. LC7. 1.58´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

23 |

N1. LC1. 1.43´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MLS |

NO |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

N3. LC2. 1.16´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

|

N10 LC4. 1.14´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

VII |

ILU |

YES |

||

|

N12. LC5. 1.49´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

ILU |

YES |

||

|

N13. LC6. 1.59´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

||

|

N15. LC8. 1.04´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

NO |

AS |

NO |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

|

24 |

N1. LC1. 1.07´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

|

|

N7. LC3. 1.53´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

N21. LC.10. 1.15´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

NO |

MS |

NO |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

|

2-3´ |

P |

LENGHT |

L |

TE |

BN |

EN |

DE |

TS |

CM |

S |

LI |

NA |

CASA |

CL |

|

20 |

N8. LC4. 2.06´ |

E |

R |

NO |

NO |

NO |

MS |

NO |

D |

N |

VII |

PER |

YES |

|

|

21 |

N11. LC6. 2.22´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

N13. LC7. 2.08´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

|

22 |

N2. LC2. 2.15´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

NO |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

23 |

N18. LC10. 2.41´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

|

|

24 |

N8 LC4. 2.21´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

|

|

N16. LC7. 2.11´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

VII |

ILU |

NO |

||

|

N19. LC8. 1.59´ |

E |

R |

YES |

NO |

NO |

MS |

NO |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

||

|

N24. LC12. 2.22´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

YES |

GS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

ILU |

YES |

||

|

>3´ |

P |

LENGTH |

L |

TE |

BN |

EN |

DE |

TS |

CM |

S |

LI |

NA |

CASA |

CL |

|

20 |

NONE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

N17. LC9. 4.49´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

YES |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

|

|

N18. LC10. 11.46´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

YES |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

NO |

||

|

22 |

N10. LC4. 3.20´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

NO |

MLS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

SYN |

YES |

|

|

N16 LC6. 10´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

|

23 |

N14. LC7. 4.04´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

YES |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

|

|

24 |

N20. LC9. 4.15´ |

E |

R |

NO |

YES |

NO |

AS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

ILU |

YES |

|

|

N23. LC11. 3.35´ |

E |

R |

YES |

YES |

NO |

MS |

YES |

D |

N |

LAN |

IP |

YES |

||

Source: Author’s work

Table 2. Table key

|

KEY: |

|||||||||||||||

|

P: PROGRAM |

R: REPORTER |

||||||||||||||

|

N: NUMBER OF THE NEW AND LC: NUMBER OF LIVE CONNECTION |

GS GENERAL SHOT |

||||||||||||||

|

L: LOCATION |

AS: AMERICAN SHOT |

||||||||||||||

|

TE: TYPE OF EMITTER |

MLS: MEDIUM LONG SHOTS |

||||||||||||||

|

BN: BREAKING NEWS |

MS: MEDIUM SHOT |

||||||||||||||

|

IN: INTERVIEW |

L: LIVE |

||||||||||||||

|

EM: EMITTER MOVEMENT |

N: NATURAL |

||||||||||||||

|

TS: TYPE OF SHOT |

LAN: LIVE ACTION NEWS |

||||||||||||||

|

CM: CAMERA MOVEMENTS |

OFFCAM: OFF-CAMERA OR IN THE PAST |

||||||||||||||

|

S: SOUND |

SYN: SYNCHRONOUS |

||||||||||||||

|

LI LIGHTING |

IP: IMAGINE OR ASSUMED PRESENT |

||||||||||||||

|

NA: NATURE OF THE ACTION |

ILLU: ILLUSTRATIVE |

||||||||||||||

|

CASA CATEGORY ACCORDING TO THE SCENE OF THE ACTION |

ON: ONGOING |

||||||||||||||

|

VO: VIDEO ONLY |

CONTR: CONTRARY |

||||||||||||||

|

O / I: OUTDOORS / INDOORS |

ARB: ARBITRARY |

||||||||||||||

Source: Author’s work

5. Conclusions

The use of mobile signal image delivery technology is more operational than the use of DSNG.

The live connections on the newsmagazine Espejo Público mostly comply with the guidelines set by the program’s production team: they narrate the story well and from all points of view, talking with the protagonist of the news and asking them to be specific. Furthermore, in terms of audiovisual language “that the reporter moves around, trying the show their location outside, giving the most complete picture possible, moving around more and better explaining the story” (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p.3).

Live action news reports represent the majority of the connections, a total of 89%.

