1. Introduction

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), plagiarism is the “act of offering or presenting as one’s own the work of another, wholly or partly, in a more or less altered form or context” (WIPO, 1980: 192). Research carried out on plagiarism provides their own definitions, such as introducing it as “the ideal seizure of all or some elements originally contained in the work of another author presenting them as one’s own” 1 (Lipszyc, 1994: 19), “the misappropriation of the creation of another” (González Gómez, 1998: 192) or “the intention to pass the ideas, research, theories or words of others as one’s own” (Moss, 2008: 23). Some authors go further and refer to the right of paternity of creations, by considering that plagiarism is the “total or partial appropriation of original elements of another person’s work, in identical or simulated form, with usurpation of the paternity of the true author to make them pass as one’s own” (Antequera, 2012: 86).

Bearing the above-quoted ideas in mind, it can be understood that a person commits plagiarism when copying, imitating, reproducing or transforming any part or the whole of an artistic or intellectual creation, without quoting the sources from which it comes or posing as its original author. Plagiarism has become a common practice and, at the same time, research into it has increased. In the academic field, for example, plagiarism represents an increasingly recurrent practice, on which many studies have been carried out. Among other topics, they have addressed the general principles that the academic work must follow (Toller, 2011), the classification of different types of plagiarism detected (Soto Rodríguez, 2012) or the analysis of the prevalence of these practices (Comas Forgas et al., 2012).

Research on plagiarism has also been found in other areas, which provides some reflection on the copyright or the protection of the author’s work in the literary setting (Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, 2010), the musical one (Grilo Bartolomé, 2017) or the fashion context (Izquierdo Dones, 2019). This topic has also been studied in the advertising field, through different works that address the protection of advertising creations. Some of them bring to light the underlying limitations of specific regulations, such as the Ley General de la Publicidad (Vázquez Gestal, 2002) or the Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (Portero Lameiro, 2017), while other research is focused on reviewing the defence against plagiarism offered by the current legislation (Tato Plaza, 2017). However, none of the aforementioned publications deal with certain assumptions, such as that of exploiting the prestige of others or imitating it, which sensibly affect the legal protection of the advertising products, on which this research is oriented. In fact, the big companies invest a significant part of their budgets in the design and research of their brands and products, but also in the way of presenting them to consumers, through campaigns and other advertising resources. In this context, creativity is an essential factor in achieving success and it requires a remarkable financial endowment to develop the different elements involved. Hence, the copy or imitation of the resulting advertising products would cause serious damage to the companies and the creativity professionals involved, due to the seizure of their studies and investments by other people, as well as for the depreciation of the originality of their proposals on the target audience.

The brand concept has undergone a great evolution over time. Currently the Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas (OEPM) defines it as a distinctive sign whose “function is to differentiate and individualise in the market some products or services from other identical or similar products or services, as well as to identify their business origin and, in certain way, to be an indicator of quality and a means of sales promotion” (OEPM, 2018). For some authors, it is more than an identifier of the product that allows its differentiation from the rest, since they consider that it represents the philosophy and organisation of the Company itself and makes it a guarantee of quality for the consumer (Pettis, 1995). In this sense, the creation of a solid brand implies clear benefits for its owner, such as that the sign itself becomes an advantage over the competing companies and that it represents an impediment to the inclusion of similar products in the market. This brand value also allows the consumer not only to focus on the price, when choosing a product or service, but also to value the sign as one more factor in the purchase decision. When dealing with trade mark, it is important to bear in mind that current legislation, both national (Ley de Marcas) and European (Regulation on the European Union Trade Mark), differentiates between denominative marks (words or groups of words) and graphic trade marks (images, symbols, figures, etc.), and the offence may affect only one of them or both.

The intention of consumers, in addition to the product itself or its brand, can be influenced by other aspects, such as labelling or packaging, which inform of the benefits and characteristics of the product and can condition the purchase. Packaging “is the set of visual elements that allows the product to be presented to the potential buyer, under the most attractive appearance possible, transmitting its brand values and its market positioning” (Unilever, 2002: 6). Therefore, the design acquires a lot of value, since “the graphic image of a product gets importance in the product packaging, which becomes the ‘silent seller’ seeking to convince that it is a product that the consumer needs” (Pérez Espinoza, 2012: 11). Regarding labelling, it can be seen as “an integral part of packaging and it usually identifies the product or brand, who made it, where and when it was made, how it should be used, and the content and ingredients of the package” (Kerin et al., 2009: 299). Furthermore, for some authors it represents “the last opportunity that the Company has to influence buyers before they make the purchase decision” (Lamb et al., 2011: 355).

