1. Introduction

In democratic societies, the growth of information transparency is framed as a key issue for the development of citizenship and the political role of the State administrative apparatus and other social institutions.1 On the one hand, information transparency and democratic participation has a legitimizing effect for political systems and, on the other, the Information Society itself, the largest depository of knowledge and horizontal communication ever known. Based on a social perspective and using empirical results from a qualitative study,2 this paper examines the importance of social media communication for the production of information transparency, paying special attention to the active role (participative) of citizens in this communicative process.3

From this perspective, the idea of information transparency as little more than a response by a public or private organization to legal obligations is dispensed with. On the contrary, the communicative dimension is central to the phenomenon of transparency, in particular the importance of reception, which has repercussions in mass communication media and most especially in online social media and communities.

Specifically, this study explores distinct types of transparency as related to citizen participation, with the aim of exploring and critically assessing the generic idea that increased access to information leads to more effective transparency and its endorsement by citizens (Unsworth & Townes, 2012; McDermott, 2010). From the point of view of this research, such supposed accessibility should be completed and even incorporate the possibility of ‘inaccessible’ information as an aspect of efforts to produce the desired transparency.4

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodological Approach

From a theoretical perspective, and speaking generally, information transparency is commonly thought to be determined by the sender, who unilaterally produces and manages the process by which information is transmitted or communicated to others (real or potential). This is understood as being an automatic and efficient process and guaranteed by correspondence between sender and receiver. It is in this sense that the link between transparency and institutional openness to the public can be understood. According to the Anti-Corruption Plain Language Guide, published by the NGO Transparency International (2009), transparency is defined as:

Characteristic of governments, companies, organizations and individuals of being open in the clear disclosure of information, rules, plans, processes and actions. As a principle, public officials, civil servants, the managers and directors of companies and organizations, and board trustees have a duty to act visibly, predictably and understandably to promote participation and accountability (p. 44).

In various reports and recommendations, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) takes a similar view. It defines transparency as the space in which policy objectives, their framework, the rationale for policy decisions, data and information related to the economic underpinnings of policies are provided to the public in an understandable, accessible and timely manner.

However, this broad standards and procedures based proposal, which sees communication as an uninterrupted and error free process, is not free of distortions and impediments. In fact, it tends to exclude the importance of comprehension and interpretation that, by default, influences all acts of communication. In other words, from the perspective of human communication, the reception of information is a separate and independent dimension from the sender. Based on this purported lack of correspondence, the main objective of the analysis presented in this work was to test this distinction (separation) between sender and receiver transparency.

In relation to sender transparency, numerous empirical and theoretical studies treat information as a product to be displayed. Little or no interest is expressed in specifying the role of reception (receiver transparency), which is considered to be superfluous as the receiver is assumed to only transmit relevant information.

Simmel’s (1906) sociology of secrecy addresses the idea of a difference between what is known about people and what is actually communicated. It posits the privilege of the sender and the information they hold and how this may prejudice the receiver who must rely on other senders and their willingness to share information. Bentham’s (1979) work on the panopticon, reapplied in diverse forms by authors such as Foucault (1986), Vattimo (1989), Wajcman (2010) and Byung-Chul Han (2014), is also relevant. Here, the ‘sender’ determines what is seen, meaning that the possibility of concealment is a central and prior issue in any communicative event. As such, it affects that which is in plain sight long before it is exposed to the complexity of a watchful and scrutinizing eye.

In summary, sender transparency permits the eye to ‘see’ but not to ‘look’. Which is to say, opacity is created in the very moment of exposure when the sender does not take into account the intentionality of the scrutinizing gaze of a receiver.5 Although it arises out of a desire to avoid concealment, said opacity acts to rule out any overt surveillance at reception. If sender transparency avoids the concealment of information by making it visible (generating supervision), receiver transparency denounces it for curtailing the possibility of looking beyond what has been shown and made visible.

Applying Simmelian theory to the aforementioned concepts, secret and disclosed information can be understood as two sides of the same coin. That which is not secret is revealed and, therefore, automatically manifest or unveiled. As such, in information transparency there is, inevitably, a closely related positive and negative side.6 The positive aspect is egalitarian because the emphasis is placed on convergence, where sender and receiver share information. Conversely, the negative side is divergent by way of the differentiating effect of concealment (opacity) over disclosed information. However, as both types of transparency are in reality interdependent, egalitarian transparency can only be said to aim for a ‘minimum’ divergence between disclosed (sent) and received information. In other words, the greater the degree of transparency (exposition), the less the receiver can ‘look’ (inform themselves), until eventually we reach the paradoxical situation where transparency equates to ‘invisibility’ and the very concealment that said transparency seeks to avoid.