In the category that analyses the scene where the live action takes place, the most used, 43%, is the “synchronous live connection”, in which the action occurs at the same time the news is captured and broadcast and lasts the entire time. It is followed by the imagine present, in which something is happening, but we cannot see it, in 33% of cases; the illustrative live connection in which the action has already happened, but the place is still relevant, in 19% of cases; the ongoing live connection where the relationship with the place is invariable, in 5% of cases; and the contrary live connection, which speaks of actions that occurred in other places, with 2% of cases.

The combination of live action news reports and a “synchronous” live connection is the ideal and purest form of live connection. The combination of connections that report on the action when it has already taken place or is off-camera and arbitrary live connections are of the least value.

Of the live connections analysed, there are a high percentage of “breaking news” connections, 41% of cases and all of them are live action news reports, except one. These are characterised by maintaining the original essence of the live broadcast from the same place of the events. Despite being live action news reports, the category of live connections depending on location is varied.

The live interview is a hallmark of the news and offers the testimony of a protagonist. Interviews are filmed ensuring that the interviewee takes centre stage, not the reporter. For this, the camera takes the place of the reporter who is foreshortened or disappears from the frame. When questions are asked, the camera does not always reframe, and question may be asked off camera. At the end of the interview, the reporter is re-framed to give a sign off, panning out from the interviewee.

How spectacular the live connection is determined more by the camera movement than by the movement of the reporter. The reporter moving around occurs in 32% of cases and therefore is less significant than camera movement, seen in 77% of cases. Movement of reporters during live connections bolsters Infante’s thesis (2020, p. 1) in which live connections must make clear that the news is being reported on from the street and not just from the set. In addition, this movement makes up for the lack of action.

We see all types of camera shots in live connections, although the majority are medium shots, both medium and medium-long shots. These represent 57% of the total. These are followed by the American shot, accounting for 36% cases and general shots, totalling 7%. Sequence shots are also used on occasion.

Camera movement using a combination of tracking shots and panoramic shots give the news a sense of spectacularity. The majority of live connection feature some kind of camera movement, accounting for harm 77% total cases studied. All types of camera movements are used in live connections: In and out and circular tracking shots, panoramic or left to right and up and down panning shots; and zooming in and out.

Of the 44 live connections studied, the most commonly used camera movement is the tracking shot. The majority of tracking shots are tracking out shots, appearing in a total of 24 live connections. There are eight tracking in shots, seven side-on tracking shots and 12 circular tracking shots. As for panning shots, left to right panning shots appear in 27 connections, while up and down panning shots in four. The camera zooms in and zooms out in nine and ten live connections respectively. Combing these camera movements is common in live connections. The most common case is a tracking shot with the camera walking towards the subject and slight zooming in from American shots to medium to long shot or medium shot. The tracking shot out followed by tracking shot in with reporter walking backwards is also common. Sometimes a side-on or circular tracking shot is added. The circular tracking shot is used to pan from the reporter to the scene and ends up at the reporter with an interviewee again. Panning shots always show a relevant part of the scene. Zooming in and out on the reporter or the interviewee or showing some detail of the news or going from American shots to medium to long or medium shots is also common.

A total of 68% of live connections on Espejo Público feature video only voiceover images that illustrate the news. When they do not appear, it is either because there is no available video only voiceover images or because the news is so important that it should cover the screen as much as possible. They can be used at the start of the news piece or later. Connections without video only voiceover images are illustrated with live images and have more camera movement. In these cases, there are many panoramic scene-setting and tracking shots. The most common ‘hook’ is a screen divided in two with the left half with the reporter and / or interviewee in a quarter of the screen and video only voiceover images on the right-hand quarter or the other half with the presenter or collaborators from the set. “Synchronous” live connections and live news reporting usually do not feature video only voiceover images because the action is filmed live.

News reporters are journalists, while newsmagazine reporters are narrators who seek to present a testimony of what is occurring. “Backpacks are essential to tell these stories”, concludes Donate (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 7).

The most common live connections in Espejo Público are of between one and two minutes, 46% of the total. They are followed by those of between two and three minutes, making up 17% of cases, and are immediately followed by those of over three minutes, 15% of cases, and lastly those of less than one minute, accounting for 12% of cases.

Live connections of over three minutes have three common characteristics that justify them: they carry an interview with a protagonist of an element of the news, they feature interventions from the set, and they are live action news stories. These live connections do not involve displacement of the reporter when the interview lasts for the entire connection.

The future of general television is to offer live news across all formats and platforms. Being on the street, telling the story from there, and less from the set, will be the future of news programs, in addition to countering misinformation and fake news. According to Donate fact checking and street level reporting are what viewers are demanding (Santana and Sanz, 2021, p. 6).

6. Acknowledgements

This article has been translated into English by Gorka Hodson Otaola.