In summary, both the brand (the main asset of any company) and the design of the packaging or labelling acquire essential importance in the current advertising, thus becoming aspects that must necessarily be protected. The registration of these elements is a good measure against plagiarism, although not infallible. In this sense, a series of steps have been taken at the legislative level in order to shield an original work from possible imitations and fraudulent uses. In fact, one of the aims of this research is to present the laws that can be used currently in Spain in the judicial processes for protection against plagiarism. In this regard, it should be noted that the legal protection of creations is not obtained exclusively by filing a lawsuit, since sometimes the legislation allows the affected people to avoid this route, although in many cases it is necessary to proceed in this way. Therefore, to complement this study, an empirical research was carried out on the lawsuits filed in Spain for alleged plagiarism of advertising products, which were judicially active in the biennium 2016-2017. For this purpose and following the criteria that will be detailed in section 3, a search system was designed to locate those cases that started or continued their processing in the indicated period, on which the following variables were analysed: the alleged plagiarised aspects, the legislation infringed according to the processing bodies and the sense of the final resolution, in order to determine towards which of the involved parties (claimant or respondent) the resolution was negative. Likewise, it was interesting to know the perspective of the plaintiffs about the rules that should be applied and, particularly, their level of agreement in this regard with the vision of the judicial bodies, so that this last variable was also analysed in the current research. In this sense, it is important to bear in mind that the inadequate selection of the laws on which an alleged plagiarism is based, together with an incorrect argumentation or an incomplete collection of evidences, among other factors, can lead the claimants to a certain vulnerability against this type of infringement.

2. Legislation applicable in Spain against plagiarism of advertising products

For a long time in history, plagiarism was not considered a legislative infraction, although it was rejected in some way by society. However, the fact that the plagiarist was only punished with opprobrium, greatly slowed down the appearance of legislation focused on this offence, since the seriousness of such infringement was not sufficiently assessed (Perromat Augustin, 2010: 45). In this sense, it was necessary to wait until the appearance of the Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (Ley de 10 de enero de 1879 de Propiedad Intelectual) to begin to have a legal framework that would grant protection to the authors’ rights and creations. After this law, other regulations were enacted, which expanded the range of options to exercise legal actions against plagiarism (Ley de Marcas, Ley de Competencia Desleal, Ley General de Publicidad, etc.), applicable to the advertising context. In this sense, it is important to bear in mind that plagiarism of advertising products can be derived from the copy or imitation of the advertisements, the brochures, the catalogues, the general scheme, the text, the trade marks or distinctive signs, the images, the music, the design or the packaging, among other aspects. The plagiarism of one or more of these elements is exactly the key to knowing which rule is being infringed. Thus, for example, if a trade mark or distinctive signs of a company are copied, surely the Ley de Marcas is the regulation to be invoked, but if the infringement is carried out to create confusion or take advantage of the reputation of others, probably the Ley de Competencia Desleal must also be invoked.

A good way to prevent this infringement is to register the advertising elements that one wants to protect at the Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas (OEPM), although it is not infallible either. The registration does not avoid an illicit copy of an advertising product being made. However, if the creator is aware of the infringement and his/her advertising was registered, he/she may resort in the first instance to the aforementioned body to proceed through administrative channels, whose resolution, in any case, can be appealed. Another option would be to invoke the arbitration so as to reach an agreement between the involved parties (which would mean not being able to take other types of legal actions until the resolution is obtained). Nevertheless, if the result of the arbitration or the administrative appeal is not satisfactory for the interested party, civil or criminal actions may be exercised against anyone who has infringed his/her rights and measures can be requested to protect them (art. 52, Ley 20/2003, de 7 de julio). Then, the main laws and regulations that can be used to process a plagiarism infraction are:

- The Código Penal.

- The Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (LPI, Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual), which includes the Ley de Propiedad Industrial (PI), which in turn contains the Ley de Marcas (LM).

- The Regulation on the European Union Trade Mark (RMUE).

- The Ley de Protección Jurídica del Diseño Industrial (LPJDI).

- The Ley General de la Publicidad (LGP).

- The Ley de Competencia Desleal (LCD).

- The Ley de Servicios de la Sociedad de la Información y el Comercio Electrónico (LSSI).

Despite the large number of laws indicated above, in “our legal system there is no precise and unambiguous legal concept of plagiarism that allows establishing the limits of its legal notion” (Manrique, 2013: 65). In this regard, the Código Penal (Ley Orgánica 1/2015, de 30 de marzo) is the only regulation that makes reference to the term itself and presents it as an infringement, which may lead to a prison sentence2. Subsequent articles of the Código Penal broaden this assumption, although in no case is a definition of plagiarism provided.

The first law to face the offence of plagiarism, and perhaps the most used one against this infraction, is the Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (LPI). This law establishes that “the intellectual property of a work belongs to the author through the simple fact of its creation” (Real Decreto Legislativo 1/1996, de 12 de abril), as a part of his/her personal and patrimonial rights that, in addition, allows this person to make use of his/her work legally. However, article 6 of the same law states that the author will be the one who appears in the creation with his/her signature, name or any other sign that identifies him/her. This could give rise to a certain contradiction, since this regulation affirms that the intellectual property belongs to the author who creates the work, although if it is not identified with his/her name, signature or sign, it would be difficult to prove its authorship.

Regarding the guardianship, the Ley de Propiedad Intelectual protects “all original literary, artistic or scientific creations expressed by any means or format, tangible or intangible, currently known or that will be invented in the future” (Real Decreto Legislativo 1/1996, de 12 de abril). On the other hand, the description of the type of work that can benefit from its protection does not include, at any time or category, advertising creations or products. Despite it, this law will be applied to the plagiarism infringement when it comes from copying elements, such as the trade mark or distinctive signs, through the Propiedad Industrial in general, and the Ley de Marcas, in particular. Likewise, a creation may also receive the protection of this law when the advertising product can fit into one of the assumptions included in the LPI, (for example, if someone has used a registered photograph or the name of a known person in advertising on an illicit way, or if the terms of an assignment or exploitation contract have been exceeded).