Hence, the theoretical framework for the analysis formulates an understanding of the reception of information where, for various reasons (poor vision, lack of knowledge amongst receivers of the appropriate codes, lack of clarity in messages, or confusion between communication channels, etc.), no effective demonstration of its existence is apparent to receivers. On this basis, the analysis presented in the following section, seeks to explore the relevance of ‘negative transparency’ produced by the existence of information that the receiver has no access to, except for that which the sender withholds (or the suspicion thereof).

Such a proposal is implicit in the notion of the ‘gaze’ formulated by Lacan (1964) and in the premises of visual phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, 1986), which makes a clear distinction between ‘seeing’ and ‘looking at’ the world that surrounds us. Very briefly, under these theoretical suppositions, the ‘gaze’ is not a point of meeting or correspondence between what is visible to (shown) and seen by the subject. In reality, it is quite the opposite. The gaze originates in the ‘stain’ that impedes the transparency of the image. In this sense, Žižek (2000), referring to cinema, highlights the lack of intention of the camera when it shows what we see, as we only glimpse fragments of a whole that is supposedly evident and complete. However, what is not evident is that which arouses the desire to see and potentiates the audience’s (receivers) gaze. In the same way, all acts of transparency are necessarily contrived and incomplete exercises in the display of information to citizens. But, by attempting to make such information visible, the reception of information comes into play: it elicits a certain passive attitude in the receiver or, on the contrary, it becomes a motivation for participation in the communicative act through efforts to complete the information that was falsely presented as whole.

On the basis of this theoretical approach, the research explores to what degree citizens understand acts of information dissemination on social media by public and private Spanish organizations within a frame of transparency. To do this, three discussion (focus) groups were carried out with frequent social media users. This qualitative method was chosen for its appropriateness as a technique for exploring ideological frameworks. In particular, spontaneous discussion of the relationship between digital social media activity by organizations and information transparency, rather than through closed, prompt-based research methods. Three discussion groups with the following characteristics were designed:7

Group 1. Young people aged 25 to 30 years, from middle and middle-upper class backgrounds, with a university education. At least half the group were working in private sector companies in professional-technical jobs (identified as RG1 in the text).

Group 2. Men aged 30 to 40 years, from middle-class backgrounds and employed in the service sector (finance, insurance, sales, etc.). (RG2)

Group 3. Women aged 30 to 40 years, from working class backgrounds, of which at least half were employed in commercial and administrative jobs. (RG3)

All three groups took place in Madrid in 2017. Within the logic of qualitative research and the practice of discussion groups, which is based on openness and non-directivity, the discussions were based on the following themes:

- Habitual use of digital social media: motivations, resistances, grounds for discussion, etc.

- Activities that participants may have stopped doing or did less of that was attributable to social media use. Of particular interest was any relationship with less frequent engagement with traditional communication media.

- Non-personal social media accounts that the participants followed; reasons for following them.

- Presentation to the participants of a small sample of social media messages from public and private organizations (institutions, companies, government bodies, etc.).

- Presentation to the participants of social media messages from national public administration institutions.

- Knowledge of and opinions on Transparency Law.

- Perceptions of the link between transparency and digital social media use by institutions.

The sample of tweets used during the discussion group (stimuli) was based on a search of more than 150 accounts of different national public administration institutions, divided between Facebook (57 accounts) and Twitter (90 accounts). The qualitative analysis software Ncapture and NVivo were used to capture the data (social media posts). In total almost 40,000 posts were collected between February 1 and March 21 2017, each purposefully selected on the basis of the diversity of message content and aesthetics. The end result of this process was the construction of a body of 67 stimuli posts from different organizations, representing the broadest variety possible.

3. Disclosure and Sharing of Information on Social Media

The legitimating function of information transparency in democratic societies has already been mentioned above. Numerous studies have examined new information technologies and the potential they offer to citizens by facilitating interaction between State institutions and civil society (Subirats, 2012; Villoria & Ramírez, 2013). Along similar lines, other studies have focused on the emergence and development of the concept of Electronic Government (Gil-García & Catarrivas, 2017; Layne & Lee, 2001; Backus, 2002) as a means to access public information and encourage citizen participation in democracy. Nevertheless, in terms of transparency and effective dissemination of information, the development of new technologies is not as decisive as the communicative act itself.