In order to demonstrate that there is plagiarism of the trade mark or distinctive signs, a series of requirements will have to be achieved that are not only focused on the similarity between the original and the copy. In this regard, the LM establishes a series of absolute prohibitions, according to which the trade mark cannot not be registered, nor receive the protection of this law, in the following cases:

- Signs that are not capable of graphic representation and that do not aim to distinguish the products of one company from those of others within the market (that is, that do not comply with article 4.1 of Ley 17/2001, de 7 de diciembre).

- Signs that are not distinctive.

- The denominations formed only with signs or indications that serve to designate species, qualities, quantities, destinations, value, etc., of the products or services in the market.

- Names formed only using signs or indications that have become of common use in common language to designate products or services.

- Signs made up from the nature of the product or its shape to achieve a technical result.

- Those that may mislead the consumer about the quality, geographical origin or nature of the product or service.

- Alcoholic beverages that include false geographical indications, even if the real origin of the product is indicated or is accompanied by names, such as type, style, class, etc.

Likewise, article 6 of this law introduces various relative prohibitions and, based on them, the following ones may not be registered as trade marks:

- Signs identical to a previous trade mark that designate identical products or services.

- Signs for which there is a risk of confusion, because they are similar to an earlier trade mark or because the products or services that they designate are similar.

It is important to note that the Oficina Española de Patentes y Marcas may also register a trade mark at the European Union level, if the owner of the sign wants to get protection in all member countries. This system will be governed by the Ley de Marcas or, otherwise and without prejudice to what the latter stipulates, by the Regulation EU 2017/1001 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 14 June (RMUE), which replaces the previous Regulation EC 207/2009 (RMC). The RMUE also promoted the creation of a specific legal protection office for the community trade mark law, called the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO).

An additional factor in protecting the brand against plagiarism, according to the LM, could be its notoriety or renown. Thus, article 8 prohibits the registration of distinctive signs similar to other Spanish signs that were widely known in the market sector to which their products or services were destined (notorious) or that were known to the general public (renowned). Anyway, with the latest reform of the LM (Real Decreto Ley 23/2018, de 21 de diciembre3), the distinction between these two types of trade marks disappears, being designated in both cases as renowned and including the trade marks of any state of the European Union. Another novelty that the aforementioned reform introduced was the extension of the registration prohibition of those signs that imitate the shape or other characteristics of the existing ones.

Regarding the infringements of industrial designs, the LPI will deal with them, although these may also be regulated by the Ley 20/2003 de 7 de Julio, de Protección Jurídica del Diseño Industrial (LPJDI, Ley 20/2003, de 7 de julio). This law, which arises from the obligation of adapting to the community regulations and providing the design with an industrial protection according to its current needs, as the aforementioned law, does not grant its protection to the product itself, but rather it protects “the value that the design adds to the product from the commercial point of view, regardless of its aesthetic or artistic level and its originality” (Ley 20/2003, de 7 de julio). This duplicity in the protection of industrial designs reaffirms the idea that there is no specific legislation that deals with plagiarism infringements and, even less, with plagiarism of advertising products. On the other hand, the LPI is also applicable to cases of copyright infringement (moral rights or economic rights), for which it will be taken into account if there are transfer rights and if these have been transgressed in any way.

Focusing on the specific legislation on advertising and communication, the current regulation leads us to the Ley 34/1988, de 11 de noviembre, General de Publicidad (LGP), and the Ley 3/1991, de 10 de enero, de Competencia Desleal (LCD), both intended to regulate the advertising activity and to repress the infractions in this area. These two laws represent channels parallel to the LPI, giving answer to infringements of advertising plagiarism that do not find the appropriate protection in the latter. In addition, both laws are interrelated so that, in some cases of illicit advertising, the first of them will lead us to the second one.

The LGP has been the law of reference in this subject, despite the subsequent appearance of the LCD. The latter is responsible for regulating cases such as misleading advertising, comparative advertising or unfair advertising, in addition to collecting a series of actions for unfair competition parallel to the actions for illicit advertising established in the LGP.

This scenario made it necessary to pass the Ley 29/2009, de 30 de diciembre, which modifies the legal regime of unfair competition and advertising in order to improve the protection of consumers and users. Then, title IV of the LGP on cessation, rectification and actions is completely abrogated, at the same time that the duplication of some cases is eliminated. Through this reform, the law maintains the types of illegal advertising in its article 3, but only develops those that the LCD does not include (subliminal advertising, advertising that infringes the dignity of the person, etc.). Thus, some assumptions of illegal advertising such as unfair advertising, misleading advertising or comparative advertising, are only included in the second law.

Another reason that led to the reform of the Ley General de la Publicidad and its promulgation was the need to adapt two community regulations to the Spanish legal regime: the Directive on misleading advertising and comparative advertising (Directive EU 2015/2436 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 16 December) and the Directive on unfair commercial practices in their relations with consumers (Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 11 May). This meant that the new law incorporated a clear and general definition of the concept of advertising, presenting it as “any way of communication carried out by natural or legal person, public or private, in the exercise of a commercial, industrial, artisan or professional activity, in order to directly or indirectly promote the contracting of personal properties or real states, services, rights and obligations” (Ley 34/1988, de 11 de noviembre). Regarding the protection of advertising, the LGP confers the protection of advertising creations both on this law and on Ley de Competencia Desleal, as well as on other special rules that regulate specific advertising activities (art. 1, Ley 34/1988, de 11 de noviembre). Here we can check once more how these two laws are interrelated and one leads to the other.

As regards plagiarism of advertising products, the fact that the LCD has included certain assumptions that, so far, were the responsibility of the LGP, means that the latter does not currently contain many articles adapted to the object of study. For this reason, in addition to the articles referring to illegal advertising, worth of note is Title III, related to advertising contracts, which will be under the protection of its articles and, if this is not possible, they will be governed by Ordinary Law.

It is important to highlight that the modifications introduced by the Ley 29/2009 in the LCD lead to the creation of a new social model that divides protection against unfair competition into two groups. Thus, to the acts of unfair competition that were already considered, addressed to protect the private interests of the companies, those that affect consumers are added. This law reform offers a very important protection related to the competition in the market, by prohibiting, as stated in article 1, acts of unfair competition, which includes illegal advertising, although this is subject to the Ley General de Publicidad. To commit an unfair practice, only two conditions must be met: to be carried out in the market (that is, external) and done for concurrent purposes (that the act aims at promoting and affirming the diffusion in the market of own or third party products).

The acts of confusion, included in article 6, make reference to plagiarism, although in this case it is not intended to pass a creation as one’s own, but rather to confuse the consumer about the origin of its activities, by creating the subsequent risk of associating them with other people´s profits or business. It is a prohibitive rule that only takes into account the behaviour of the offender (disregarding his/her intentionality) and that presupposes disloyalty.

On the other hand, article 10, which deals with acts of comparison, is the one that refers to the imitation for the first time, by recognising as unfair practices the imitations or replicas of goods and services designated by a protected trade mark or trade name. In the same way, article 11 of the LCD includes all acts of imitation, but affirms that copying others’ benefits or business initiatives is free, except if they are under the protection of an exclusive right (copyright, industrial property right, trade marks, etc.). However, the imitation of these initiatives is considered unfair “when it may lead consumers to generate association with their benefits or when there is a misuse of others’ reputation or effort”.

For this reason, when dealing with imitation by taking advantage of the reputation of others, the law primarily refers to imitation by reproduction, which in the advertising area could be the reproduction of photographs, designs and other aspects of other people’s catalogue in one’s own. In addition, it is indicated that this use of reputation of others must be illegal or fraudulent, avoidable and without justification. On the other hand, the systematic imitation of the services and business of a competitor is also considered as an unfair practice, if this action aims at making its assertion in the market impossible and if it exceeds what would be a natural response from consumers. In this case, article 11 of this law, which refers to imitations of material creations and the characteristics of products or services, is declaratory and only considers as unfair some cases of imitation.

Another aspect included in the legislation is the adhesive or parasitic advertising, which appears as a case of illicit advertising in article 3a of the LGP and it is also considered an unfair practice due to the use of reputation of others, as reflected in article 12 of the LCD. To these two laws, the Ley de Marcas is added if the imitation of the advertising creation is about distinctive signs. Anyway, in order to know if an advertising work incurs in unfair practices, the level of similarity with the original creation will have to be verified, paying attention to the relevance and variation of the imitated elements, as well as to their notoriety (which depends directly on their distinction and diffusion) and to the differentiating elements that it presents. In this way, the more elements are copied, the greater the similarity between the two creations, but it will also take into account if the elements of supposed plagiarism were relevant in the original advertising or if the latter presented a high level of singularity.

The Ley de Competencia Desleal also includes deceptive practices, which are divided into two types: deceptive practices due to confusion for consumers and deceptive practices due to confusion. The first ones make reference to commercial practices that “create confusion, including the risk of association, with any goods or services, registered trade marks, trade names or other distinctive marks of a competitor, provided that they are likely to affect the economic behaviour of consumers and users” (art. 20, Ley 3/1991, de 10 de enero). On the other hand, deceptive practices due to confusion (art. 25, Ley 3/1991, de 10 de enero) refer to the promotion of a service similar to another that already exists in the market, so as to make consumers believe deliberately that their products or services come from the same company or professional, thus taking advantage of the prestige or reputation of others.

The Ley de Marcas and the Ley de Competencia Desleal converge in some aspects, such as those referring to the exclusive rights of the industrial property. In this sense, while the first of the regulations protects the subjective rights of an intangible asset (provided that it has been registered), the second one is aimed at the proper functioning of the market. However, and although it is not the object of this research to review the jurisprudence related to plagiarism, we will refer to a sentence that brings to light the difficulty in choosing between the LM and the LCD. Thus, the application of “[…] one or the other legislation, or both at the same time, will depend on the claim of the plaintiff and on its factual basis, as well as on the demonstration of the concurrence of the assumptions of the respective behaviours that must be given so that they can be classified as offenders according to one of them or both at the same time” (Audiencia Provincial de Córdoba, Sentencia del 14 de julio de 2017, p. 4). In this way, jurisprudence implies a certain subjectivity in assessing the application of one or another law, since this will depend on the characteristics of each case, which will have to be studied independently.