Below, we examine in what sense access to information simultaneously manifests an information restriction in the discussion groups, as well as the determinants that cause this restriction from a communicative point of view. To this end, it is necessary to take into account that the objective of transparency, as a democratic ideal, is to share all information (public or private) that concerns the functioning of the whole democratic system, in particular its institutions and organisms. Nevertheless, in reality, the sharing of any information is partial or limited because it comprises the rights of others (individuals, groups, institution and organisms) to not disclose certain information, for whatever the reason. It means disclosing information that is normally considered private in a broad sense, but which in other circumstances could be inappropriate or not pertinent for reasons of courtesy, prudence, to avoid confrontation or conflict, information overload, etc.

Hence, just as Simmelian theory suggests, in terms of transparency, all information is doubly limited or restricted at a communicative level:

- Through the social differences that are produced between groups and individuals when sharing (transmission) information, based on access and the extent of dissemination. In other words, public or private strategies that are underscored by the relatively low economic cost of transparency, especially when reduced to simple dissemination of information (Kaufman & Siegelbaum, 1997; Hellman & Kaufman, 2001).

- By disclosure of information that violates the norms of coexistence and that requires the safeguarding or exclusion of certain information to sustain the relationship and the very communication on which it is based.

Taking these assumptions into account in the design of the discussion groups, and with the aim of obtaining spontaneous responses on information transparency on social media, a wide selection of tweets, from different government organizations, were randomly selected in order to observe the reception of the information in terms of perceptions and evaluations. The aim of the selection was to encapsulate the greatest variety of messages in terms of the diverse content and styles employed by the different institutions analyzed. To avoid inter-stimulus influences, the selection of posts was shown to each group in distinct order.

In each of the groups, spontaneous responses to the selection of tweets were very limited and similar. In relation to how interesting the information provided in the tweets was, most of the participants stated that they hardly followed the institutions included, be they private or public. Nevertheless, in spite of the scant amount of spontaneous contributions, some notable exceptions were evident, such as following local public administration, in particular the local authorities where the participants lived, the Spanish National Police and the Directorate-General for Traffic.

On the other hand, the general attitude to the tweets presented during the discussion groups was positive, in spite of a lack of trust towards some of the entities, especially banking and finance companies. In addition, the dynamic of the groups compensated for the relative scarcity of information in the tweets and a tendency to avoid controversial topics such as corruption, policing, law, etc. Although the limited amount of information in each tweet could be considered a priori as a lack of transparency for reasons such as the use of public funds, the interests of the powerful, or absence of fair or just procedures, etc., in general the groups coalesced around the idea that “one thing is what they tell you and another is what you think.” This points to an implicit or presupposed dimension that affects the information contained in the tweets and the understanding of transparency as conceptualized in this study: reception completes and transforms the message.

Taking this into account, the tweets and the information they contain were not given much importance except in the sense that they provoked ironic comments or the discussion of related topics that complemented or qualified the discussion. In keeping with this pattern, the groups’ responses permitted a categorization of the tweets into three types of transparency and the visibility of their informational content: ‘predictable’, ‘visible’ and ‘invisible’.

3.1. Predictable tweets

This category included tweets from public organizations such as the Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Economy, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, National Library, etc. The tweets presented in Figures 1 and 2 are examples of ‘predictable’ tweets:

Figure 1. Screen capture of the Twitter profile of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs @twitterhandle See this week’s vacancies to get a #job in #internationalorganization! Website link [VACANCIES IN INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS] Retweets 28 Likes 21 |

Source: https://twitter.com/MAECgob

Figure 2. Screen capture of the Twitter profile of the Ministry of Culture and Sport

|

MECO Culture @Twitterhandle Free bookbinding workshops organised by the #NationalLibrary of Spain in May and June. Website link Retweets 17 Likes 11 |

Source: https://twitter.com/culturagob

For the study participants, these tweets were mostly interesting because they thought the information they transmitted was useful. Emblematic tweets included those from the Ministry of Education on scholarships; job offers from the Ministry for Public Administration; traffic and travel updates from the General-Directorate for Traffic; advice and warnings from the National Police and Civil Guard; and National Lottery results; amongst others.