To conclude this review of the legislation, it is necessary to take into account the regulation related to commercial communications issued in electronic format, which are increasingly used to exchange information and to develop economic and commercial activities. Specifically, the Ley 34/2002, de Servicios de la Sociedad de la Información y el Comercio Electrónico (LSSI, Ley 34/2002, de 11 de julio) aims at regulating the new type of advertising through digital ways, without prejudice to the protection provided by the LGP and the LCD. Incorporated into the legislation by the Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, this regulation refers to certain legal aspects of the Information Society Services (with special attention to those related to electronic commerce), some of which are related to the copy or plagiarism of advertising products. Anyway, it is worth clarifying that this law only regards those aspects that, due to their novelty or peculiarity, fall outside the assumptions included in the remaining current regulations on advertising. Thus, its article 8, which deals with the restrictions on the provision of services and intra-community cooperation procedures, is the first to make reference to exclusive rights, by stating that if principles such as the protection of intellectual property rights are transgressed (section 1e), the judicial bodies that regulate their protection may carry out certain measures to interrupt the feature or to remove the infringing data.

The LSSI also includes an additional rule relative to domain names, which establishes the principles of the system for assigning such names under the country code relative to Spain (.es). This assignment will be made on the basis of the rules contained in the mentioned regulation and in the Plan Nacional de Nombres de Dominio de Internet (Orden ITC/1542/2005, de 19 de mayo), as well as under the rules established by the assignment authority or those contemplated in international organisations that manage the domain name system on the internet. The public business entity Red.es will be the authority in charge of registering domain names in Spain (as provided in the sixth additional provision, Ley 11/1998, de 24 de abril, General de Telecomunicaciones), but the aforementioned law establishes the obligation to respect intellectual or industrial property rights.

In summary, the Spanish legal framework offers an extensive legislation to take legal actions against alleged plagiarism infringements, particularly in the advertising area. This wide number of rules can lead to somewhat imprecise protection, since it is not always easy to discern which law is being transgressed. In fact, as already indicated above, plagiarism of a specific advertising product can respond to seven different laws, depending on its characteristics. It must be added to this that the ideas are not protected by law, but only their development, and that the concept of plagiarism is not included in any of the regulations of the legal system related to this infringement (with the exception of the Código Penal). All of it highlights the enormous difficulty involved in the proper selection and application of plagiarism legislation when dealing with this offence.

3. Material and method

To complement the study of plagiarism in advertising, a research was carried out into cases of alleged copying of advertising products in Spain, which were judicially active in the biennium 2016-2017. To obtain the sample used in this work, the indicated period of two years was selected in order to collect a significant set of data corresponding to the period after the reform accomplished in the Código Penal (Ley Orgánica 1/2015, de 30 de marzo), which introduced as a novelty the possibility of imprisonment for committing this offence. It should be noted that we considered as judicially active cases in 2016-2017 all those involved in a judicial process in any of the two indicated years.

Regarding the spatial delimitation of the study, the whole Spanish territory was chosen. In this sense, it was taken into account that, although the community regulations also apply in other states of the European Union, national legislation must be applied in each country in parallel, in those cases where it is appropriate. Consequently, with the indicated delimitation, the cases found would correspond to the same legal framework and should respond to identical infringements of the Código Penal.

The data used in the current research were obtained by observation, through different sources aiming at locating the lawsuits, judicially active in the period 2016-2017, in which plagiarism of one or more of the following elements had been reported: the distinctive signs of other advertisers, the text, the images, the slogan, the general scheme, the design, the music or sound effects, the commercial appearance and the copy or imitation of the product. The main source of information was the Centro de Documentación Judicial (CENDOJ), dependent on the Consejo General del Poder Judicial, whose database contains the data of all the processes that the different courts have dealt with over the years and their corresponding resolutions. The EUIPO database was also used, which made it possible to locate those claims that were processed through the judicial channels of the European Union. To search for the cases in both databases, different keywords were used, referred to plagiarism and other names of the offences, to the different advertising products or to the different rules and rights included in them. In addition, the press was used as a source of information and, more specifically, three media with great coverage at state level: El País, El Mundo and ABC. The motivation for the inclusion of this source was the location of several news items related to alleged plagiarism of advertising products in the indicated newspapers. However, in most of them either no legal actions were taken or it could not be proven that an infringement really existed, so they were discarded for the study. The remaining cases were incorporated into the sample only if the information on the corresponding demand could be obtained through the CENDOJ or EUIPO databases, thus obtaining only 4% of the data. The following table summarises the distribution of the cases according to the location source.

Table 1. Sources for location of cases

|

Source |

Nº of cases |

|

Only CENDOJ |

144 |

|

CENDOJ and Press |

4 |

|

EUIPO and Press |

2 |

|

Total |

150 |

Source: created by the authors

Once the sample was selected, each of the lawsuits included in it was monitored until its final resolution, to obtain information on the different variables indicated below: alleged plagiarised aspect, infringed laws according to the judicial responsible, coincidence on the infringed legislation (between the complaining party and the assigned body) and sense of the final resolution. With the resulting information, a database was prepared in Excel format, which was then analysed with the Excel and R-Commander programs to respond to the objectives set out in the research. For this purpose, quantitative exploratory methodology was used, in order to describe the information obtained for the variables under study through tables and graphs. The main results are summarised in the following section.