The discussion around this type of tweet centered on the relevance and accessibility of the information and the public interest in its dissemination. Based on these qualities and the values attributed, these tweets were thought to be more transparent than other tweets that were seen as less useful or interesting. This type of tweet is issued with certain frequency or periodicity by government agencies and is often programmed as part of marketing and communication campaigns. They are often aimed at engaging specific users and are pre-emptive rather than reactive to demands, such as requests for information by citizens. As such, messages commonly focus on encouraging citizens to behavior appropriately when interacting with institutions’ services, for example, by providing information on how to submit a particular application or complete a certain procedure.

3.2. Visible tweets

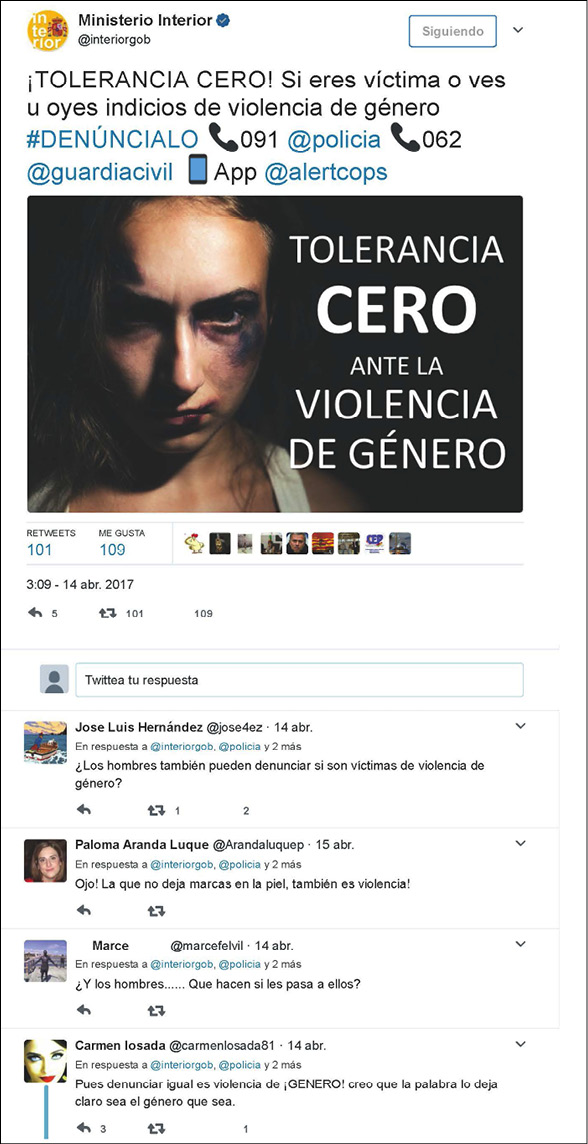

This category included newsworthy and informational tweets from organizations such as the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Development. Examples of ‘visible’ tweets are presented in Figure 3 (Ministry of the Interior) and Figure 4 (Ministry of Defense).

Figure 3. Screen capture of the Twitter profile of the Ministry of the Interior

|

Ministry of the Interior @Twitterhandle ZERO TOLERANCE! If you are a victim or you see or hear signs of gender-based violence #REPORTIT 999 @POLICE 062 @civilguard App @alertcops [ZERO TOLERANCE OF GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE] Retweets 101 Likes 109 Twitter User 1 – 14 Apr. In response to @userx @usery and 2 more Can men also report it if they are victims of gender-based violence? Twitter User 2 – 15 Apr. In response to @userx @usery and 2 more Careful! Violence can also be things that do not leave signs on skin! Twitter User 3 – 14. Apr. In response to @userx @usery and 2 more And the men…… What happens when it happens to them? Twitter User 4 – 14. Apr. In response to @userx @usery and 2 more Well report it just the same its GENDER-BASED! Violence I think the wording makes it clear whatever the gender |

Source: https://twitter.com/interiorgob

Figure 4. Screen capture of the Twitter profile of the Ministry of Defense

|

Ministry of Defense @Twitterhandle .@mdcospedal in the meeting of Defense ministers in #Malta: Spain contributes with 772 military personnel across six #EU operations Retweets 68 Likes 74 Twitter User 1 – 27 Apr. In response to @userx @usery Of whom, most will be thrown out at 45 years old because of an absurd law Twitter User 2 – 27 Apr. Its a contract that when you start you don’t know when it will finish and look there were no options…and I’m telling you. My relative studied and [they became a] sergeant. Others GC [Guardia Civil]. |

Source: https://twitter.com/Defensagob

In relation to this category of tweets, the study participants’ responses tended to revolve around an appraisal of the information offered, either by criticizing it or remarking (sometimes ironically) on the source of the information, the issues addressed, and how the messages tended to be received by citizens. Thus, even though the participants did not find the content of the tweets particularly relevant or practical, it was notable that they provoked a relatively strong interest. By observing the responses to the tweets, it is also possible to observe the ease with which this interest acted to stimulate the propagation of messages amongst users. In this respect, they functioned as mechanisms of emotional discharge and consequently, from a receiver perspective, as a means of channeling new information, which may be implicit or hidden. As such, even though the information contained in the tweets was not considered to add anything new, neither do they lack transparency as they become entangled in the information provided by the participants themselves when they offer their opinions and contribute to their dissemination.

As such, visible tweets fundamentally promote collaboration and implication of citizens in the institutional values they aim to represent and are well complemented by social media activity. In terms of collaboration, they are based on information that is relevant to people’s day-to-day lives, such as reminding them of safety measures, providing safety alerts, or compliance with institutional obligations. This respect, the tweets disseminate information or desirable attitudes in relation to issues that have high public awareness, such as the fight against gender violence, opposition to animal mistreatment, and reinforcing values of respect for specific groups of people, etc.

Invisible tweets

Finally, we find a group of tweets that, according to the study participants, “do not contribute anything.” These ‘invisible’ tweets do not arouse any interest and go completely unnoticed, examples being those from the Ministry of Defense (Figure 5) and the Ministry of the Economy (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Screen capture of the Twitter profile of the Ministry of Defense

|

Ministry of Defense @Twitterhandle #SundayReading Three centuries training sailors @Armada_esp #300GMMA Website link Retweets 68 Likes 74 |

Source: https://twitter.com/Defensagob

Figure 6. Screen capture of the Twitter profile of the Ministry of the Economy

|

Ministry of the Economy @Twitterhandle Inflation decreases to 2.3% due to changes in the price of energy Website link Retweets 21 Likes 22 |

Source: https://twitter.com/_minecogob

The information contained in these tweets is classed as ‘institutional advertising’ that has low or zero interest for the participants. On occasions they were compared to leaflets or propaganda whose only purpose was to promote particular events such as the inauguration of public works or the routine activity of the ministry, etc. On the basis of a lack of intentionality in the information provided, the participants tended to ignore or denigrate the tweets, deeming such lack of effectiveness to be a reason to doubt their transparency.

In general, the disaffection expressed towards this type of tweet is linked to the dissemination of information about the institution and its function for citizens. One of the frequent uses of such tweets is to respond to citizens’ questions on institutional services or, to a greater extent, to redirect users to appropriate departments. From a more strictly communicative perspective, there is a dominance of a phatic linguistic function that manifests the existence of a permanently open line of communication between institutions and citizens. However, the messages emitted from the institution tend to use a lexicon that is considered bland, depersonalized, cold and therefore also emotionless. In other words, characterized by bureaucratic distance and dominated by promotional aims or basic information.

In short, for the study participants, these three categories establish identifying forms that classify tweets on the basis of overall responses and how much the information transmitted discloses. In the following section, the analysis focuses on the incidence of these categories in relation to different types of reception transparency.

4. Types of Information Transparency on Social Media

On the basis of the categorization of tweets and an analysis of the importance of information disclosure and level of sharing, it was possible to identify four types of reception transparency: promotional, expositive, transmission and credible.

4.1. Promotional transparency

The first type of transparency relates to the disclosure of information by the sender. It relates to ‘promotional’ transparency focused on the dissemination of information whose value is limited and even considered disreputable by the receiver.8 The groups discussed how government institutions appear to be interested in promoting and disseminating certain information regardless of its relevance, interest or demand amongst users. In this respect, such information is understood to be official but only responding to the interest of the sender. Hence, tweets classed as ‘invisible’ are also identified as ‘promotional’, and little more. However, by ignoring the interests of the receiver and their labeling as distant, neutral and institutionally oriented, they also raised suspicions that they may be concealing information. Comments attributable to this type of transparency are of the following type:

P39: It’s, it’s a bit like just, a bit like the weather [forecast], isn’t it?