4. Results

The sample used in this research contains those claims for plagiarism of advertising products, which were located through various sources and they began or continued their judicial processing in the biennium 2016-2017. The table below summarises the information regarding the alleged plagiarised items.

Table 2. Alleged plagiarised aspects

|

Alleged plagiarised aspects |

Percentage of cases |

|

A01-Design |

6,6% |

|

A02-Design/Other aspects |

1,3% |

|

A03-Labelling |

0,7% |

|

A04-Labelling/Denominative and graphic brand |

0,7% |

|

A05-Labelling/Denominative brand/Other signs |

0,7% |

|

A06- Labelling/Graphic brand |

0,7% |

|

A07-Denominative brand |

65,9% |

|

A08-Denominative and graphic brand |

10,6% |

|

A09-Denominative and graphic brand/Other signs |

0,7% |

|

A10-Denominative brand/Design |

1,3% |

|

A11-Denominative brand/Other aspects |

0,7% |

|

A12-Denominative brand/Other signs |

2,7% |

|

A13-Graphic brand |

3,3% |

|

A14-Other aspects |

0,7% |

|

A15 Other signs |

0,7% |

|

A16-Packaging |

2,7% |

|

Total |

100% |

Source: created by the authors

The previous results show that the brand, either denominative or graphic, is the aspect included mostly in the plagiarism lawsuits (87.3%) and, particularly the denominative brand (83.3%), followed by far by the graphic brand (16%) or the design (9.2%). This means that almost all the cases analysed should have appealed to the Ley de Marcas or the Regulation on the European Union Trade Mark (if it were a community trade mark) for processing these infringements. However, in some of these situations more than one item (8.8%) was plagiarised, so the same case could transgress several laws at the same time.

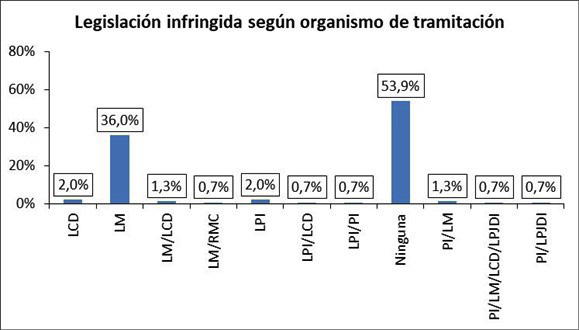

In practice, in addition to the aspects on which an offence may have been committed, it is important to also take into account the context around each particular situation, in order to establish the infringed laws. In this sense, the following graph shows the perspective of the processing bodies on the laws transgressed in the litigations included in the sample.

Figure 1: Infringed legislation according to the processing court

Source: created by the authors

As can be seen, the judicial bodies that received the claims considered that there was no infringement in more than half of them (53.9%). It should be also be noted that, according to the criteria of the judicial bodies, the most transgressed law was the Ley de Marcas (40%), followed by far by the Ley de Competencia Desleal (5.1%), the Ley de Propiedad Intelectual or the Ley de Propiedad Industrial (each infringed in 3.4% of the conflicts), and the Ley de Protección Jurídica del Diseño Industrial (1.4%). On the other hand, taking into account that both the Ley de Propiedad Industrial and the Ley de Marcas are part of the LPI and jointly accounting all these cases, it could lead us to conclude that this last law was involved in 44.1% of the lawsuits studied. In the same way, because the Ley de Marcas is included in the Ley de Propiedad Industrial, the assigned courts considered that infringements of the latter law were detected in 41.4% of the complaints.

In order to know in more detail on which laws the judicial responsible relied to issue their resolutions as regards the cases processed, Table 3 presents this information, disaggregated into the different aspects on which plagiarism lawsuits were filed.

Table 3: Infringed legislation according to the judicial bodies, for each alleged plagiarised aspect (only including those aspects with more than two cases)

|

Infringed legislation according to the judicial bodies |

Alleged plagiarised aspect |

|||||

|

A01 |

A07 |

A08 |

A12 |

A13 |

A16 |

|

|

LCD |

10,0% |

6,2% |

||||

|

LM |

42,5% |

43,8% |

25,0% |

40,0% |

25,0% |

|

|

LM/LCD |

2,0% |

|||||

|

LM/RMC |

20,0% |

|||||

|

LPI |

10,0% |

|||||

|

LPI/LCD |

1,0% |

|||||

|

LPI/PI |

10,0% |

|||||

|

None |

50% |

54,5% |

50,0% |

75,0% |

40,0% |

75,0% |

|

PI/LM |

||||||

|

PI/LM/LCD/LPJDI |

10,0% |

|||||

|

PI/LPJDI |

10,0% |

|||||

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Source: created by the authors

These results confirm that the dominant trend, in the different cases of plagiarism, was the dismissal of the claims by the processing bodies, considering that no law was infringed (the percentages range between 40% and 75% for the different aspects considered). Out of the cases in which the transgression of some legislation was observed, those that alleged plagiarism in the design were particularly noteworthy, due to the variety of laws used by the judicial bodies to issue their decisions. In the remaining situations in which an infringement was detected, the judicial responsible relied on the Ley de Marcas, as expected, because the trade mark (denominative or graphic) appears as the main object of the complaints, although they also alluded to this rule in some claim for plagiarism in the packaging (25% of these cases).