P1: Yes, it’s a bit of a fricada [meaning something unusual, surreal, or eccentric].

P3: ‘Here we bring you the ‘photo of the day’ by Robert Jones from Barcelona’, what do I know [laughs].

(RG1)

4.2. Expositive transparency

Linked to receivers’ uncertain interest and especially the absence of sender intentionality, the analysis identified an ‘expositive’ transparency that makes certain information known but which lacks any particular will to actively disseminate it. This is information that is just “thrown up” on platforms, such as information that is posted on a website, a forum or in an official bulletin. Without any accompanying efforts to transmit it to a broad audience, receivers may interpret its expositive transparency as a lack of interest in communicating. See the following extract:

P1: They should post messages like: ‘for Christmas, a gift of €100 for everyone!’, that’s what they should post.

P2: Exactly [laughs]

P1: That’d be wonderful.

M: But, for example, a message like this…

P2: No, let’s see …

M: that says: ‘Direct sale of goods/assets, property of AGE, located in Loeches, Madrid.’ A message like that…

P3: No.

(RG2)

4.3. Transmission transparency

In turn, the same effort at dissemination allows us to speak of a ‘transmission’ transparency characterized by a form of dissemination that gives importance to the relevance and content to the information disclosed. In other words, the information is disseminated because it is of interest (real or supposed) to the receiver and not just the sender. The inclusion of the receiver and by consequence the existence of this supposed receptivity presupposes the incorporation of a ‘receiver transparency’, which leads to the expansion (propagation) of information disclosed in terms of reach and meaning. ‘Visible’ tweets are partially identified with this type of sender transparency, which centers on the dissemination of information thought to useful. Emergencies, alerts and warnings are examples of information that is considered relevant to citizens in general, as well as guaranteeing its further propagation amongst individuals and therefore its effectiveness:

P1: because a lot of the time they post a screenshot of a webpage or an email so that you can recognize it. I think that type of think is good because it complements the information. I mean, the ministry, or whatever, ‘the National Police warns of a new scam that tries to get your account number through such and such an email.’ So they give you a screenshot of the email, which is stamped with ‘beware’ or whatever […] so that you can recognize it [if you get one]. I think that type of thing is complementary and necessary.

(RG1)

4.4. Credible transparency

Finally, we find a type of transparency that is affected by the limitations or incongruences of disclosure (emission), but not by the dissemination that is a consequence of said shortcomings. This type of transparency incorporates both the act of seeing and looking. In this case, what is really disseminated and shared are the interpretations and suspicions of the receivers in relation to what is not disclosed by the sender.10 In visual terms, this transparency offers information that the receiver judges to be unexpected and “attention grabbing” from a more complete or coherent perspective. Although the purpose of the disclosure is transparency, this defective willingness to disclose generates a type of special informational knowledge that has two functions.

Firstly, the imaginative completion partial or restricted disclosures that the receivers find unsettling or intriguing and therefore demand further information. Amongst the study participants, this informational deficit was rapidly completed through the projection of assumptions or suspicions, whose veracity is ancillary. Secondly, it moves disclosure beyond the operation of transparency itself to the subject that has demanded it (the receiver). Paradoxically, the citizen (user) makes the effort to produce the transparency, in the sense that said transparency is limited or lacks coherence from their point of view.

As a counterpoint to the absence of voluntary disclosure (or defective disclosure from the perspective of the sender) a type of ‘credible’ transparency is produced that that informs through interactive communication media and through the users that demand certain information. This transparency therefore goes beyond the reach of the simple act of disclosure and, as such, of the control of the sender. The following extract demonstrates the double condition that information transparency acquires when it generates disquiet and intrigue on reception:

M: This one is also from the Ministry of Development. What do you think about this one? The one that says ‘Spectacular view…’ What do you think about a ministry publishing or sending out this tweet or this message? ‘Spectacular view of this lighthouse, [#]on the way, [#]Easter. Where is it?’

P1: There are lots of that type of photo, not just from the Ministry of Development, from other travel pages and things that say ‘look at this place’ and you see an amazing photo.

P2: [laughs] You see? The comments, the comments.

P1: The comments are the best part.

P2: Absolutely, absolutely.

P4: In Switzerland [laughs]

P2: It’s really good, it’s brilliant, that comment. They ask for it, it’s because…, they ask for it.

(RG3)

Effectively, ‘visible’ tweets are those that give greater credible transparency to transmitted information, in the sense that they generate controversy and awareness on social media through popularity or by becoming a ‘trending topic’.

Apart from this final type of transparency, and from a theoretical point of view, it is known that the disclosure of any information produces, by defect, undisclosed information and the corresponding projection (imagined) that attempts to fill this information gap. It’s a game that has no end, one that foments the same communicative act as a result of transparency, creating at the same time a new social link and desire for more information and knowledge.

Credible transparency is, as such, a form of information dissemination that relies on the self same communicative act to encourage propagation by not fully complying with the information desired (and to a degree communicated). If the communicated information includes a meaning that appears to be out of place, the receiver is obliged to create a (metaphoric) meaning or assume a double meaning in order to complete the desired information. Suddenly, all information emitted by the sender may be viewed as containing hidden or inadvertent meaning that the receiver must interpret.

On the other hand, the very potential of social media is considered ambivalent and limited. They are positively viewed as instruments for limitless sharing and contacting with others, but also negatively in terms of disclosure and lack of control and monitoring of shared information. For this reason the study participants repeatedly commented that uncontrolled disclosure is even greater than suspected. In this respect, while using social media, they sometimes use practices to protect themselves or just accept this type of disclosure as the price to pay for its use.

In any case, it seems evident from the analysis that social media are understood as a medium that is consistent with the phenomenon of transparency as it more than complies with the objective of disclosure and dissemination of information. On the one hand, they make social relations in shared communication possible and encourage them without restrictions. On the other hand, they provide select information that aims to activate and replicate the expansion and limitless propagation of said information.

5. Conclusions

This article presents the results of an exploratory study on institutional information transparency on social media with the aim of exploring its communicative reach and citizen participation in political life. Based on the analysis of the discussion groups, a number of important conclusions can be made.

Firstly, the analysis makes clear that the reception of information is a separate and independent part of the communicative process to its emission and the sender. This distinction affects and goes beyond the narrow conception of a formulation of transparency limited by standards and procedures unilaterally defined by the sender.

Secondly, on the basis of reception transparency, the generic idea that associates information accessibility with effective transparency is at the very least dubious. The research finds that accessibility is in no way sufficient, in and of itself, to justify any claims of transparency. Furthermore, it is clear that the provision of ‘free’ information can also equate to a lack of transparency, as shown in the case of communications that generate no awareness or are of no interest to receivers.

Thirdly, of the four types of transparency identified in the analysis of the groups (promotional, expositive, transmission and credible), credible transparency demands a greater requirement of information from the issuer due to the importance of the limited information disclosed to the receiver. In other words, in essence, it is the receiver who completes and reveals information beyond that provided by the sender. In a way, this modulates (and compensates) the supposed informational capacity of citizens on interactive communication media, like social media. In any case, future studies will need to examine, in comparative terms, the functioning and scope of credible transparency.11

Table 1. Types of information transparency according to the source of emission and reception

|

Types of information transparency Yes |

Information provision by the receiver |

||

|

No |

|||

|

Information provision by the sender |

Yes |

Transmission |

Promotional |

|

No |

Credible |

Expositive |

|

Source: Author’s own elaboration

While keeping in mind the typology presented in this study, it is necessary recognize that studies on the United States’ Open Government Initiative have highlighted the confusion that exists between perception of transparency and the use of social media (Unsworth & Townes, 2012). Furthermore, most studies demand greater governance of social media by those public institutions more closely involved in promoting citizen participation and interactivity with government and which are usually more transparent themselves. Presently, this only seems to occur in those public agencies and organizations that are directly involved with the implementation of transparency programs (Bekkers, Edwards & Kool, 2013).

In the case of Spain, one of the backbones of the Transparency, Access to Information and Good Governance Act (19/2013) is an obligation to publish under two criteria. Firstly, to make information on the work of the government public (by publishing or providing access), and secondly, to make such information accessible and available to the fullest extent possible. With particular reference to the criteria of accessibility, the high penetration and usage rates of social media amongst citizens mean that it has an important role to play in the production of information transparency.

6. Acknowledgements

Thank you to Paul R. Cassidy for the Spanish-to-English translation.