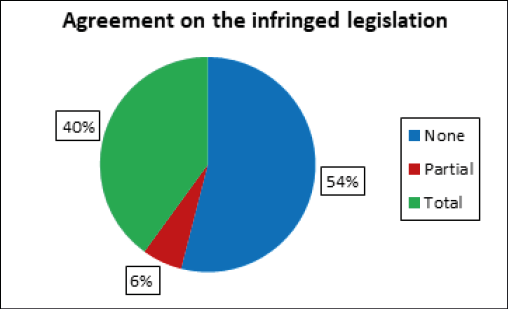

In this study, it was also interesting to analyse the view of the complaining party on the laws that they considered infringed and that were used as the basis for their claims. In this regard, a significant level of discrepancy with the perspective of the judicial bodies was observed, as can be seen from Figure 2.

Figure 2: Degree of agreement on the infringed legislation between the complainant party and the judicial processing body

Source: created by the authors

In more than half of the cases (54%), there was a total disagreement between the plaintiff and the responsible body regarding the laws that could be applied to resolve the complaints presented. In 40% of the lawsuits there was absolute agreement on the infringed legislation, while this similarity of criteria between the processing body and the complaining party was only partial in the remaining cases (6%).

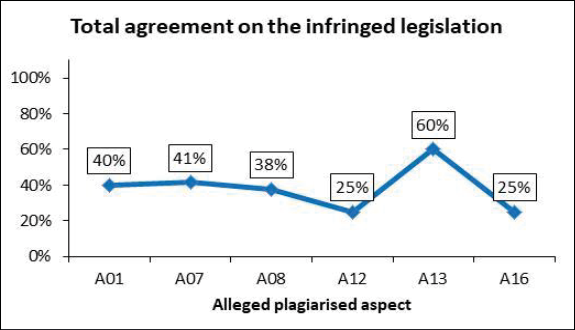

To establish whether the level of agreement was maintained in the different alleged cases, Figure 3 shows the percentage of cases in which there was total agreement on the infringed laws, for the different aspects that were considered plagiarised.

Figure 3: Percentage of total agreement on the infringed legislation for each alleged plagiarised aspect (only including those aspects with more than two cases)

Source: created by the authors

Although for some of the alleged plagiarised aspects, the pattern of total concordance that had been detected for the whole sample seems to hold, about 40%, that percentage decreases to 25% for others, as happens when the packaging is the sole element included in the suit. The single exception to this level of disagreement can be observed in the litigation that affected the graphic brand, in which both perspectives agreed on the legislation that had been transgressed in 60% of the cases.

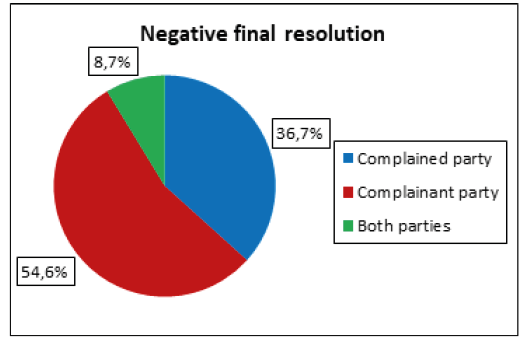

Another of the variables considered in this research was related to the sense of the final resolutions issued by the processing bodies, aiming at specifying with this variable which of the parties involved in the lawsuit (claimant and respondent) was negatively affected by the judgment handed down in the judicial process. The results obtained are summarised in the following graph.

Figure 4. Party of the claim for which the final resolution was negative

Source: created by the authors

Out of the total number of conflicts that made up this study, the complaining party was the most affected by the results of the resolutions (54.6%), while they were negative for the claimed agents in a lesser proportion (36.7%). In the remaining situations, the result of the sentences affected both parties (9%).

It should be noted that, in those cases that were negative for the complainants, their claims were rejected, which could include the receipt of some compensation, the prohibition of someone else’s use of an advertising element or resource that they considered as their own, etc. Furthermore, in those situations, the plaintiff had to bear the whole or a part of the costs and to accept that the claimed party could continue using or exploiting the alleged illegal advertising. With regard to decisions unfavourable for the defendant party, the most common consequences led to their prohibition of using and exploiting the plagiarised elements (through their withdrawal from the market, destruction, seizure, etc.), to the payment of compensation to the claimants or even to the publication of the final sentence in some media.

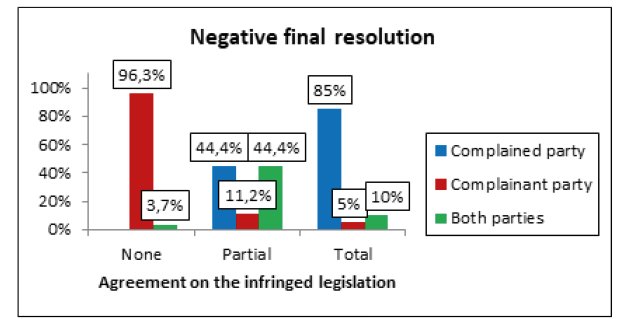

To conclude this study, Figure 5 presents the information on the sense of the final decisions issued by the judicial authorities, disaggregated according to the degree of agreement on the infringed legislation (between the responsible bodies and the claimants).

Figure 5. Party of the claim for which the final resolution was negative, according to the agreement on the infringed legislation between the complainant party and the judicial authority

Source: created by the authors

The agreement (between the responsible bodies and the claimants) on the rules to be applied resulted in negative resolutions towards the claimed party, as expected. In fact, in situations where there was full agreement, the results were mostly unfavourable for the defendants (in 85% of the litigation). When the perspectives on the infringed legislation partially coincided, the judgments that harmed the complaining party increased slightly, while the remaining negative results were equally distributed between those that affected only the defendant or both parties. This pattern changes radically in the lawsuits in which there was absolute disagreement on the laws to be applied, which were resolved contrary to the complaining party, in almost all of them (96.3%).

5. Discussion and conclusions

From the information analysed in this research, it is clear that there is no concrete definition of the concept of plagiarism and no specific rule that includes all the assumptions of this infraction. Regarding the latter, it has been shown that plagiarism claims could be processed through seven laws, which converge between them in some assumptions. Added to this is the fact that, according to jurisprudence, each case will have to be studied individually, which makes it difficult for legal representatives to properly frame the alleged infringement in the current legislation and, therefore, it may cause some defencelessness against this offence. Anyway, it should be kept in mind that the decisions reached by the assigned judicial bodies are not only based on the transgressed law, but also take into account other factors, such as the final decisions of the courts that have set a precedent.

In the advertising context, the problem is further aggravated by the lack of regulations that specifically protect the work and creations in this area. In fact, although a priori it seems that copyright could be used for this purpose, the requirements that advertising creations must meet to gain access to its protection are not regulated (Tato Plaza, 2017).

Another problem detected is that the protection of the law includes the works and creations, but not the ideas on which they are based, which adds defencelessness when it comes to advertising campaigns, since, in most cases, the idea is the centre of them. On the other hand, by considering the parameters set out in the legislation to determine if there is an infraction of plagiarism (distinctive signs, text, design, etc.), it does not seem difficult to avoid these limitations and proceed to copy a work without incurring in an illegal practice.

One of the most widely used laws in alleged plagiarised infringements is the LPI. This law states that the author has certain rights over his/her work for having created it, although the problem of trying to defend it when it is not registered highlights that it is not so easy to prove the authorship. Likewise, the fact that the work must have been published in some format to receive protection results in a total defencelessness for those creations that have not yet seen the light. Furthermore, this law provides a protection very similar to that offered by the LPJDI in the event of an infringement related to the advertising design, which makes its proper application difficult, since choosing between them can be an arduous task of interpretation and review of jurisprudence.

The LM is one of the most complete laws to process trade mark infringements, although it also requires the registration of the trade mark in order to provide its protection, with the exception of renowned trade marks. On the other hand, the LCD tried to fill the gap in the legislation regarding unfair practices, although some assumptions of this rule have led to controversy. In particular, it is worth mentioning the fact that it considers the imitation of benefits or business initiatives to be free or that the copying of a creation is lawful if there is no risk of confusion. Likewise, it differentiates between the collective interests of consumers and the private interests of companies, so that commercial practices will have to face a double legal regime. The LCD shares some assumptions with other laws, such as the LGP or the LM, so its application will require a detailed analysis of the situation, to offer an adequate protection against this infringement.

The empirical study carried out has revealed the high level of incidence of conflicts due to plagiarism, as we can see in the number of complaints collected for the present study, especially considering that they correspond to a period in which this type of infractions could already have jail sentences. On the other hand, it has become clear that the brand is the aspect most intended to be imitated and almost all the claims were focused on it. However, those situations related to infringements in the design, labelling or packaging were much less common. Bearing this in mind, it seems reasonable that the Ley de Marcas was the most frequently infringed legislation, according to the criteria of the judicial processing bodies, although it is surprising that a greater proportion rejected the claims raised by the plaintiffs, based on some of the indicated laws. In fact, the final resolutions were negative for the claimed agents in a range lower than 37%, while for the claimants they were negative in more than 54% of the cases. This shows the difficulty in proving the existence of plagiarism and that the similarity between two creations is not sufficient proof to validate the infringement. In addition, the fact of basing the claims on the most appropriate regulations is another key aspect for the judicial bodies to coincide with the perspective of the claimants and to issue decisions favourable to them. However, the collected data show that in more than half of the cases there was total disagreement on the transgressed legislation, although the lawsuits in which the graphic trade mark was the alleged plagiarised aspect were those that presented a higher percentage of agreement.

Anyway, the great discrepancy observed between the claimants and the judicial authorities highlights the difficulty in discerning the legislation that is being infringed. The existence of a large number of laws to deal with an alleged infraction of plagiarism contributes to this, with assumptions that could overlap and that would require an appropriate interpretation for their proper selection. In the case of advertising products, the problem is even greater, since there is no specific regulation for this field and the existing legislation does not fit into its particularities. However, we cannot lose perspective that the results of the judicial processes are also influenced by other variables, such as the argumentation used to present the infringement or the application that was made of the elements alleged as used illegally, which will be studied in further research.

6. Acknowledgements

This article has been edited by Karen Joan Duncan.